Spectres & Souls

The ‘centennial month’ of July 2021 highlighted many aspects of Communist Party ideology and practice that, superficially at least, seem germane to the Xi Jinping era (2012-). For those with a longer perspective, and more retentive memories, however, the underpinnings of this year’s pharaonic display of pomp and circumstance were evident (unavoidable, in fact) long before the advent of the man we think of as the Chairman of Everything.

For example, attacks on ‘historical nihilism’ — that is the questioning of the Party’s monolithic version of history, the truth and everything besides — although called by other names, were frequent enough even in the 1980s; and the miscreant Liu Xiaobo was denounced in late 1989 for contributing to the intellectual nihilism that fed the popular uprising earlier that year. Red DNA 紅色基因 hóngsè jīyīn might seem to be an inventive, Xi-era catch-phrase, but it merely encapsulates ideas and reflects practices that have been a significant feature of the lavishly funded patriotic indoctrination of China’s young people since the early 1990s. These, in turn, were part of the substantially Soviet-influenced patriotic education initiated by the Party in the early 1950s that built on over thirty years of history-as-propaganda, one of the masters of which was Mao Zedong .

Indeed, the ‘historical imaginary’ that has been so prominent in the splendiferous celebrations of the party centenary in 2021 has been cultivated, curated, manipulated and refined for nigh on ninety years. Long before Xi Jinping became the uncrowned autocrat of China’s People’s Republic, the engineering of contemporary China’s ‘crimson blindfold’ was blinding people to the complex realities both of Communist Party and modern Chinese history. Indeed, purblind historical vision has always been a central feature of the country’s political life.

The following essay offers a short report on the state of that ongoing process from an earlier vantage point.

In my conclusion, I note that:

‘The Maoist or red legacy is no cutesy epiphenomenon worthy simply of a cultural studies’ or po-mo “reading”, but rather it constitutes a body of linguistic and intellectual practices that are profoundly ingrained in institutional behaviour and the bricks and mortar of scholastic and cultural legitimization. It is a living legacy the spectre of which continues to hover over Chinese intellectual life, be it for weal or for bane.’

In the ‘new era’ of Xi Jinping, that spectre — one blithely dismissed as nothing more than ‘mere propaganda that no one really believes’ or overlooked with glib hauteur by bien pensants in the Chinese world, as well as by clutches of academics, politicians, economists and journalists — now undeniably dominates the intellectual, cultural and political life of China. Its looming presence can no longer be denied, and its history, as well as the lacunæ that are integral to that history, demand sustained study.

***

The essay reproduced here was originally presented as a paper at ‘Red Legacies in China’, a conference held at Harvard University. Organised by Jie Li 李潔 and Enhua Zhang 張恩華 and held on 2-3 April 2010, that gathering was jointly sponsored by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation Inter-University Center for Sinology, the Harvard-Yenching Institute and the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

This revised text of that paper formed the final chapter in Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution (Jie Li & Enhua Zhang, eds, Harvard University Asia Center, 2016, pp.355-386). It is reprinted here as a contribution to ‘Over One Hundred Years’, a selection of essays on the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party that features in Spectres & Souls: China Heritage Annual 2021.

As I point out in the notes to this essay, my argument was a continuation of a series of observations that I had made since the early 1990s. Apart from my work on Dai Qing, an ‘investigative historian’ active in the 1980s and New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices (1992), edited with Linda Jaivin, I had also compiled a short survey of the state of official and commercial historical writing titled ‘History for the Masses’ (published as a chapter in Using the Past to Serve the Present, 1993, pp.260-287). In my presentation at Harvard in 2010, however, I drew in particular on the following:

- The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995);

- Shades of Mao: the posthumous career of the Great Leader (1996);

- ‘Time’s Arrows’ (1999);

- In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999);

- ‘The Revolution of Resistance’ (1999, rev. 2004 & 2010);

- ‘I’m so Ronree’ (2006);

- ‘Historical Distortions’ (2006);

- The Forbidden City (2008);

- ‘Beijing, a garden of violence’ (2008);

- ‘China’s Flat Earth’ (2009);

- ‘Beijing reoriented, an Olympic Undertaking’ (2009);

- ‘For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone—was Mao Zedong a New Emperor?’ (2010); and,

- ‘The Children of Yan’an: New Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age 盛世新危言’ (2011).

A continuation of those discussions can be found in my editorial essays and contributions to the first three volumes of The China Story Yearbook series:

- Red Rising, Red Eclipse (2012);

- Civilising China (2013); and,

- Shared Destiny (2014).

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

13 July 2021

***

Homo Xinensis

- The Editor and Lee Yee 李怡, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018

- The Editor and Others, Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part I) — Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, China Heritage, 8 August 2018

- The Editor and Others, The Party Empire — Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part II), China Heritage, 17 August 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis — Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part III), China Heritage, 31 August 2018

- Geremie R. Barmé, A People’s Banana Republic, China Heritage, 5 September 2018, also published as Peak Xi Jinping?, ChinaFile, 4 September 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis Ascendant — Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part IV), China Heritage, 16 September 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis Militant — Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again (Part V), China Heritage, 1 October 2018

***

祭劉曉波謝世四週年

The Thirteenth of July 2021 marks four years since Liu Xiaobo died in custody (see ‘Mourning’).

In the incisive essays that Liu Xiaobo produced until his arrest in late 2008, he repeatedly alerted readers to key aspects of the deep structure of China’s party-state. In particular, he identified in the commingled legacies of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping the autocratic propensities of the People’s Republic. On this sorrowful day, we would encourage readers of China Heritage to re-read some of his work, perhaps starting with:

- Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, ‘Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’, China Heritage, 24 January 2019

As Xi Jinping himself noted in the speech he gave on the podium of Tiananmen on 1 July 2021, only by ‘discerning what appears in the mirror of history is it possible to open up a way to the future’ 以史為鑒,開創未來。

— GRB

***

Red Allure

&

The Crimson Blindfold

Geremie R. Barmé*

This essay was revised as part of ‘The China Story’ project founded in May 2012.[1] In it, I revisit previously published work, some of which has appeared in various scholastic guises as well as in the virtual pages of the e-journal, China Heritage Quarterly (www.chinaheritagequartelry.org).[2]

***

In a number of interconnected spheres a nuanced understanding of what have been called ‘red legacies’ in China as well as more broadly can continue to enliven discussions of contemporary history, thought, culture and politics. In the following I will focus on recent events before offering some observations on history, the Maoist legacy and the knotty issue of academic engagement.

Over the years, I have argued that the aura of High Maoism (1949-78)[3] has continued to suffuse many aspects of thought, expression and behaviour in contemporary China. This is not merely because the party-state of the People’s Republic still formalistically cleaves to the panoply of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought (which has, of course been ‘extended’ by the addition of Deng Xiaoping Theory, Jiang Zemin’s Three Represents and Hu Jintao’s View on Scientific Development). I would argue that, just as High Maoism was very much part of the global revolutionary discourse and thinking in the twentieth century so, in the post-Mao decades, its complex legacies, be they linguistic, intellectual, charismatic or systemic, continue to enjoy a purchase. Furthermore, I support a view that an understanding of Maoism in history and over time, both in terms of empirical reality and in the context of memory, as well as an appreciation of its lingering allure, remain important if we are to gain an appreciation of the ‘real existing socialism’ in the People’s Republic today.

***

***

The Red Patrimony

While some important recent work has noted the ‘long tail’ of Maoist-era institutional practice,[4] I would further affirm earlier scholarship that locates the origins and evolution of what would become High Maoism from the 1950s in cultural and political genealogies of the late-Qing and Republican eras.[5] To this age of revolution we should also be mindful of a longer and overlapping age of reform, one that to all intents and purposes has enjoyed a longue durée: from the externally generated and autocratically imposed reforms, or self-strengthening of the Tongzhi Restoration dating from 1860, through to the Open Door and Reform policies formally initiated by the Chinese Communist Party in late 1978.

