Wairarapa Readings

Wairarapa Readings 白水札記 celebrate the variety and vibrancy of China’s literary heritage. They introduce literary texts and translations aimed at students of traditional Chinese letters who are interested in the world that lies beyond the narrow confines and demands of contemporary institutional pedagogy. They also reflect the long-term interest of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology in ‘cultivation’ 修養. Henceforth, Wairarapa Readings will be included in ‘Nouvelle Chinoiserie’ under Projects on the China Heritage site.

***

In 1983, John Minford invited me to contribute to a special issue of Renditions 譯叢, the Chinese-English translation journal that he edited at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Titled ‘Chinese Literature Today’ (Renditions, Spring & Autumn 1983) that volume was, in part, inspired by Hexagram LIII Jian 漸 of the I Ching, which reads (in the Wilhelm/Baynes translation):

A tree on the mountain develops slowly according to the law of its being and consequently stands firmly rooted… . Within is tranquility, which guards against precipitate actions, and without is penetration, which makes development and progress possible.

The ‘Trees on the Mountain’ edition of Renditions introduced contemporary Chinese writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and the People’s Republic, as well as their critics. It was generally well received, although one stodgy academic reviewer of our mutual acquaintance felt that the editorial tenor of the work lurched questionably in the direction of ‘Chinoiserie’. John’s response: ‘So it is, so be it.’

Whimsy, delight in literature, playfulness, as well as being able to find a rueful pleasure in the complex traditions of Chinese letters were supposedly out of sync with the requirements of what the academician called ‘The Trade’, that is, contemporary institutionalised scholarship. Thirty-five years later, the animating spirit of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology shares little in common with the near-universal drudgery of academia today: its metrology and methodologies; its theoretical gesturing; its vacuous self-regard.

***

Below John Minford offers readers of China Heritage two stories from Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio about obsession, along with his timely ruminations on ‘Nouvelle Chinoiserie’. Years ago, I described my own approach to the study of ‘things Chinese’ as New Sinology, or Hòu hànxúe 後漢學 in Chinese. It is a term that straddles the vast cultural and intellectual territory between the tradition of Han Studies 漢學 (classical studies evolved from the Han dynasty some two millennia ago) that formed the basis of early Western Sinology in the late-Ming era, and the Chinese academic obsession with modish approaches to knowledge that were lumped together as Hòuxúe 後學, ‘Post Studies’.

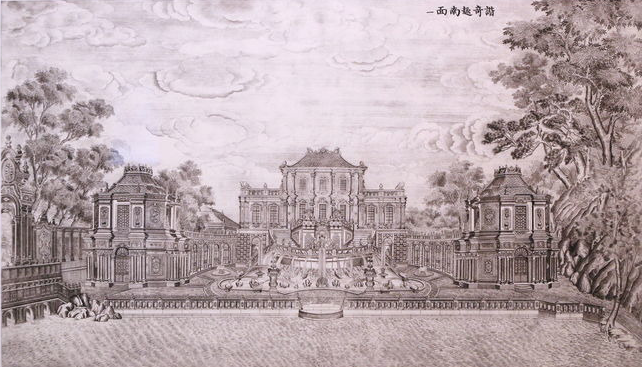

To translate ‘Nouvelle Chinoiserie’ we suggest the term 奇趣漢學 Qíqù hànxúe. In so doing we draw inspiration from the name of a ruined pavilion at the Qing-dynasty Garden of Perfect Brightness — Yuanming Yuan 圓明園 — to the northwest of Beijing. The Western Palaces 西洋樓, or follies, were designed for the Garden by Jesuit court missionaries during the eighteenth-century Qianlong reign. They combined the Rococo of Europe with Manchu-Chinese architectural elements (and imagination). One of the main palaces created by the Jesuits was called ‘The Strange in Harmony with the Delightful’ 諧奇趣. Qíqù 奇趣 — the strange married to the delightful — seems to convey best the essence of ‘Nouvelle Chinoiserie’ as conceived by John Minford.

If a cadre in the ever-swelling ranks of sanctimonious academics and intellectual tradespeople chances upon these remarks, one expects (and hopes) that they will be both irritated and properly dismissive.

***

The two stories that follow — ‘The Go Fiend’ 棋鬼 and ‘Bibliomania’ 書癡 — translated by John Minford, are the latest contribution to a new series from Pu Songling’s (蒲松齡, 1640-1715) Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異. The first in the series, The Midget Hound 小獵犬, appeared in these virtual pages on 11 May 2018. For the convenience both of the general reader, and of the interested student, the stories are presented first in English translation and then in the form of an English-Chinese parallel text.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 June 2018

Further Reading:

- New Sinology 後漢學

- On Heritage 遺

- An Educated Man is Not a Pot 君子不器 — On the University

- The I Ching for Beginners

- The Garden of Perfect Brightness 圓明園

Nouvelle Chinoiserie

奇趣漢學

John Minford

This is a term I enjoy using to describe my own slightly heretical take on the New Sinology. The two differ in significant ways: the one seeming to be more political and engaged with contemporary reality, the other more frivolous and concerned with the delights of the past. But they have much in common. They interact. Sometimes the absurd antics of today’s Central Committee read like extracts from the fifth-century New Tales of the World 世說新語; while some of Pu Songling’s merciless eighteenth-century Strange Tales 聊齋志異 read like Lee Yee’s 李怡 biting articles in Apple Daily 蘋果日報.