When discussing China’s historical legacy we are usually invited by the Chinese party-state to accept a certain narrative arc and its particular official articulation.[6] It is the story not of Chinese greatness as much as the connected tale of the decline in power, economic might and unity of the Chinese world from the eighteenth century, through the century of humiliation (roughly 1840-1949) and the birth of a New China and the two acts of liberation (1949 and 1978). This culminates in the present with the ‘great renaissance of the Chinese nation’ (Zhonghua minzude weida fuxing 中华民族的伟大复兴) formally announced by Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin a decade ago and repeatedly affirmed by General Secretary Hu Jintao on the occasion of the celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the People’s Republic as well as when he marked the centenary of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution on 9 October 2011.[7] It is within this connected narrative that ‘The China Story’ (Zhongguode gushi 中国的故事), itself a relatively recent conceit, has been concocted.[8] It is a story that has been interwoven intimately with the grand romantic narrative of communism. This narrative speaks of the history of the Party in the context of national revolution and independence, it cleaves to Mao Zedong (and a panoply of lesser leaders) as well as many aspects of his career, thought and politics. Although the Communist Party-centric version of that narrative may appear to many to be politically bankrupt in all but name, the appeal of an overarching existential rationale for the power-holders, and indeed for people of various backgrounds who have been immersed in the carefully modulated party-state account of China’s past, remains undiminished.

One of the most abiding legacies of the red era, and one particularly attractive for its advocates regardless of their present political persuasion is the paradigm of the Cold War. In the eternal present of Cold War attitudes and rhetoric, the panoply of devices carefully cultivated during the era of class struggle is easily translated across into the tensions between the People’s Republic of China and its neighbours as well as other developed nations today. The rhetorical landscape over which which the party-state and those in its thrall (from state think-tank apparatchiki and a swarm of left-leaning academics to semi-independent media writers) traverse so comfortably constantly feeds the mimetic grandstanding of the other side in any given stoush.

Since 2009, rhetorical clashes of this kind have revolved around such areas as: climate change, US arms sales to Taiwan, the value of the Renminbi, Internet freedom, territorial issues in the South China Sea, as well as ongoing disturbances in Tibet and Xinjiang.[9] These issues—and here I am concerned with Chinese rhetoric, not the substantive matters involving different national and economic interests—the default position of the Chinese party-state remains that of the early Maoist days when conspiracy theories, class struggle and overblown rhetorical grandstanding formed the backdrop to any official stance.[10] Of course, any discussion of rhetorical opposition cannot detract from real clashes of national interests, worldviews, or political and economic systems.

The Maoist past continues to shape perceptions and discursive practices in the cultural-linguistic realm of China today. Elsewhere, I have noted that the language of ‘totalitarianism’ (that is holistic or totalizing systems in which the party-state—in particular its leaders and theorists—attempts to dominate and determine ideological visions, linguistic practices, as well as social, political and economic policy) as it evolved over many years came to operate according to rules and an internal logic that aid and abet a thought process conducive to its continued sway. In the past this attempt at Gleichschaltung, that is the coordination or ‘intermeshing’ of the inner and outer individual, as well as the various arms and practices of governance, was part of the construction of the socialist enterprise and the ‘new socialist man’. Today, the situation is far more complex as elements of socialism are melded with neo-liberalism and the New China Newspeak of the party-state has been injected with the discursive practices of global managerialism.[11]

In the decades of its ascendancy, as well in the subsequent long years of tenacious reform, the totalitarian in China has exhibited an intriguing versatility, one whereby it has continued to ‘commodify’ or ‘domesticate’ to its particular ends culture, ideas and even oppositionist forces.[12]

We may well ask, however, has revolutionary politics, or even the potency of left-leaning ideas, been entirely evacuated from this story today? Has the neo-liberal turn of Chinese statist politics of recent decades created less a story of revolutionary potential (or even leftist resistance) and more of one that offers an account of self-interest constructed around a concocted ‘Chinese race’, an account the main concern of which is a nationalistic rise on the world stage? Or, do the various red legacies that date from the Republican era (be they communist, socialist or social-democratic) contribute something more than a turn of phrase, a glossy overlay of party culture, and a coherent (and now often glib) account of national decline and revival to China’s political discourse and national mission? If so, then how does the leftist legacy distinguish itself from a failed Maoism? Or is Maoism and its panoply of language and practices the only viable source of resistance besides the discourses of universalism, as well as economic and human rights in China today?

In discussing the past it is of vital importance to appreciate motivating ideas and ideals; in the same token we should be wary of those who would separate for their convenience theory from historical reality (even though the details of that reality themselves may be contested). Some writers on contemporary China and its tangle of traditions find it enticing to engage in what could be called a ‘strategic disaggregation’ of the ideological/ theoretical from the historical/ lived. Without doubt, it is important for thoughtful academics to challenge the crude narratives related to modern Chinese history, be they authored by the Chinese party-state, by the international media, or indeed by a Cold War-inflected academic world. However, in the process equally ham-fisted attempts to ‘recuperate’ elements of Maoism or Chinese-inflected Marxism-Leninism in the context of China’s one-party state can too easily allow people to champion abstract ideas clear of the bloody and tragic realities of the past. Similarly, to privilege Maoism while overlooking the other leftist traditions, the ‘paths not taken’ due to the hegemony of the Chinese Communist Party is to view the past with the same kind of ideological bias of which pro-Maoist writers accuse their liberal and neo-liberal opponents.

Below, in the first instance, I touch briefly on recent events and their background before going on to consider historical narrative, cultural phenomena and intellectual careerism.

***

***

A Red Star Falls Over China

The red patrimony—and indeed it is mostly the construction of male thinkers, activists and power-holders—contains within it a whole range of intellectual artefacts from various points in China’s revolutionary theory and practice. The generation of ‘enemies’ (pace Carl Schmitt and his contemporary acolytes) and the atmospherics of plots and conspiracies are still central to the way that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) channels and responds to the spectres of the past. Although this formerly underground political party has recast itself as a legitimate government with all the paraphernalia of state power, to this day its internal protocols and behaviour recall all too frequently its long history as a covert, highly secretive and faction-ridden organisation. Even under Mao, some commentators called China a ‘mafia-state’. This aspect of the party-state was thrown into sharp relief in February 2012 when the former deputy mayor of Chongqing, Wang Lijun 王立军 a man famed for a time for having attacked that city’s own ‘mafia’, was ordered to undergo an ‘extended period of therapeutic rest’ following his appearance at, and subsequent disappearance from, the US consulate in Chengdu, Sichuan province. The next month, on 15 March, his erstwhile local party leader, Bo Xilai, was dismissed from his various positions and put under investigation.

On 14 March 2012, a day before the sensational news of Bo Xilai’s fall, the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao speaking at what would be his last press conference as the head of China’s government twice referred to the 1981 Communist Party decision on ‘certain historical questions’.[13] That document is one of key importance for an understanding of post-Mao Chinese politics; it also provides the ideological rationale for China’s post-1978 economic reforms. In that carefully worded text the socio-economic policies that had underpinned the Mao era, including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, were formally negated. In March 2012, Wen referred to the 1981 decision in the following way:

‘I want to say a few words at this point, since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, under the leadership of the Party and the government, our country’s modernisation drive has made great achievements. Yet at the same time, we’ve also taken detours and have learnt hard lessons. Since the Third Plenum of the 11th CPC Central Committee [in December 1978], in particular since the central authorities took the decision on the correct handling of relevant historical issues, we have established the line of thinking and that we should free our minds and seek truth from facts and we have formulated the basic guidelines of our Party. In particular, we’ve taken the major decision of conducting reform and opening up in China, a decision that’s crucial for China’s future and destiny.

‘What has happened shows that any practice that we take must be based on the experience and lessons we’ve gained from history and it must serve the people’s interests. The practice that we take must be able to stand the test of history and I believe the people fully recognise this point and I have full confidence in our future.’[14]

Over a year before Bo Xilai was put under investigation for breaching Party discipline, there were overt signs that ideological contestation and a concomitant power struggle were well under way. Since the last major public power struggle within the Chinese Communist Party over two decades ago in 1989, it has become an accepted view of China’s particular brand of one-party consensual authoritarianism that prior to any leadership change jostling for position within the top echelon of the hierarchy takes a number of forms. While it is all but impossible to track effectively the backroom dealings, the power plays and the political feints involved in what is nothing less than a byzantine process, the media still provides some indication of the nature of inner party tussles. Zhongnanhai-ology, however, remains at best an imaginative art. Nonetheless, given the volubility of various critics of the Party since 2009, by early 2011 observers were wondering what had happened to the usually outspoken organs of Party Central.