Our Wairarapa Academy’s recent Longwood Symposium, Dreaming of the Manchus 八旗夢影 (February 2018), took its inspiration from the idealism and aestheticism of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢 and the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion 蘭亭集. But the dark shadows of political repression, past and present, were never far away (the persecution by the Yongzheng Emperor of the family of Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹, the Sima Clan’s destruction of the great Taoist blacksmith-musician Xi Kang 嵇康). The most accomplished poet of the Seven Sages coterie, Ruan Ji 阮籍, with his famous cycle, ‘Songs of my Heart’ 詠懷詩, was a famous instance of the intricate and ambiguous relationship between lyricism and politics. It was no accident that Cao Xueqin took as one of his literary names ‘Dreaming of Ruan’ 夢阮.

Our Symposium discussions of Bannerman Culture were part literary musing, part an obstinate insistence to continue such musings in the face of the current inquisition. They were in fact a revival of the great Chinese tradition of Pure Talk 清談, with all of its attendant pleasures. While celebrating the example of Xi Kang and his high-minded Taoist rejection of public life, we could never forget the tragic circumstances of his death (that he played music on the way to his execution), or that one of his greatest twentieth-century admirers was Lu Xun.

***

Those English noblemen of the eighteenth century, the select members of the Society of Dilettanti, were proudly engaged in ‘making fun of serious things’ (seria ludens). Their goal was to delight (dilettare) in the antiquities of Greece and Rome, to share some of the beautiful things they had seen first-hand on the Grand Tour, to bring archaeology alive. Many of them also adorned their parks and salons with Chinese motifs, and read for pleasure early translations from the Chinese such as The Pleasing History (from the 才子佳人novel 好逑傳, much admired by Goethe) and the huge encyclopedic compendium about China translated from the French of the Jesuit Du Halde. In much the same spirit, I will from time to time present one or two old Chinese gems for the shared delectation of fellow amateurs of our Academy’s website, alongside the more serious contributions of my fellow trustee. And yet, these two latest offerings, from Pu Songling’s Strange Tales, seem to me not to be devoid of contemporary relevance, in an age of multiple obsessions. This I leave the reader to judge.

Amusingly, this very aspiration of mine exposed me a couple of years ago to a most virulent public attack (published online) from an academic teaching in the very nation whose cultural delights I have always wished to share. A learned professor from the National Petroleum University accused me at great length of pandering, in my translations from Pu Songling, to the West’s decadent consumerist tastes (see 任增強, 西方消費文化語境中閔福德聊齋英譯本的四個面向, 《華文文學》, 2016:4). All I can do is plead that the pleasure I was sharing was not my own so much as Pu Songling’s, that notorious lover and chronicler of the strange in its many varied guises. Cao Xueqin, who lived only a few years later than Pu Songling, announces in his brief Apologia that he has written his wonderful novel The Story of the Stone both as ‘a source of harmless entertainment and as a warning to those still in need of awakening’ 可破一時之悶,醒同人之目. The two are not incompatible. The great translator David Hawkes concluded his Introduction to the first volume with the much-quoted words:

‘If I can convey to my reader even a fraction of the pleasure the Chinese novel has given me, I shall not have lived in vain.’

— Featherston

The Wairarapa

31 May 2018

***

Reading Strange Tales:

- John Minford and Tong Man 唐文, ‘Whose Strange Tales?’, East Asian History, Nos.17/18 (June/December 1999): 1-48

- Pu Songling, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異, translated and edited by John Minford, Penguin Classics, 2006

- The Tiny Bird-Track, in The Year of the Rooster, On Reading, China Heritage, 15 January 2017

- John Minford, Herbert Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, a lecture in the series ‘A Lineage of Light’, China Heritage, 25 May 2017

- Weird Accounts 志怪, in Spectres in the Seventh Month, China Heritage, 4 September 2017

- P.K.’s Strange Tales 也斯聊齋, China Heritage, 6 September 2017

- Pu Songling, The Dog Lover (Dog Days II), trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 24 February 2018

- Pu Songling, The Midget Hound 小獵犬 (Dog Days VI), trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 11 May 2018

The Go Fiend 棋鬼

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

A certain Military Commissioner by the name of Liang, stationed in the city of Yangzhou, had recently resigned his command and retired to his home in the country. He enjoyed himself daily roaming through grove and dale, taking with him a supply of wine and a Go set.

One day — it was the ninth day of the ninth lunar month — he had climbed up to a high place, as was the custom at this autumnal festival, and was playing a game of Go with some friends, when a stranger suddenly walked up and stood there silently hovering around them watching the progress of their game with an intent fascination. He showed no signs of wanting to leave. He had a haggard, destitute look about him, and was dressed in rags and tatters, but somehow nonetheless possessed a certain refined and well-bred air. Liang politely invited him to be seated, an offer which he finally accepted, after several expressions of reluctance.

‘I suppose you must be a skilful player of this game,’ said the Governor, pointing to the board. ‘Why not try a round with one of my friends here?’

The stranger at first declined, but finally played a game in which he came off the loser. He seemed greatly distressed by his loss, but was all the more determined to play another round — with the same result, and even greater distress. The others plied him with wine, but he refused to drink a drop and seemed obsessed with challenging his next Go opponent. This went on from morning until well into the afternoon, during which time he never once moved from the board, not even to relieve his bladder.

And then, in the middle of one game, at a crucial moment in the contest, when everything hung on a single move and he and his opponent were beginning to grow excited and exchange heated remarks, he suddenly rose from his seat and stood there with an expression of the utmost terror on his face. He rushed towards the Commissioner, and knelt before him, desperately begging for his protection, kowtowing till his forehead bled. In some perplexity Liang raised him up.

‘Come, it’s only a game!’ he said. ‘Why are you in such a dreadful state?’

‘I beseech you, sir, don’t let your stable-boy bind me by the neck!’ cried the man.

Liang found this request most strange. He asked who this stable-boy was, and the man replied that his name was Ma Cheng. This was indeed one of Liang’s servants, and he sent off to enquire about his whereabouts, only to be informed that he had been in a trance for two days. Now, when the need arose, this Ma Cheng was employed on errands for the Nether World, at the bidding of King Yama, Lord Mutability, the Ruler of Purgatory. He was sometimes obliged to go away on Purgatory business for as long as ten days at a time, serving warrants of arrest on the living. Liang sent instructions for the stable-boy not to be too harsh with his guest. But by now the stranger had already fallen insensible to the ground, and in a matter of seconds had entirely vanished into thin air. Liang sighed in utter amazement. He now understood that the man was a Hungry Ghost,* one of those wretched creatures condemned to wander the earth in expiation of some terrible misdeed. [* Hungry Ghost or 餓鬼 is a translation of the Sanskrit preta. These spirits descend to an unpleasant realm of existence, as retribution for a life of unchecked desire, wherein they suffer continuously from hunger. Some Hungry Ghosts are jailers and executioners working for Yama in the hells, others wander to and fro amongst men, especially at night. — trans.]

The next day, Ma Cheng recovered from his trance and reported for stable duties. Liang summoned him and questioned him.

‘That gentleman,’ replied Ma, ‘hailed from the district between the Yangtze River and the Dongting Lake. He was a confirmed Go addict, and in his lifetime he ruined himself playing the game. His father was greatly distressed by this, and tried confining him in the seclusion of his study. But somehow the son always managed to escape and went off in search of other Go-lovers willing to indulge his fatal addiction in secret. His father repeatedly lectured him on his behaviour, but to no avail. He was quite unable to discipline his son and in the end himself died prematurely, a broken man. In consequence of all these misdeeds, King Yama ordered that the man’s life-span be cut short, and condemned him to join the ranks of the Hungry Ghosts in Purgatory, and wander the earth, in which condition he had already spent seven years.

‘Recently, when the Phoenix Tower on the Eastern Sacred Mount was completed,’ continued the stable-boy, ‘an edict was issued calling for scholars from various districts of the earthly realm to compose inscriptions for it. King Yama released your gentleman temporarily from his sentence, in order that he might be able to respond to this call and thereby earn some more permanent dispensation. But the man, led astray by his addiction, dawdled on the way, and has by now long exceeded the time-limit. The Lord of the Sacred Mount sent me to report to King Yama the new crime of which the man was now guilty. King Yama was greatly angered and ordered me to search for him everywhere and apprehend him. A day or two ago you sent me instructions to treat him kindly, so I refrained from binding him straightaway by the neck.’

Commissioner Liang enquired what had now become of the unfortunate man.

‘He is permanently employed in Purgatory,’ replied Ma, ‘and can never be born again in this world.’

The Governor sighed.

‘Such are the terrible consequences of addiction!’

Parallel Text

The Go Fiend 棋鬼

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

A certain Military Commissioner by the name of Liang, stationed in the city of Yangzhou, had recently resigned his command and retired to his home in the country. He enjoyed himself daily roaming through grove and dale, taking with him a supply of wine and a Go set. 揚州督同將軍梁公,解組鄉居,日攜棋酒,游翔林丘間。

One day — it was the ninth day of the ninth lunar month — he had climbed up to a high place, as was the custom at this autumnal festival, and was playing a game of Go with some friends, when a stranger suddenly walked up and stood there silently hovering around them watching the progress of their game with an intent fascination. He showed no signs of wanting to leave. He had a haggard, destitute look about him, and was dressed in rags and tatters, but somehow nonetheless possessed a certain refined and well-bred air. Liang politely invited him to be seated, an offer which he finally accepted, after several expressions of reluctance. 會九日 登高,與客弈。忽有一人來,逡巡局側,耽玩不去。視之,面目寒儉,懸鶉結焉。然而意態溫雅,有文士風。公禮之,乃坐。亦殊撝謙。

‘I suppose you must be a skilful player of this game,’ said the Governor, pointing to the board. ‘Why not try a round with one of my friends here?’ 公指棋謂 曰: 先生當必善此,何勿與客對壘。

The stranger at first declined, but finally played a game in which he came off the loser. He seemed greatly distressed by his loss, but was all the more determined to play another round – with the same result, and even greater distress. The others plied him with wine, but he refused to drink a drop and seemed obsessed with challenging his next Go opponent. This went on from morning until well into the afternoon, during which time he never once moved from the board, not even to relieve his bladder. 其人遜謝移時,始即局。局終而 負,神情懊熱,若不自已。又著又負,益慚憤。酌之以酒,亦不飲, 惟曳客弈。自晨至於日昃,不遑溲溺。

And then, in the middle of one game, at a crucial moment in the contest, when everything hung on a single move and he and his opponent were beginning to grow excited and exchange heated remarks, he suddenly rose from his seat and stood there with an expression of the utmost terror on his face. He rushed towards the Commissioner, and knelt before him, desperately begging for his protection, kowtowing till his forehead bled. In some perplexity Liang raised him up. 方以一子爭路,兩互喋聒,忽書生離席悚立,神色慘 沮。少間,屈公座,敗顙乞救。公駭疑,起扶之曰:

‘Come, it’s only a game!’ he said. ‘Why are you in such a dreadful state?’ 戲耳,何至是。

‘I beseech you, sir, don’t let your stable-boy bind me by the neck!’ cried the man. 書生曰: 乞付囑圉人,勿縛小生頸。