In late May 2011, the Party did finally make itself heard over the din of fraught contestation. In an opinion piece published by the Central Disciplinary Commission on 25 May, Party members were warned to obey ‘political discipline’ and to cease henceforth from offering unsolicited and wayward views on China’s political future. It declared that a ‘profound political struggle’ presently confronted the Party; it was time to silence idle speculation and furthermore it was necessary to reiterate Party General Secretary Hu Jintao’s ‘Six Absolute Interdictions’ (liuge jue bu yunxu 六个决不允许) for party members—basically, follow the party line and do not engage in public discussions or offer personal opinions; do not fabricate or spread political gossip; and, do not leak state secrets or participate in illegal organisations.[15]

The document noted that there were those who were ‘pursuing their own agendas in regard to party policy and requirements, all the while making a show of being in step with the party; others have been taken in by various stories they pick up, indulge in idle speculation and generate “political rumours”.’ Furthermore, it warned that dissenting party voices were leading to (disruptive) non-party and international speculation about the Communist Party’s leadership and its future. In other words, it could damage the national economy. In 2011-12, the issues of the Maoist legacy were not matters merely of academic interest, they directly impinged on the party-state’s succession plans and more broadly on contending agendas for China’s future direction both at home and internationally. One particular area of contention related to how the Maoist past could, and indeed should, contribute to China’s future.

***

***

Metaphors of History

As rumours circulate—and are energetically denied or dismissed by the authorities—one is reminded of previous episodes in Communist Party history during which rumour-mongering, talk of corruption and the crushing of dissent have been rife. Of course, there is the earliest story related to the writer Wang Shiwei. A critic of Party privilege in the Yan’an period during the early 1940s, he was branded a Trotskyite and traitor. Eventually he was beheaded.

Political rumours (zhengzhi yaoyan 政治谣言) featured during various crucial periods in the People’s Republic as well, in particular during the Maoist years. Given the Party’s control over the media and the secretive nature of its political processes, gossip and rumours have long been the stuff of informal comment on the issues of the day, and the means by which alternative accounts of Party rule circulate. For example, after the founding of the People’s Republic when Mao called on intellectuals and others to help the Party ‘rectify its work style’ in light of criticisms of Party rule in the Eastern Bloc in 1956, many took advantage of the invitation to speak out against the secretive privileges and power of Party cadres. They too were silenced. In 1966, when Red Guard rebels were first allowed to attack the Party they identified privilege, corruption and abuse of power as one of the greatest enemies to the revolution. During this period of Party civil war it was word of mouth and big-character posters that were the common medium employed by individuals and groups to speculate and denounce. Again, around the time of Lin Biao’s fall in 1971, there was a campaign against political hearsay involving Jiang Qing and her famous interviews with Roxanne Witke. Following Deng Xiaoping’s fall in April 1976, the ‘strange talk and odd ideas’ (qitan guailun 奇谈怪论) of July to September 1975 was denounced by the official media. Then, shortly after Mao’s death, when there was a period of relatively free criticism of the purged Party leaders blamed for the mayhem of the Cultural Revolution, privilege and corruption were identified once more as the greatest threat. Another period of political speculation followed shortly thereafter at the time of the Xidan Democracy Wall in 1978-79, and again in 1988-89 leading up to 4 June rumours and speculation were rife. During the 1989 nation-wide protests, some protesters released a detailed account of the connection between Party bureaucrats, their children and the new business ventures that had sprung up during the early stages of reform. (One of the Party leaders named and blamed for the corrupt nexus between Party power, private enterprise and global capital was Zhao Ziyang, later ousted as Party General Secretary.) Even from this cursory sketch we notice that intensified political gossip and official attempts to silence it have been the hallmarks of ruptures in Chinese life for over six decades. Thus, it was no surprise that, shortly following the announcement of disciplinary and legal investigations into Bo Xilai and his wife, Gu Kailai, in April 2012, the authorities announced a new push to quell political rumour mongering. On 16 April, the People’s Daily denied rumours of a coup and that military vehicles had been deployed in the capital;[16] in the days that followed, a series of denials and articles decrying the malign influence of rumour-mongering were published both in the national, as well as the local, media.[17]

The political culture of historical inference, or to use a formulation familiar from the period of High Maoism ‘to use the past to satirize the present’ (jie gu feng jin 借古讽今) or at least to use the past to reflect on the present (yu jin 喻今), is still familiar not only to writers who grew up in the days of Maoism and its official disavowal (1978-1980s), but also for writers today. One could argue that historical metaphors are part of the fabric of Chinese social and cultural life that far predate the Mao era.[18] There is no doubt that finding esoteric meanings, clues to contemporary politics, messages for the masses, and so on in plays, novels and movies, was a central feature of Maoist-era politics and cultural life. During the post-Cultural Revolution disavowal of the politics of the purge and mass campaigns, this use of history and culture was decried as being a ‘historiography by [political] inference’ (yingshe shixue 影射史学).

Despite this, in the penumbra of politics, a popular market for revelations about the inner workings of power continues to this day, something evident most recently in the wave of microblog comments on the Chinese Internet surrounding the fate of former Chongqing Party boss Bo Xilai and his family.

Rumours have a venerable history in modern China. At the end of the Qing dynasty, for example, rumours about court politics abounded. They filled accounts known as ‘wild’ or ‘untamed histories’ yeshi 野史; they provided an alternative to the formal records of the time. While the new Republican government would appoint a bureau to oversee a writing of a formal Qing history (a controversial and flawed enterprise that produced a Draft History of the Qing 清史稿), these unofficial or ‘wild histories’ proliferated. As the historian Harold Kahn has noted of wild histories:

‘Official history adjusted the record to suit the needs of the court; unofficial history embroidered it to meet the tastes of a broader, less discriminating public. And it is this embroidered record which has formed the stable of much of China’s popular historical thought.’[19]

Exactly a century ago, shortly following the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, scabrous revelations about the inner workings of the defunct imperial court, as well as speculation regarding some of the most notorious incidents in the Qing dynasty, became the stuff of popular history writing and literature. There were, for example, stories about the rumoured marriage between the empress dowager Xiaozhuang 孝庄 (d.1688) and her brother-in-law Dorgon 多尔衮; details of the imperial prince Yinzhen’s 胤祯 usurpation of the throne following the death of his father the Kangxi 康熙 emperor; hearsay to do with the Yongzheng 雍正 emperor’s sudden demise; discussions about the questionable relationship between the minister Hešen 和珅 and the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor; details related to the invasion of the Forbidden City during the Jiaqing 嘉庆 reign; lascivious accounts of the addictions (and afflictions) of the youthful Tongzhi 同治 emperor in the 1870s; talk about what went on between the Empress Dowager and the eunuch Li Lianying 李莲英; dark mutterings surrounding the mysterious demise of the Guangxu 光绪 emperor (he predeceased the Empress Dowager by a day); and so on and so forth. What were illicit, unofficial accounts in the past provided fodder for readers who had access to a booming publishing market, and with due consideration of the anti-Qing sentiment of the early Republic were anxious to see fun made of the defunct imperial masters while at the same time as indulging in patriotic entertainment.