Liang found this request most strange. He asked who this stable-boy was, and the man replied that his name was Ma Cheng. This was indeed one of Liang’s servants, and he sent off to enquire about his whereabouts, only to be informed that he had been in a trance for two days. Now, when the need arose, this Ma Cheng was employed on errands for the Nether World, at the bidding of King Yama, Lord Mutability, the Ruler of Purgatory. He was sometimes obliged to go away on Purgatory business for as long as ten days at a time, serving warrants of arrest on the living. Liang sent instructions for the stable-boy not to be too harsh with his guest. But by now the stranger had already fallen insensible to the ground, and in a matter of seconds had entirely vanished into thin air. Liang sighed in utter amazement. He now understood that the man was a Hungry Ghost, one of those wretched creatures condemned to wander the earth in expiation of some terrible misdeed. 公又異之,問: 圉人誰。曰: 馬成。先是,公圉役馬成者,走無常,常十數日一入 幽冥,攝牒作勾役。公以書生言異,遂使人往視成,則僵臥已二日矣。 公乃叱成不得無禮。瞥然間,書生即地而滅。公嘆咤良久,乃悟其鬼。

The next day, Ma Cheng recovered from his trance and reported for stable duties. Liang summoned him and questioned him. 越日,馬成寤,公召詰之。

‘That gentleman,’ replied Ma, ‘hailed from the district between the Yangtze River and the Dongting Lake. He was a confirmed Go addict, and in his lifetime he ruined himself playing the game. His father was greatly distressed by this, and tried confining him in the seclusion of his study. But somehow the son always managed to escape and went off in search of other Go-lovers willing to indulge his fatal addiction in secret. His father repeatedly lectured him on his behaviour, but to no avail. He was quite unable to discipline his son and in the end himself died prematurely, a broken man. In consequence of all these misdeeds, King Yama ordered that the man’s life-span be cut short, and condemned him to join the ranks of the Hungry Ghosts in Purgatory, and wander the earth, in which condition he had already spent seven years. 成曰: 書生湖襄人,癖嗜弈,產盪盡。 父憂之,閉置齋中。輒逾垣出,竊引空處,與弈者狎。父聞詬詈,終不可制 止。父憤恨齎恨而死。閻摩王以書生不德,促其年壽,罰入餓鬼獄, 於今七年矣。

‘Recently, when the Phoenix Tower on the Eastern Sacred Mount was completed,’ continued the stable-boy, ‘an edict was issued calling for scholars from various districts of the earthly realm to compose inscriptions for it. King Yama released your gentleman temporarily from his sentence, in order that he might be able to respond to this call and thereby earn some more permanent dispensation. But the man, led astray by his addiction, dawdled on the way, and has by now long exceeded the time-limit. The Lord of the Sacred Mount sent me to report to King Yama the new crime of which the man was now guilty. King Yama was greatly angered and ordered me to search for him everywhere and apprehend him. A day or two ago you sent me instructions to treat him kindly, so I refrained from binding him straightaway by the neck.’ 會東嶽鳳樓成,下牒諸府,徵文人作碑記。王出之獄中, 使應召自贖。不意中道遷延,大愆限期。岳帝使直曹問罪於王。 王怒,使小人輩羅搜之。前承主人命,故未敢以縲紲系之。

Commissioner Liang enquired what had now become of the unfortunate man. 公問: 今日作何狀。

‘He is permanently employed in Purgatory,’ replied Ma, ‘and can never be born again in this world.’ 曰: 仍付獄吏,永無生期矣。

The Governor sighed. 公嘆曰:

‘Such are the terrible consequences of addiction!’ 癖之誤 人也,如是夫。

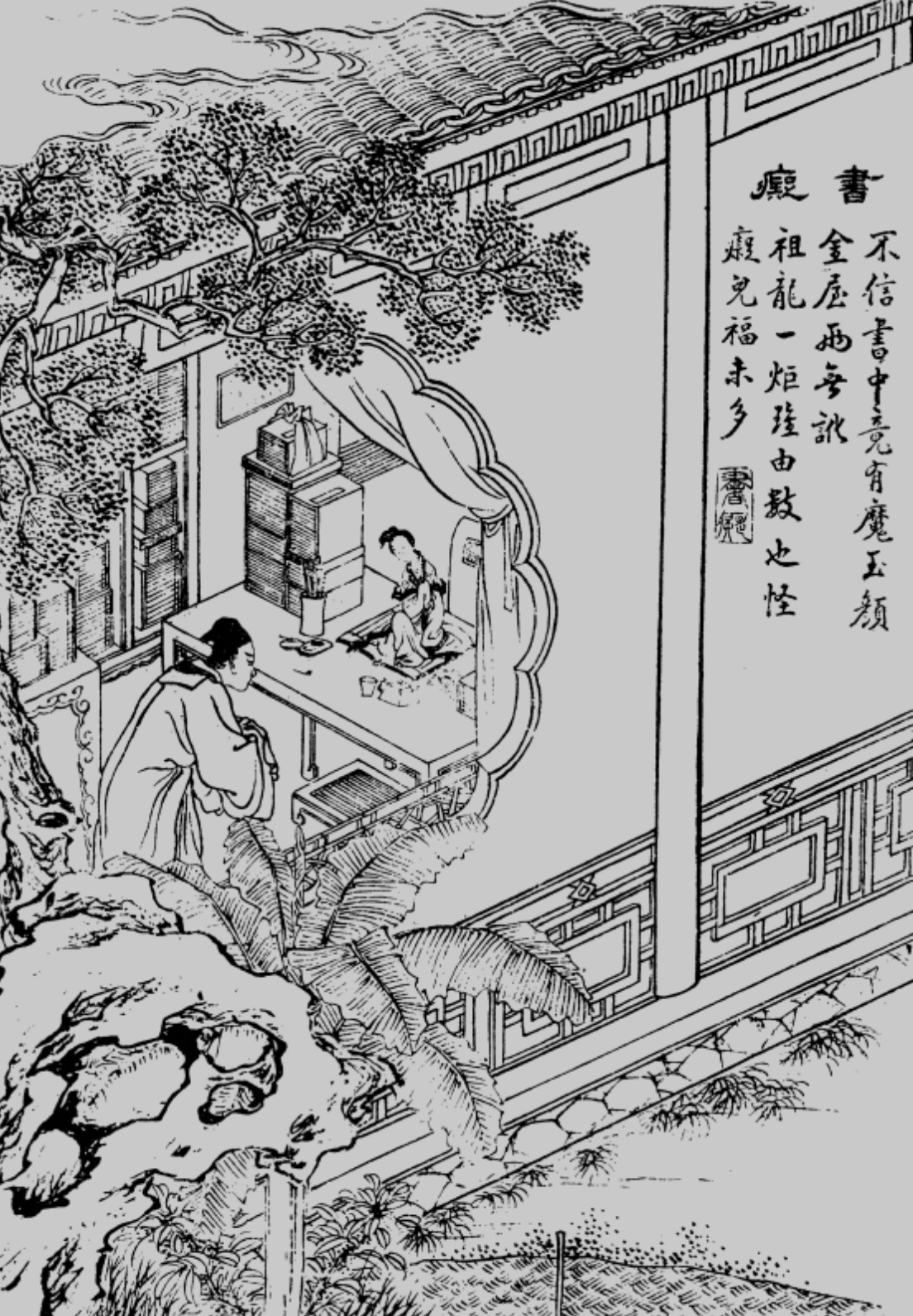

Bibliomania 書痴

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

Lang Yuzhu of Pengcheng City in the province of Jiangsu was the son of a former Prefect, a scrupulous official who had used his salary not to amass personal wealth, but to build up a large private collection of books. His son was even more addicted to books than his father. The family lived in abject poverty, and were obliged to sell everything they possessed merely to survive. And yet, despite this, Lang refused to part with a single one of the books from his father’s collection.

The father had copied out in his own hand for his son’s edification, on a scroll to be hung by his desk, the words of the Song-dynasty Emperor Zhenzong’s ‘Exhortation to Learning’. Lang had the scroll covered with a protective length of white gauze, to save it from fading and from any other sort of damage. The words of the text were as follows:

A wealthy family has no need to buy rich lands,

Abundant grain is to be found in books;

No need of lofty halls,

Chambers of gold are to be found in books;

No need of household servants,

Carriage and horses throng the pages of books;

No need of a go-between,

In books are to be found beauties fine as jade.

Life’s goals can all be reached

Through diligent reading of the Six Classics.*

[*The words of the famous Exhortation are provided not by Pu Songling himself, but by one of the helpful early commentators, Lü Zhan’en (1825), in an interlinear note. — trans.]

Lang did not strive to attain high office or to amass wealth. He genuinely believed that gold and an abundance of grain were to be found in books. To this end he studied earnestly night and day, enduring winter cold and summer heat. He reached the age of twenty without ever seeking a bride, in the sure belief that a beautiful woman would one day come to him of her own accord from within the pages of a book. When friends or relatives called, he was quite incapable of making ordinary conversation. After a couple of perfunctory remarks, he would start mumbling one of his set texts and his guests would sidle awkwardly out of the room. Whenever the Education Commissioner of the Province came on a tour of inspection, Lang always received the highest commendation. And yet, with all this bookish learning, he never once succeeded in passing either of his higher examinations, despite repeated attempts.

One day as he was deeply absorbed in his studies, a gust of wind blew the book from his hand. He hurried after it, and as he did so, the floor suddenly opened up before him. Upon investigation, he found that the cavity beneath the floor contained a mass of rotten grass. Digging it out, he could see that this had once served as a cellar for fodder, which had by now decomposed to form a sort of compost. It was no longer edible, but nonetheless he interpreted its very existence as corroboration of the words of the Exhortation: ‘Abundant grain is to be found in books’. As a consequence he applied himself still more diligently to his books.

On another day, he mounted a ladder to reach a high shelf and there, among a jumble of books, he came across a little golden carriage one foot long. In his joy, he took this too as proof of the words of the Exhortation: that ‘golden chambers, carriages and horses’ would ‘throng the pages of books’. When he showed it to a friend, however, the carriage turned out not to be made of solid gold, but merely gold-plated. He grumbled to himself that perhaps the Ancients had been trying to fool him.

A little while later, a fellow Bachelor-graduate and friend of his father’s, came on a tour as Circuit Intendant. This man was a devout Buddhist. It was suggested to Lang that he should present the gilded carriage to his friend as an ornament for his private shrine. The Intendant was greatly pleased, and gave Lang three hundred taels of gold and two horses in return. Lang was overjoyed, seeing in this indisputable confirmation of the Exhortation’s promise, not only of gold, but of a carriage and horses too. He resolved to be more bookish than ever.

He was now thirty years of age. His acquaintances kept urging him to take a wife, to which his reply was always:

‘The Exhortation says that “beauties fine as jade” are to be found in books. Why therefore should I lament the lack of a beautiful wife?’

And so he buried himself in his books for another two or three years, still with no success in his examinations. People began to mock him. At this time there was a popular saying going around, that the fairy-tale celestial lover, the Weaving Girl, had absconded from her starry home. His friends made fun of Lang, saying:

‘Perhaps it’s you the Heavenly Princess is coming to find!’

Lang paid no heed to their taunts.

One evening, he was absorbed in reading the History of the Han Dynasty and had reached the eighth volume, when, to his utter amazement, half way through the volume, inserted between two pages, he came across a silhouette of a beautiful lady, cut out of silk gauze.