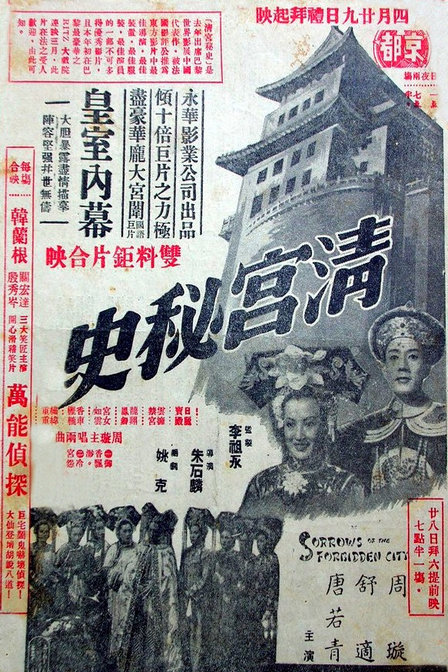

After 1949, the modern tradition of employing fiction or unofficial histories to reveal and speculate on the inner workings of China’s rulers (not only dynastic, but also Republican, and eventually communist) continued to flourish, but in Hong Kong. That is until political change, and a commercial publishing boom, transformed the media landscape in both China and Taiwan from the late 1970s. It is also perhaps hardly a coincidence that the first, albeit unsuccessful, cultural campaign of Maoist China was also one that involved with historical verdicts and revelations of inner-court wrangling. This was the criticism that Mao Zedong launched shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic of the Hong Kong film The Secret History of the Qing Court (Qinggong mishi 清宫秘史, 1948).[20]

The very culture of Emperors, Kings, Ministers and Generals (di wang jiang xiang 帝王将相), as well as that of Talented Scholars and Beauties (caizi jiaren 才子佳人) collectively excoriated in the early years of the People’s Republic and then actively denounced as part of the prelude to the Cultural Revolution era has, since the 1980s, become part of the mainstream once more. The production of Chinese historical costume dramas had previously been the province of TV and film-makers in Hong Kong and Taiwan, but it was in the 1990s, and as a result of voracious TV audiences and a political environment that was more willing to accept the previously excoriated ‘feudal’ past, that numerous interpretations of the imperial era appeared in the form of ‘fanciful accounts’ (xishuo 戏说) of emperors and empresses variously in their youth, at the height of their powers and in their dotage. One of the first of these was the 1991 Taiwan-mainland coproduction A Fanciful Account of Qianlong (Xishuo Qianlong 戏说乾隆), a forty-one-part TV series about the Qianlong emperor’s Tours of the South, based on a fictional account of the ruler’s supposed exploits during three of his provincial progresses.[21] The ‘fanciful account’ genre would eventually become a version of historical narrative characterized by semi- or completely farcical re-countings of historical incidents, figures or even past fictions for the sake of popular entertainment. Films and TV shows in this semi-parodic style would proliferate.

The recapturing of the past through such humorous and often lubricious fictions was liberating, and it has appeared to challenge the historical schema formalized during the early decades of the People’s Republic. However, the actual story may be somewhat more complex. The rehabilitation of traditional history and story telling, in particular in the form of popular history, since the advent of policies to promote ‘spiritual civilisation’ first spoken of in 1979 and then pursued from the mid 1980s, serves well the political status quo. This is because the revival of the past is still, for the most part, expected to conform the contours of national history as delineated in the Maoist-era temporal landscape. This timescape was itself developed over many decades on the basis of debates about Chinese history, periodization, economic development and social change, from the time of the New Culture Movement (roughly 1917-27).[22] Popular accounts of the imperial past aided the Party’s overarching efforts to reintegrate the history of dynastic China, and the country’s greatness, into the modern record and the broad narrative of national revival discussed earlier.

The popular fictionalization of history, however, has hardly been limited to the dynastic past, nor has it simply accorded with official dictates. Film and fiction accounts of both Republican and Communist Party history accord with guidelines set down by the party historians and propagandists. This policing of the past has been particularly prevalent since an incident in 2003 involving the multi-episode TV series, Towards a Republic 走向共和. Produced to mark the 1911 Xinhai Revolution and the founding of the Republic of China the series was, at first glance, a relatively run-of-the-mill costume drama, mixing as it did elements of theatricality with serious history. The writers of Towards a Republic, who included liberal Qing historians, offered a view of the 1911 Revolution that challenged not only the Party’s interpretation of the past but one that was also an indictment of its present autocratic behaviour.

The sixty-part series had a finale in which the father of the nation, Sun Yat-sen, appears to be addressing the viewing audience directly, and it was politically explosive. As he explains the symbolism of what we know as the Mao suit (Zhongshan zhuang or ‘Sun Yet-sen suit’ in Chinese), Sun describes each of the buttons and pockets as representing parts of his political program—economic progress, democratization and the separation of powers. He then addresses the viewer:

‘I have thought long and deep in recent times: how is it that so many feudalistic and autocratic things have appeared time and again in our new Republic? If this is not dealt with, it is inevitable that the autocracy will reign once more; the Republic will forever be but a mirage.

‘The idea of a Republic is based on equality, freedom and the love of humanity. But over the past six years we have been witness to how government bureaucrats at every level have treated the law like dirt; how the people have been enslaved.

‘A Republic [literally, ‘a people’s state’] should be a place of freedom; freedom is the heaven-given right of the people.

‘But over these six years we have witnessed the power-holders enjoying freedom. The more power you have the more freedom you enjoy; the less power you have the more circumscribed your freedom. The people have no power, so they have no freedom…

‘The Republic should be governed by the rule of law, but over the past six years we have seen administrative power used repeatedly to interfere with the operation of the law. If you are not obedient I’ll buy you off; if you fail to comply I will arrest you, or have you killed. Lawmakers have been prostituted by the power-holders who have their way …’[23]

When the series was rebroadcast this material had been removed. As a result of Towards a Republic, in 2004 the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television established a new oversight group that would now police the production and censoring of all materials not only related to the revolution but of history overall.[24] It was this same government group that in early 2011, as rumours and power-play swelled in Beijing and elsewhere, placed a ban on films and TV shows that speculated either about the past or the future. As political speculation unsettled Party equanimity, the possibility that people could contemplate alternative scenarios also seemed unsettling. In particular, shows featuring time travel (known as chuanyue ju 穿越剧) were interdicted as they ‘lack positive thoughts and meaning’[25] and ‘goes against Chinese heritage’.[26]

As issues to do with democracy and authoritarianism are debated more heatedly in China today than they had been for years, we can also detect a nostalgia for a past in which a different kind of future was imagined, as opposed to a present in which the past is constantly being marshalled, trimmed and massaged to legitimate the Party. As film and TV accounts of the past proliferated through the 1990s and into the new millennium, a new category of revived culture appeared, that of the ‘red classic’ (hongse jingdian 红色经典). First promoted as part of the patriotic education campaign instituted following the events of 1989 to teach both students and wider audiences about the history of the revolution and the dangers that had, and that continue, to beset it, ‘red classics’, or old propaganda movies were rebroadcast nationwide. In more recent years as media offerings have proliferated, a new genre of culture has developed under the old rubric of the ‘red classic’. These include not only films and TV shows, but also songs, novels, poems and art works. Collectively they form a narrative of revolution that has been stripped of revolutionary politics but which retains a highly romantic depiction of the past and its achievements in which the glories of the party are intertwined with accounts of heroism, love, sacrifice and noble aspiration.

Until the appearance of the ‘sing red’ campaign championed by the Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai and his supporters in 2009, the ‘red classic’ genre was easily derided as being of marginal interest and importance in understanding contemporary China and its worldview. I would ask rather: is the corpus of ‘red classic’ works merely fodder for the avaricious maw of a media market that must work with the material available, and as such has little greater significance? Or, rather, is it part of the very skein of modern mainland Chinese culture that through repetition and adaptation normalize the historical narrative of the modern party-state? And, if that is case (even partially) does the de-politicized narrative of the revolution not cannily employ petit-bourgeois sentimentality in the place of allowing for, or rather allowing audiences to imagine, significant social change? Or is there some greater more ‘progressive’ potential in the repetition of familiar cultural ‘classics’, so much so that in fact these works re-domesticate the revolution so that concepts of social justice, fairness and freedom that were so important during the long years of struggle before 1949 could be portrayed for an interested contemporary audience? Or should these concerns be swept aside as it is all just commercialized fun and a story about canny media players cynically taking advantage of party-state dictates to promote and produce uncontroversial material? Is it yet another chapter in the degradation of the sublime (chonggao 崇高) that the novelist and former Minister of Culture Wang Meng 王蒙 decried in the 1990s? Or, perhaps, can we detect in the remakings, spoofs and recountings of High Maoist policies, cultural styles and forms ways in which the impotent, powerless and dispossessed can express opposition to the eternalizing presumption of a party-state, one that maintains its dominion over the mainstream historical narrative, national identity and real political power? Is this ‘resistance within’ also not part of the red legacy—the opposition to the party’s theory-led monopoly on discourse, ideas and everyday politics? It is an opposition that took many forms in the Maoist years—be they rightist and leftist—but it was against the monopoly of control, and it is one of the most trenchant dimensions of the legacy that some may merely wish to see in terms of Maoist ideology.[27]

It is in the paradoxical relationship between history and memory that we find compelling evidence of the long shadows of the Maoist legacy. Put crudely, memory consists of those subjective acts or re-callings of events, people and experiences, while history is a more formal way of generating narratives of collective experience. Some schools of historians see historiography as providing a corrective to accidental or purposeful ‘mis-remembering’, that is history making that is aimed at serving particular partisan groups or causes. In the mainstream of China today, historical narratives are underpinned by determined practices of misremembering aimed at presenting a series of overlapping party-state narratives of Chinese history. Repeated, and contending, revisiting and reevaluations of history are not encouraged by the official overculture or its funded institutions. Major historical verdicts are determined (the so-called dinglun 定论) and, by and large, are not up for re-evaluation or further investigation and debate. In this we find the ‘final solution’ of the Maoist approach—cases once decided, or overturned are not to be ‘turned over’ again, or to be put on their sides and considered from new and different angles.