‘Can this really be the “beauty fine as jade” promised in the Exhortation,’ he mused to himself in great disappointment. But when he looked more closely, it was as if he could see her eyes and eyebrows tremble into life. On the reverse side of the gauze were inscribed two tiny and barely legible characters: ‘Weaving Girl’. He marvelled greatly at this. Every day he placed the silk figurine on the cover of his book, and turned her over and over in his hand, deriving the greatest pleasure from simply gazing at her, so much so that he forgot to eat and was quite unable to sleep. One day, as he was thus occupied in his rapt gazing, the lady suddenly bent at the waist and rose. She seated herself on the edge of the book cover, and smiled at him. Lang started at the sight and fell to his knees before his desk. When he stood up, he saw that the lady had already grown to more than a foot in height. He was more astonished than ever, and fell at once to the ground again, knocking his head repeatedly on the floor. Gently she glided down from the desk and stood before him with an air of incomparable beauty and grace.

‘Pray Madam Fairy,’ asked Lang, with a respectful bow, ‘will you tell me who you are?’

She smiled again.

‘My name,’ she replied, ‘is Yan Ruyu, which means Beauty Fine-as-Jade. You have known me now for some while. Day after day you have been gazing at me in rapture, and I had not come to you, there might never be another you in a thousand years, a man willing like you to have such unquestioning trust in the words of the Ancients.’**

[** The surname Yan also means Beautiful. Yan Ruyu sounds like a proper name, while also ‘meaning’ Beauty Fine-as-Jade. — trans.]

Lang was overjoyed, and took her with him to bed. But although he embraced her warmly and affectionately, he had no knowledge of how to engage in what was expected of a man.

From then on, whenever he was at his books, he asked her to sit by his side. She kept urging him not to study so hard, but he paid her no heed.

‘It is because you study so hard that you always fail to pass the examinations,’ she insisted. ‘Just look at the roll of successful candidates at the spring and autumn examinations: not one of them studies the way you do… If you don’t heed my advice, I shall have to leave you.’

For a while he did follow her advice. But as time went by he put it out of mind, and returned to his old bookish droning of texts. On one occasion he looked up for her, and she was gone. He called out despondently, beseeching her to come back, but she gave no sign. Then he remembered the place where he had first set eyes on her, and picking out his copy of the History of the Han Dynasty he turned to the very same page in the eighth volume, and sure enough there she was. He called to her, but she lay there motionless. He fell to his knees and entreated her to return. Finally she stepped down again from the book, saying to him:

‘If you ever ignore my advice again, I shall go, and this time it will be for ever.’

She told him to set out a Go-board and dice, and every day she invited him to play with her. But his heart was not in it. If she left the room for a moment, he would sneak out a book and start reading it. Afraid that she might find him out and disappear again, he secretly took the eighth volume of the Han History and concealed her hiding place from her in a jumbled pile of other books.

One day he was quite transported by his reading and failed to pay her any attention. All of a sudden he remembered her, and hurriedly covered up his book, but she had already vanished. In a great panic he began searching for her in every one of his books, but without any success. Finally he found her, folded once more between the very same pages of his copy of the Han History. He knelt before her and begged her to come back, swearing that this time he would never lose himself in his books again. She relented and stepping down once more, invited him to join her in a game of Go.

‘Over the next three days,’ she said, ‘you must improve your skill at playing Go, or I will have to leave you again.’

Three days later he succeeded in winning two pieces off her in a game. She was pleased with his progress, and now began to teach him how to play the seven-stringed qin. She gave him five days to master a certain melody. Lang concentrated for all he was worth on this new accomplishment, practising to the exclusion of all else. With time his fingers found their way into the rhythm, and he began to feel his whole body lilting to the music. Now she drank and played with him every day, and Lang was too happy to spare a thought for his books. She encouraged him to go out and make friends, and soon he acquired quite a reputation in society, as the life and soul of any party.

‘Now at last,’ she said, ‘you are ready to succeed in the examinations.’

One night he said to her:

‘Usually when a man and a woman live together, they have children. We’ve been together all this time. How is it that we still have no child?’

She laughed.

‘I told you,’ she said, ‘all that studying of yours, all those books, have been to no purpose. There’s one chapter you haven’t even begun to understand, the one on the Art of Love! I tell you, there are things you need to learn about in the bedchamber!’

‘Like what?’ he promptly asked.

She smiled and said nothing. But a little later she initiated him into that most intimate of Arts, and his joy knew no bounds.

‘I never knew that marriage could bring such a truly indescribable joy!’ he exclaimed. He went around telling everyone all about this latest discovery of his. His friends laughed at him behind his back, and Beauty chided him.

‘Surely,’ he replied, ‘it’s only when such things are done in secret and in a furtive manner that they should not be talked about. What is there to be ashamed of when they take place between husband and wife?’

Eight or nine months later, sure enough, Beauty gave birth to a son. They employed a nurse to take care of the infant. One day Beauty said to Lang:

‘I’ve been with you two years now, and I’ve given you a son. The time has come for me to leave. If I stay any longer, I fear it will only bring you misfortune, and we will live to regret it.’

Lang wept to hear these words. He threw himself down and would not rise up.

‘And what about our little one?’ he pleaded. ‘Will you not miss him?’

She herself seemed greatly distressed.

‘If you truly wish me to stay,’ she said, ‘then you must get rid of every book in your library.’

‘But the books are your very birthplace!’ he cried. ‘And they are my life’s blood. How can you make such a demand?’

She did not press him further.

‘Such is our fate then. But I had to warn you.’

During the past while, a number of Lang’s relations had caught glimpses of Yan, and had been amazed at how truly beautiful she was. No one knew anything of her story. She was a mystery. When they came in a body to question Lang about her, he was incapable of lying, and met their questions with total silence, which only increased their suspicions. Word of the matter eventually reached the ears of the District Magistrate, a young gentleman named Shi, native of Fujian Province, who had only recently passed his Doctor’s degree. He was now filled with an eager desire to see this Beauty for himself, and gave orders for both of them to be arrested. As soon as she heard of this, she vanished without trace, whereupon the Magistrate flew into a rage, detained Lang, stripped him of his Bachelor’s rank and had him put in the stocks and the cangue, in an attempt to extract from him the details of the girl and her whereabouts. But even when he was close to death, Lang refused to say a word. Their maidservant was also tortured, and she gave her version of the story, or the little she understood of it. The Magistrate concluded that Beauty must be some sort of evil spirit, and went to the house himself in a carriage, to carry out a personal inspection. He found the rooms piled high with books, far too many to search through, so he had them all burned. The smoke gathered in the courtyard, hovering over head in a dark cloud which would not disperse.

When Lang was finally released from detention, he travelled some considerable distance to obtain a letter from a former student of his father’s, as a result of which he was exculpated and reinstated in his official rank as a First Degree holder. In that autumn’s examinations he gained his Master’s degree, and the following spring graduated as a Doctor. But despite these successes, deep within him a bitter hatred still festered toward Magistrate Shi. He set up a little altar to Beauty, and prayed to her morning and night:

‘If you still have power, help me to be appointed an official in Fujian.’

A little later he was indeed posted as a Censor to Fujian, where he carried out a three month tour of inspection, during which he brought Shi’s various crimes to light, had him duly punished and his property confiscated.

At the same time sa cousin of his happened to be the local Prosecutor, and he persuaded Lang to take one of Shi’s favourite concubines to live with him, on the pretext of purchasing her as a maidservant. Once the matter of Magistrate Shi was settled, Lang resigned his post the very same day, and went home with this new concubine.

***

Parallel Text

Bibliomania 書痴

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

Lang Yuzhu of Pengcheng City in the province of Jiangsu was the son of a former Prefect, a scrupulous official who had used his salary not to amass personal wealth, but to build up a large private collection of books. His son was even more addicted to books than his father. The family lived in abject poverty, and were obliged to sell everything they possessed merely to survive. And yet, despite this, Lang refused to part with a single one of the books from his father’s collection. 彭城郎玉柱,其先世官至太守,居官廉,得俸不治生產,積書盈屋,至玉柱尤癡。家苦貧,無物不鬻,惟父藏書,一卷不忍賣。

The father had copied out in his own hand for his son’s edification, on a scroll to be hung by his desk, the words of the Song-dynasty Emperor Zhenzong’s ‘Exhortation to Learning’. Lang had the scroll covered with a protective length of white gauze, to save it from fading and from any other sort of damage. 父在時,曾書《勸學篇》黏其座右,郎日諷誦;又幛以素紗,惟恐磨滅。

[The words of the text were as follows:

A wealthy family has no need to buy rich lands,

Abundant grain is to be found in books;

No need of lofty halls,

Chambers of gold are to be found in books;

No need of household servants,

Carriage and horses throng the pages of books;

No need of a go-between,

In books are to be found beauties fine as jade.

Life’s goals can all be reached

Through diligent reading of the Six Classics.

當家不用買良田

書中自有千鍾粟

安居不用架高堂

書中自有黃金屋

娶妻莫恨無良媒

書中自有顏如玉

出門莫恨無人隨

書中車馬多如簇

男兒欲遂平生志

六經勤向窗前讀]

Lang did not strive to attain high office or to amass wealth. He genuinely believed that gold and an abundance of grain were to be found in books. To this end he studied earnestly night and day, enduring winter cold and summer heat. He reached the age of twenty without ever seeking a bride, in the sure belief that a beautiful woman would one day come to him of her own accord from within the pages of a book. When friends or relatives called, he was quite incapable of making ordinary conversation. After a couple of perfunctory remarks, he would start mumbling one of his set texts and his guests would sidle awkwardly out of the room. Whenever the Education Commissioner of the Province came on a tour of inspection, Lang always received the highest commendation. And yet, with all this bookish learning, he never once succeeded in passing either of his higher examinations, despite repeated attempts. 非為干祿,實信書中真有金粟,晝夜研讀,無間寒暑。年二十餘,不求婚配,冀卷中麗人自至。見賓親,不知溫涼,三數語後,則誦聲大作,客逡巡自去。每文宗臨試,輒首拔之,而苦不得售。

One day as he was deeply absorbed in his studies, a gust of wind blew the book from his hand. He hurried after it, and as he did so, the floor suddenly opened up before him. Upon investigation, he found that the cavity beneath the floor contained a mass of rotten grass. Digging it out, he could see that this had once served as a cellar for fodder, which had by now decomposed to form a sort of compost. It was no longer edible, but nonetheless he interpreted its very existence as corroboration of the words of the Exhortation: ‘Abundant grain is to be found in books’. As a consequence he applied himself still more diligently to his books. 一日方讀,忽大風飄卷去,急逐之,踏地陷足,探之,穴有腐草,掘之,乃古人窖粟,朽敗已成糞土。雖不可食,而益信千鐘之說不妄,讀益力。

On another day, he mounted a ladder to reach a high shelf and there, among a jumble of books, he came across a little golden carriage one foot long. In his joy, he took this too as proof of the words of the Exhortation: that ‘golden chambers, carriages and horses’ would ‘throng the pages of books’. When he showed it to a friend, however, the carriage turned out not to be made of solid gold, but merely gold-plated. He grumbled to himself that perhaps the Ancients had been trying to fool him. 一日,梯登高架,於亂卷中得金輦徑尺,大喜,以為「金屋」之驗,出以示人,則鍍金而非真金,心竊怨古人之誑己也。