In any discussion of Maoist legacies in modern China it is necessary to remain alert to the numerous lacunæ and distortions in the public historical account that are encouraged and reinforced in the mass media and in the tireless iterations of officialdom. In such accounts those incidents or periods that do not warrant a place by the very nature of their absence find no place in history and fall from memory. Such ‘memory holes’, to use a Soviet-era expression, are not perhaps as actively constructed as during the hey-day of Maoist China, but the practice of historical obliteration remains an important institutional legacy of the past.

***

***

Waving the Red Flag to Oppose the Red Flag

History, distorted accounts of the past and the power of metaphor have all played a role in the unfolding of recent Chinese political dramas, just as they have engaged with the Maoist legacy in complex ways.

In April 1984, a group of students who had graduated from elite Beijing middle schools created an informal association to celebrate their camaraderie and their origins. They called themselves the Fellowship of the Children of New China (Xinhua Ernü Lianyihui 新华儿女联谊会).[28] At the time of the centenary of Mao Zedong’s birth in 1993, the group renamed itself the Beijing Children of Yan’an Classmates Fellowship (Beijing Yan’an Ernü Xiaoyou Lianyihui 北京延安儿女校友联谊会). Its members were the descendants of men and women who had lived and worked in the Yan’an Communist base in Shaanxi province from the 1930s to the 1940s, as well as the progeny of the party who were born and educated in Yan’an. From 1998, the group held annual gatherings to coincide with Spring Festival (Chinese New Year), as well as a range of other events organized around choral and dancing groups, Taijiquan classes, and painting and calligraphy activities. In 2001, they shortened their name to the Beijing Children of Yan’an Fellowship.

From 2002, the Children of Yan’an was led by Hu Muying 胡木英, daughter of Hu Qiaomu 胡乔木, a Party wordsmith par excellence and Mao Zedong’s one-time political secretary. In 2008, the fellowship expanded its membership to include people with no specific link to the old Communist base and its revolutionary éclat. With a core membership of some one hundred people, the Children of Yan’an not only boasted the leadership of Hu Muying, but also the key participation of Li Min 李敏 (Mao Zedong’s older daughter), Zhou Bingde 周秉德 (Zhou Enlai’s niece), Ren Yuanfang 任远芳 (party elder Ren Bishi’s 任弼时 daughter), Lu Jianjian 陆健健 (former party propaganda chief Lu Dingyi’s 陆定一 son) and Chen Haosu 陈昊苏 (son of Chen Yi 陈毅, the pre-Cultural Revolution party-state Mayor of Shanghai and later Minister of Foreign Affairs). On 13 February 2011, the group held their annual Chinese New Year gathering in the auditorium of the 1 August Film Studio, an organization under the direct aegis of the People’s Liberation Army.

On that occasion, apart from the Children of Yan’an, a range of other interested groups, or what were dubbed ‘revolutionary mass organisations’ were also present.[29] During the speech-ifying that day these various attendees were collectively represented by Chen Haosu, himself a former film and TV bureaucrat with a noble party lineage that we have noted above. The Children of Yan’an Fellowship itself was represented by Hu Muying and her deputy, Zhang Ya’nan 张亚南, formerly the Political Commissar of the PLA Logistics Department and previously secretary to Wei Guoqing 韦国清, a Cultural Revolution-era Vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress.

Following a series of platitudinous remarks and a brief recounting of the long years of struggle that their revolutionary forebears had gone through to found New China (an account that, not surprisingly, glossed over the bloody horrors of the first three decades of party rule from 1949 to 1978), Hu Muying said:

‘The new explorations made possible by Reform and the Open Door policies have, over the past three decades, resulted in remarkable economic results. At the same time, ideological confusion has reigned and the country has been awash in intellectual currents that negate Mao Zedong Thought and Socialism. Corruption and the disparity between the wealthy and the poor are of increasingly serious concern; latent social contradictions are becoming more extreme.

‘We are absolutely not ‘Princelings’ (Taizi Dang 太子党), nor are we “Second-generation Bureaucrats” (Guan Erdai 官二代). We are the Red Successors, the Revolutionary Progeny, and as such we cannot but be concerned about the fate of our Party, our Nation and our People. We can no longer ignore the present crisis of the Party.’[30]

Hu went on to say that through the activities of study groups, lecture series and symposia the Children of Yan’an had formulated a document that, following broad-based consultation, would be presented to Party Central. The document was entitled ‘Our Suggestions for the Eighteenth Party Congress’ (Women dui Shiba Dade jianyi 我们对十八大的建议).[31] ‘We cannot’, Hu continued:

‘be satisfied merely with reminiscences nor can we wallow in nostalgia for the glorious sufferings of our parent’s generation. We must carry on in their heroic spirit, contemplate and forge ahead by asking ever-new questions that respond to the new situations with which we are confronted. We must attempt to address these questions and contribute to the healthy growth of our Party and help prevent our People once more from eating the bitterness of the capitalist past.’

For his part, Zhang Ya’nan declared that China’s Communist Party, the Communist cause and Marxism-Leninism itself were being directly challenged and indeed disparaged by the enemies of the revolutionary founding fathers. In particular, he despaired at the de-Maoification that continued to unfold in China. He reminded his audience that ‘Chairman Mao bequeathed us four things: one piece of software and three pieces of hardware. The hardware is the Chinese Communist Party, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Republic of China. The software is Mao Zedong Thought.’ Zhang went on to praise the Red Culture campaign launched by Bo Xilai in Chongqing in 2008, the work of Luo Yuan 罗援 and the writings of Zhang Tieshan 张铁山. He then commended to his audience the document formulated for the Party’s upcoming Eighteenth Congress. He declared that it was a manifesto that gave voice to their wish ‘to love the party, protect the flag and to revitalize the as-yet-unfinished enterprise of the revolutionary fathers’. He also suggested that the Children of Yan’an should invite activists who were involved in the Mao Zedong Banner website 毛泽东旗帜网 and the Workers’ Network 工人网 to their next Spring Festival gathering in January 2012.[32]

The Children of Yan’an site made no mention of the 2012 Spring Festival, which, in the event, was a low-key affair. After all, as we have noted in the above, by then the ‘atmospherics’ of Chinese politics had undergone a dramatic transformation. Wang Lijun had made his dramatic visit to the American Consulate in Chengdu, By mid March, around the time of Bo Xilai’s fall, key leftist or revivalist-Maoist sites such as Utopia, Mao Zedong Banner (Mao Flag) and Red China had been suspended by the authorities; Workers’ Network, however, remained active.[33] One could summarize the views of this informal comradely coalition, one that is based both in China and overseas, in the following terms: China’s party-state system (from the party, army and government bureaucracy, through to the legal system and academic) has for the most part fallen under the control of agents who in the long run are working for foreign interests; the mainstream Chinese elite consists of pro-US spies. In response to the incursions of global capital in China, it is necessary to re-nationalize all assets, abolish private enterprise and the non-state private market, as well as to reinstitute central economic planning. By and large, these groups reaffirm the centrality of class analysis and class struggle as in the nation’s political life, some declare that it is necessary to obliterate ‘bourgeois elements taking the capitalist road’ in all areas of government. Among other things, some have called for a reform of China’s legal could that would introduce a death penalty for ‘traitors’, and they compiled a list of writers, editors and intellectuals who were nominated for elimination.[34]

With their gaze fixed more on the past than the present, the drafters of ‘Our Suggestions for the Eighteenth Party Congress’ reaffirmed the primacy of what is known as the ‘mass line’ (qunzhong luxian 群众路线). First articulated by Mao as early as 1929, the mass line is regarded as being one of the foundations of Mao Zedong Thought. It calls for the party to rely unwaveringly on the masses (a vague and ill-defined group at the best of times), to put faith in them, arouse them, go among them, honestly learn from them and serve them.

The Children of Yan’an declared that their reform proposals were a practical realization of the long-standing principle of the mass line, one that was enshrined in the party’s Constitution and which had in the past ensured the party’s successes. Moreover, they declared that party leaders cannot afford any longer to use social and political stability as an excuse for further delaying substantive reforms to China’s political system. The Children of Yan’an declared that new political talent could be found among the masses, in particular among the enthusiastic party faithful. They claimed, for instance, that the Red Song movement that originated in Chongqing and which later spread nationwide, had seen the appearance of just the kind of enthusiastic younger party stalwarts who would help ensure the continuation of the Communist enterprise long into the future. On the eve of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, Mao Zedong is said to have cautioned that after his demise people would inevitably ‘wave the red flag to oppose the red flag’ (da hongqi fan hongqi 打红旗反红旗).[35] Now it would appear that the Children of Yan’an were using their very own red flag to oppose the red flag of economic reform that, since 1978, had been employed to oppose the red flag of Maoism.

The revival of a patriotic-oriented Maoist ‘Red Culture’ in Chongqing under Bo Xilai would for a time be affirmed (or was it really to be co-opted and marginalized?) by party leaders, in particular by Politburo Standing Committee member and head of the party-state legal establishment Zhou Yongkang 周永康. Around the time that Bo Xilai led a delegation of ‘red songsters’ to Beijing in mid June 2011, Zhou called for the ‘forging of three million idealistic and disciplined souls who are ready to face all dangers with an unwavering faith’. Of importance in the crucible of the engineers of human souls was what would now be called the ‘Five Reds’, that is, ‘Reading red books, studying red history, singing red songs, watching red movies and taking the red path’.[36]

[Note: For an update on how the Children of Yan’an fared during the initial phase of their champion Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption purge, see Barmé, ‘Tyger, Tyger! A Fearful Symmetry’, The China Story, 16 October 2014.]

Not only did the Children of Yan’an formulate a manifesto and agitate for a form of political reform before the looming change of party leadership. It was said that in their pursuit of a new Maoist-style ‘mass line’ they had also tried to engender tentative contacts with grass-roots organizations and petitioner groups in and outside Beijing. For left-leaning figures in contemporary China to engage in such practical, and non-hierarchical, politics was highly significant, especially when considered in contrast to the academic ‘New Left’ (Xin zuopai 新左派) that had arisen in the 1990s and 2000s.

For over a decade the ‘New Left’ intellectuals—a disparate group that, like their rhetorical opponents, the ‘Liberals’, was generally lumped together—had been variously celebrated and derided. In the late 1990s I spoke about the ‘confrontation of caricatures’—that between ‘new left’ and ‘liberal’—that was polarizing the Chinese intellectual world.[37] It is a topic that the intellectual historian Xu Jilin 许纪霖 has frequently addressed since that time. The critics of the New Left claimed that they were primarily ‘on-paper generals’ (zhishang tan bing 纸上谈兵) who could talk up a storm (both in China and at the various international academic fora to which they are frequently invited). They may well profess themselves to being intellectually committed to ‘recuperating’ radical socio-political agendas, critiquing the capitalist turn in China and thinking of how best to utilize the ‘resources’ of Marxism-Maoism in the context of the reform-era. To their critics, members of the New Left rarely seemed to demonstrate any practical desire to deal with the deprived, marginalized, dispossessed or repressed individuals in the society as a whole. Their critics also noted that when issues of free speech or intellectual freedom came up this usually vociferous group were generally silent.[38] While elite members of this leftist claque formed meaty alliances with their global intellectual coevals, on the ground in China protest, resistance and opposition to the oppressive practices of party-capitalism remained the province of lone activists, NGO groups, liberal intellectuals, lawyers and the woefully ‘under-theorised’.

The reticence of members of the New Left is, however, understandable. Apart from the usual intellectual qualms about direct social engagement among those who are more comfortable dealing with academic jousting and refereed publications in prestigious journals, in China principled activism does exact a high price. After all, the engaged intellectual soon confronts a policed authoritarian environment that is infamously punitive. Moreover, the fate of such prominent nay-sayers as Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波 and Ai Weiwei 艾未未 would deter all but the most foolhardy. More disturbing yet is the cruel abuse of numerous (and often nameless) men and women of conscience who have been harried, detained and persecuted by local power-holders and business interests for often the most spurious reasons. One of the issues that this paper returns to in various guises is that, is a pro-Maoist rhetoric the only form of left-leaning critique available to Chinese thinkers and their international supporters? And, if that is the case, are critiques of Mao and his bloody legacy always to be deemed as orientalist, reactionary or pro-neo-liberal?

***

***

Arbitrage

In discussing red legacies it is necessary to be mindful of the long tradition whereby left-leaning causes, and discourse, in China (not to mention elsewhere) have been entwined with a nationalist or patriotic mission related to independence, economic growth and identity politics. In the context of legacy-creation, the Chinese party-state has inherited and invested heavily in the Maoist heritage by transposing social class analysis and the Three-world Theory into the context of contemporary geopolitics. Thus, the People’s Republic, despite its regnant economic strength and international heft, portrays itself as a proletarian-agrarian developing nation that is primarily in solidarity with the dispossessed and under-developed nations against the bourgeois bullies of Euramerica. No matter what elements of truth this self-description may have, as a rhetorical device and canny transmogrification of High Maoist categories, it remains a powerful tool in global power politics, and one area in which the Maoist legacy is particularly vital, and successful.

The trans-valuation of Maoist categories into international relations discourse is only one of the ways in which the heritage persists into the present. Another is the way that rejigged elements of the Maoist canon are employed to bolster careers, to align research projects and to guide personal trajectories. (I would observe that the same holds true even for those who use Maoist-style patriotism to pursue neo-liberal goals, be they academic or mercantile.)

In the late 1990s, a disparate group that I think of as the interrogators of the intelligentsia set themselves apart from the restive throng of their educated fellows to claiming a unique purchase on critical inquiry. In their writings they pursued a project of visualization towards a ‘China imaginary’ that would cast all liberal (and I don’t mean neo-liberal) intellectuals as being of one cloth. As we consider the varied roles of participant‐observers, theorizing non-activists and academic middlemen (among whose number I would, of course, include myself), a term current in the world of international finance suggests itself. It is called ‘arbitrage’, that is ‘the purchase of securities in one market for resale in another.’ As André Aciman comments on the practice in terms of nostalgia and time:

‘As soon as a profit is made, the cycle starts again, with subsequent purchases sometimes paid for with unrealized profit drawn from previous sales. In such transactions, one never really sells a commodity, much less takes delivery of anything. One merely speculates, and seldom does any of it have anything to do with the real world. Arbitrageurs may have seats on not one but two exchanges, the way the very wealthy have homes in not one but two time zones, or exiles two homes in the wrong places. One always longs for the other home, but home, as one learns soon enough, is a place where one imagines or remembers other homes.’[39]

In the context of our own academic pursuits, while one can appreciate divergent agendas for intellectuals who practice their armchair activism in the relatively oblique language of the academy, an accounting for the past requires an approach that is mindful not only of frustrated political agendas and the failure of ideas in practice, but the complex human dimension of ideas in social practice.

In his study and summation of Leszek Kołakowski’s monumental world, Main Currents of Marxism, Tony Judt in particular identifies the abiding attraction of that political philosophy: its ‘blend of Promethean Romantic illusion and uncompromising historical determinism’.[40] Marxism thus, in this account,

‘…offered an explanation of how the world works… . It proposed a way in which the world ought to work… . And it announced incontrovertible grounds for believing that things will work that way in the future, thanks to a set of assertions about historical necessity… . This combination of economic description, moral prescription, and political prediction proved intensely seductive—and serviceable.’[41]

We may well speak of the clever commercialization of China’s red legacy, the canny ways in which elements of the Mao era are insinuated into contemporary political, social and cultural discourse. Some writers and commentators are even still diverted by the tired uses of socialist irony in culture (art, film, essays, blogs, literature and so on). Others may be beguiled by the latest in a long line of attempts to resurrect Marx or indeed Mao himself from ‘distortion’, or the academic subprime market devoted to holistic, globalizing interpretations of the Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin-Mao project. In terms of activism, one legacy of the revolutionary Mao era—that of direct political involvement, organized resistance and struggle, however, seems to be less appealing.[42]

It is here then perhaps that the post-Maoist, Marxist turn in China contributes to our understanding of the categories of the Maoist or red legacy in the new millennium. Needless to say, much can be made of the glib (and cynical) commercialization of red tourism, of the audio-video and digital wallpaper generated in various cultural forms that quote, revive and cannibalize works of high-socialist culture. But has the continuation of one-party rule in China achieved something particular, not merely the party as a particular Chinese phenomenon, and therefore regarded as only being on a national mission of ‘prosperity and strength’, but also something else? I would ask:

- Is the language of the red legacy, its manifestations, merely a sly way of packaging Chinese materialism and worldliness, or is there more at stake and more inherent?

- Are the rabid demands of ‘patriotic-thugs’ (aiguo zei 爱国贼) and official patriots not mirroring the politics of ideological policing and terror that were honed during—or indeed central to—the Maoist era?

- Are the ‘life-sustaining lies’ of the over-culture in the realms of education, media and political discourse part of a longer continuum that enjoy a consanguinity with the Mao era?

While thinkers are at work to salvage Marxism from the egregious failures, and crimes, of Communism (be they of the Soviet or the Maoist variety), an on-the-ground reality in the People’s Republic is that topics couched in Marxist-Maoist terminology remain privileged within Chinese educational institutions, among publishers, think tanks and public as well as funding agencies. The Maoist or red legacy is no cutesy epiphenomenon worthy simply of a cultural studies’ or po-mo ‘reading’, but rather it constitutes a body of linguistic and intellectual practices that are profoundly ingrained in institutional behaviour and the bricks and mortar of scholastic and cultural legitimization. It is a living legacy the spectre of which continues to hover over Chinese intellectual life, be it for weal or for bane. And, as I have pointed out in the above, it is worth asking whether this particular red legacy does in fact leech out the power of other modes of left-leaning critique and thought?

[Note: Readers interested in the attempts by Beijing-Shanghai-Hong Kong-New York-Boston intellectual hucksters and academic shysters to cash in on Bo Xilai’s ‘Chongqing Model’, are encouraged to read ‘The Academics who are Beating a Path to Chongqing’ 奔向重慶的學者們, a no-holds-barred commentary by Rong Jian 榮劍, an independent critic.]

***

***

A Crimson Blindfold

During the ‘history wars’ in Australia that stretched out for a decade from the mid 1990s, historians who brought to light through their research unpalatable truths about the ugly colonisation of the country and the devastation of its indigenous population were condemned by government leaders, right-wing media commentators and others who claimed objectivity. These concerned historians were derided for promoting a ‘black armband’ view of the past. Their historical perspective, one which by its very nature encouraged a heartfelt recognition of a complex history of settlement and a thoughtful reflection on its impact on the present, was seen as being a threat to national cohesion and uplifting narratives of progress and modernity. The power-holders and their media supporters were in turn chided for championing a ‘white blindfold’ view of the national story. In China, the blindfold is of a crimson hue.

Cosy theorizing regarding a supposedly retrievable red legacy had enjoyed a regional boost during the short-lived ‘red renaissance’ championed by the former Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai 薄熙来 and his supporters (political, military and academic) until early 2012. This should not presume, however, that despite the political machinations of Bo and Party leaders, that the red culture of the past is defunct. Some of the key motivating ideas, sentiments and emotions of the Chinese revolution remain part of the fabric of life, and find different levels of articulation and support in the society. To appreciate more cogently the valency of China’s red-suffused heritage, the overlay and interplay of historical tropes, language, practices and evocations is, as I have argued in the above, crucially important for an appreciation of the multifaceted commerce between past and present, traditions real and invented, and the evolution of contemporary ways of being, seeing and speaking in that country today. It is in the realm of the possible that the failures and frustrations of the past also continue to claim a purchase on the future.

Even in power Mao Zedong frequently spoke about the dangers of bourgeois restoration and revisionism. He declared a number of times that he would have to go back into the mountains to lead a guerrilla war against the power-holders, indeed that rebellion was justified. While many discuss the legacy of revolutionary politics in the cloistered security of academic fora, that spirit of rebellion, the active involvement with a politics of agitation, action and danger, is one legacy that seems only safe to contemplate at a distance. Restive farmers and workers in China may cloak themselves in the language of defunct revolution, but evidence suggests that rather than the crude categories of class struggle and revolutionary vanguards, their metaphorical landscape is a complex mixture of traditional cultural tropes and an awareness of modern rights, and ways to stretch social rules.

As we consider the steely determinism of the Marxist lesson, we can detect how that historical determinism and articulations of a Chinese ‘national mission’ dovetail today. The necessity of history remains at the heart of many attempts to find a more capacious meaning within the red legacy. Indeed, as we consider the long tail of Maoism both in, and outside, the People’s Republic of China, we should be alert to the abiding allure, and uses, of the crimson blindfold. After all, it is because of its nature as a belief system—that body of thought, practice, language and cultural heritage that form part of China’s red legacy, a system that has proved serviceable in the past and one that remains seductive today.

***

Notes:

* See Jie Li 李洁 and Enhua Zhang 张恩华, ‘Red Legacies in China — A Conference Report,

Harvard University, 2-3 April 2010′, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 22 (June 2010).

[1] ‘The China Story’ is a web-based initiative of the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) launched in 2012 that includes The China Story website, China Story Yearbook and a China Story archive produced by CIW in collaboration with Danwei Media in Beijing. [Note: Having founded the project in May 2012, my contributions to it came to an end in early 2016.]

[2] For some essays relevant to this topic, see: ‘Time’s Arrows’ (1999); ‘The Revolution of Resistance’ (1999, rev. 2004 & 2010); ‘I’m so Ronree’ (2006); The Forbidden City (2008, 2009, 2012); ‘Beijing, a garden of violence’ (2008); ‘China’s Flat Earth’ (2009); ‘Beijing reoriented, an Olympic Undertaking’ (2010); ‘For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone—was Mao Zedong a New Emperor?’ (2010); and, ‘The Children of Yan’an: New Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age 盛世新危言’ (2011). For an early book devoted in part to these issues, see Shades of Mao: the posthumous career of the Great Leader (1996), and for a work that notes the abiding legacies of the Maoist era during the 1980s and in particular during the Protest Movement of 1989, see the narration of The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995), at www.tsquare.tv, of which I was the principal author.

[3] I would suggest a simple division of Maoism into: a pre-1949 form; that of High State Maoism when the complex body of thinking, policies and personality cult held sway in China from 1949 until the end of 1978 (and the launching of the reform era); the 1978-89 decade of contestation; the 1989-99 decade of recalibration; and the 1999- era in which Maoist and Marxist legacies have found new champions both inside and outside of officialdom. Such a schema is but a crude convenience.

[4] See, for example, Sebastian Heilmann and Elizabeth J. Perry, eds, Mao’s Invisible Hand: The Political Foundations of Adaptive Governance in China, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2011.

[5] Elizabeth Perry’s work on the miners of Anyuan offers a particular account of the domestication of revolution in China. See Elizabeth J. Perry, Anyuan: Mining China’s Revolutionary Tradition, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012.

[6] See William A. Callahan, China: The Pessoptimist Nation, Oxford University Press, 2009.

[7] See, for example, such analyses as: ‘ “Sange daibiao” yu Zhonghua minzu weidade fuxing’, 8 February 2002 at: http://www.bjqx.org.cn/qxweb/n807c5.aspx; and, ‘Zhengque lijie Zhonghua minzude weida fuxing’, 27 January 2007, at: http://www.bjqx.org.cn/qxweb/n7499c5.aspx. Hu Jintao used the expression ‘Chinese national revival’ (Zhonghua minzu fuxing) twenty-three times during his 9 October 2011 Xinhai speech. See ‘Hu Jintao 23 ci ti Zhonghua minzu fuxing, minzu fuxing bixu zhaodao zhengque daolu’, in Nanfang ribao, 10 October 2011, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/15842000.html. For a recent comment on various aspects of this narrative as generated in China and internationally, see William A. Callahan, ‘Sino-speak: Chinese Exceptionalism and the Politics of History’, The Journal of Asian Studies, vol.71, no.1 (February 2012): 1-23.

[8] For more on this, see my analysis of the Opening Ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, ‘China’s Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008’, The China Quarterly, 197 (March 2009): 64-86; and, my ‘Telling Chinese Stories’ presented at The University of Sydney, 1 May 2012.

[9] Although US-based academic audiences will invariably see things through the particular (dare I say ‘distorting’?) prism of US-China-specific relations, for those of us in the Antipodes the various kerfuffles in 2009 involving the Sino-Australian relationship over the aluminum corporation of China Chinalco’s investment plans, Stern Hu’s arrest in Shanghai (and March 2010 trial) and the visit of the Ughyur activist Rebiya Kadeer to Melbourne, are more salient. For more on this, see China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse, ANU, Canberra: Australian Centre on China in the World, 2012.

[10] See, for example, Qiang Zhai, ‘1959: Preventing Peaceful Evolution’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 18 (June 2009), at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=018_1959preventingpeace.inc&issue=018; and, my essay ‘The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 21 (March 2010), at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=021_peacefulevolution.inc&issue=021.

[11] For an extended essay on New China Newspeak, see the entry in the China Heritage Glossary, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 29 (March 2012) and here.

[12] This is the particular focus of my 1999 book In the Red, on contemporary Chinese culture, New York: Columbia University Press.

[13] ‘Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China (Adopted by the Sixth Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on 27 June 1981)’, available online at: http://www.marxists.org/subject/china/documents/cpc/history/01.htm

[14] http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/03/14/china-npc-highlights-idUSL4E8EE11K20120314

[15] See ‘Jianjue weihu dangde zhengzhi jilü’, online at: http://opinion.people.com.cn/GB/14727703.html; and the independent commentary at: http://www.chinese.rfi.fr/中国/20110525-中纪委警告中共党员莫对重大政治问题“说三道四”.

[16] See ‘ “Junche jin Jing” yaoyan jiyi yingxiang wending’, Renmin ribao, 16 April 2012, online at: http://news.cn.yahoo.com/ypen/20120416/989582.html

[17] See, for example, Zhang He, ‘Yao renqing wangluo yaoyande shehui weihai’, Renmin ribao, 16 April 2012, online at: http://news.qq.com/a/20120416/000160.htm, and so on.

[18] This is a point made at length by Paul Cohen in his 2007 book Speaking to History: The Story of King Goujian in Twentieth-Century China, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[19] Harold L. Kahn, Monarchy in the Emperor’s Eyes: Image and Reality in the Ch’ien-lung Reign, Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 1971, p.51.

[20] In December 2007, the film enjoyed a limited re-release as part of a commemoration of the life and career of its female lead, Ruan Lingyu. For more on this, see my The Forbidden City, Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 2008, pp.xxxi & 100; and the online notes at: http://ciw.anu.edu.au/projects/theforbiddencity/notes.php?chapter=chapter5

[21] Qianlong xia Jiangnan 乾隆下江南. The TV series was a co-production of the Beijing Film Studio TV Studio and Feiteng Film Company 北影电视部与飞腾电影公司. See also Zhao Zhizhong, ‘Da Qing wangchao re’, in Fu Bo, ed., Cong Xingjing dao Shengjing—Nu’erhachi jueqi guiji tanyuan(Shenyang: Liaoning minzu chubanshe, 2008), pp.373-82. The ‘Fanciful Account of Qianlong’ was soon followed by A Fanciful Account of the Empress Dowager (Xishuo Cixi 戏说慈禧).

[22] See Q. Edward Wang, Inventing China Through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography, New York: State University of New York, 2001.

[23] For the scene, see: http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMTY3Njk2MDA=.html.

[24] See Matthias Niedenführ, ‘Revising and Televising the Past in East Asia: “History Soaps” in Mainland China’, in Steffi Richter, ed., Contested Views of a Common Past, Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 2008, pp.351-69, at pp.364-65.

[25] See David Barboza, ‘Making TV Safer: Chinese Censors Crack Down on Time Travel’, New York Times, 12 April 2011, online at: http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/12/making-tv-safer-chinese-censors-crack-down-on-time-travel/ ; and, for the Chinese document, see: http://www.sarft.gov.cn/articles/2011/03/31/20110331140820680073.html

[26] See http://business.blogs.cnn.com/2011/04/14/china-bans-time-travel-for-television/

[27] ‘De-politicized politics’ is a term grafted from the work of Wang Hui. See also Yang Jinhong, ‘Man tan “hongse jingdian” gaibian’, at:http://qkzz.net/article/f3ab77d9-5b11-4cfa-9b16-050c70ada9d7.htm.

[28] This overview is based on material available at the Children of Yan’an website. See: http://www.yananernv.cn/geren.html.

[29] These groups included: 新四军研究会、井冈儿女联谊会、十一同学会、红岩儿女联谊会、西花厅联谊会、

北京八路军山东抗日根据地研究会、太岳精神传承会、抗联儿女联谊会、冀中研究会、西路军儿女联谊会筹备组、开国元勋合唱团、北京十一同学会、101中同学会、育才同学会、八一同学会、华北小学同学会、育英学校同学会. All of them boast complex backgrounds, affiliations and party-state-army connections.

[30] For Hu’s speech, see: ‘Hu Muying huizhang 2 yue 13 ri zai Yan’an ernü lianyihui tuanbai dahuishangde zhici’, online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2425.html.

[31] For details, see: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2427.html.

[32] For Zhang Ya’nan’s speech, see ‘Chunjie tuanbaihui zhuchici (zhailu)’, online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2428.html. The ‘de-Maoification’ referred to by Zhang was actually a formal process launched by the Chinese Communist Party in the late 1970s. In recent years, however, more detailed critiques of Mao and his period of rule have been published by those with less sympathy for the Communist cause. One of the most recent of these appeared in April 2011, some two months after Zhang Ya’nan’s handwringing. It was by the academic Mao Yushi 茅于轼: ‘Return Mao Zedong to Humanity—on reading The Sun Also Falls’ (Ba Mao Zedong huanyuan cheng ren—du Hongtaiyangde yunluo), online at: http://china.dwnews.com/news/2011-04-26/57658778.html.

[33] See See Robert Foyle Hunwick, ‘Utopia website shutdown: interview with Fan Jinggang’, 14 April 2012 on Danwei, online at: http://www.danwei.com/interview-before-a-gagging-order-fan-jinggang-of-utopia/. See also: http://maopai.net/

[34] On 28 December 2011, the Maoist revanchist site Utopia published the results of a year-end poll on China’s top traitors (乌有之乡: 评选’十大文化汉奸’). The CIW-Danwei Online Archive project provided this news and the decoded list originally published as http://www.wyzxsx.com/Article/Class22/201112/284230.html, now no longer available. The nominees in infamy were: 1. Economist Mao Yushi 茅于轼; 2. History teacher Yuan Tengfei 袁腾飞; 3. Science cop (anti Chinese medicine, etc) Fang Zhouzi 方舟子; 4. Economist Wu Jinglian 吴敬琏; 5. Diplomat Wu Jianmin 吴建民; 6. CCTV host Bai Yansong 白岩松; 7. Military scholar, Mao Zedong and Lin Biao biographer Xin Ziling 辛子陵; 8. Retired government official/ reformer Li Rui 李锐; 9. Legal scholar/ law professor He Weifang 贺卫方; 10. Economist Stephen N.S. Cheung 张五常; 11. Economist Zhang Weiying 张维迎; 12. Economist Li Yining 厉以宁; 13. Southern Weekly deputy general editor Xiang Xi 向熹; 14. Former People’s Daily deputy editor-in-chief Huang Fuping 皇甫平; 15. Writer, Nobel Prize-winning dissident Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波; 16. Former Mao doctor, Mao biographer Li Zhisui 李志绥 (deceased); 17. Peking University journalism professor Jiao Guobiao 焦国标; and, 18. Former People’s Daily editor-in-chief/publisher Hu Jiwei 胡绩伟.

[35] A line from Mao’s famous 1966 ‘Letter to Jiang Qing’ (Mao Zedong zhi Jiang Qingde yifeng xin), officially dated 8 July, although it is highly doubtful that the letter that was released following Lin Biao’s demise in September 1971 was actually composed in 1966.