A little while later, a fellow Bachelor-graduate and friend of his father’s, came on a tour as Circuit Intendant. This man was a devout Buddhist. It was suggested to Lang that he should present the gilded carriage to his friend as an ornament for his private shrine. The Intendant was greatly pleased, and gave Lang three hundred taels of gold and two horses in return. Lang was overjoyed, seeing in this indisputable confirmation of the Exhortation’s promise, not only of gold, but of a carriage and horses too. He resolved to be more bookish than ever. 居無何,有父同年,觀察是道,性好佛,或勸郎獻輦為佛龕。觀察大悅,贈金三百,馬二匹,郎喜,以為金屋車馬皆有驗,因益刻苦。

He was now thirty years of age. His acquaintances kept urging him to take a wife, to which his reply was always: 然行年已三十矣。或勸之娶,曰:

‘The Exhortation says that “beauties fine as jade” are to be found in books. Why therefore should I lament the lack of a beautiful wife?’ 書中自有顏如玉,我何憂無美妻乎。

And so he buried himself in his books for another two or three years, still with no success in his examinations. People began to mock him. At this time there was a popular saying going around, that the fairy-tale celestial lover, the Weaving Girl, had absconded from her starry home. His friends made fun of Lang, saying: 又讀二三年,迄無效,人咸揶揄之。時民間訛言天上織女私逃,或戲郎:

‘Perhaps it’s you the Heavenly Princess is coming to find!’ 天孫竊奔,蓋為君也。

Lang paid no heed to their taunts. 郎知其戲,置不辯。

One evening, he was absorbed in reading the History of the Han Dynasty and had reached the eighth volume, when, to his utter amazement, half way through the volume, inserted between two pages, he came across a silhouette of a beautiful lady, cut out of silk gauze. 一夕,讀漢書至八卷,卷將半,見紗翦美人夾藏其中,駭曰:

‘Can this really be the “beauty fine as jade” promised in the Exhortation,’ he mused to himself in great disappointment. 書中顏如玉,其以此應之耶。心悵然自失。

But when he looked more closely, it was as if he could see her eyes and eyebrows tremble into life. On the reverse side of the gauze were inscribed two tiny and barely legible characters: ‘Weaving Girl’. He marvelled greatly at this. Every day he placed the silk figurine on the cover of his book, and turned her over and over in his hand, deriving the greatest pleasure from simply gazing at her, so much so that he forgot to eat and was quite unable to sleep. One day, as he was thus occupied in his rapt gazing, the lady suddenly bent at the waist and rose. She seated herself on the edge of the book cover, and smiled at him. Lang started at the sight and fell to his knees before his desk. When he stood up, he saw that the lady had already grown to more than a foot in height. He was more astonished than ever, and fell at once to the ground again, knocking his head repeatedly on the floor. Gently she glided down from the desk and stood before him with an air of incomparable beauty and grace. 而細視美人,眉目如生,背隱隱有細字,云織女。大異之,日置卷上,反覆瞻玩,至忘食寢。一日,方注目間,美人忽折腰起,坐卷上微笑。郎驚絕,伏拜案下,既起,已盈尺矣。益駭,又叩之,下几亭亭,宛然絕代之姝。

‘Pray Madam Fairy,’ asked Lang, with a respectful bow, ‘will you tell me who you are?’ 拜問何神。

She smiled again. 美人笑曰:

‘My name,’ she replied, ‘is Yan Ruyu, which means Beauty Fine-as-Jade. You have known me now for some while. Day after day you have been gazing at me in rapture, and I had not come to you, there might never be another you in a thousand years, a man willing like you to have such unquestioning trust in the words of the Ancients.’ 妾顏氏,字如玉,君固相知已久。日垂青盼,脫不一至,恐千載下無復有篤信古人者。

Lang was overjoyed, and took her with him to bed. But although he embraced her warmly and affectionately, he had no knowledge of how to engage in what was expected of a man. 郎喜,遂與寢處,然枕席間親愛倍至,而不知為人。

From then on, whenever he was at his books, he asked her to sit by his side. She kept urging him not to study so hard, but he paid her no heed. 每讀,使女坐於其側,女戒勿讀,不聽。女曰:

‘It is because you study so hard that you always fail to pass the examinations,’ she insisted. ‘Just look at the roll of successful candidates at the spring and autumn examinations: not one of them studies the way you do… If you don’t heed my advice, I shall have to leave you.’ 君所以不能騰達者,徒以讀耳。試觀春秋榜上,讀如君者幾人。若不聽,妾行去矣。

For a while he did follow her advice. But as time went by he put it out of mind, and returned to his old bookish droning of texts. On one occasion he looked up for her, and she was gone. He called out despondently, beseeching her to come back, but she gave no sign. Then he remembered the place where he had first set eyes on her, and picking out his copy of the History of the Han Dynasty he turned to the very same page in the eighth volume, and sure enough there she was. He called to her, but she lay there motionless. He fell to his knees and entreated her to return. Finally she stepped down again from the book, saying to him: 郎暫從之。少頃,忘其教,吟誦復起,踰刻索女,不知所在,神志喪失,跪而禱之,殊無影跡。忽憶所隱處,取漢書細檢之,直至舊所,果得之,呼之不動,伏以哀祝。女乃下曰:

‘If you ever ignore my advice again, I shall go, and this time it will be for ever.’ 君再不聽,當相永絕。

She told him to set out a Go-board and dice, and every day she invited him to play with her. But his heart was not in it. If she left the room for a moment, he would sneak out a book and start reading it. Afraid that she might find him out and disappear again, he secretly took the eighth volume of the Han History and concealed her hiding place from her in a jumbled pile of other books. 因使治棋秤摴蒱之具,日與遨戲,而郎意殊不屬,覷女不在,則竊卷流覽,恐為女覺,陰取漢書第八卷,雜溷他所以迷之。

One day he was quite transported by his reading and failed to pay her any attention. All of a sudden he remembered her, and hurriedly covered up his book, but she had already vanished. In a great panic he began searching for her in every one of his books, but without any success. Finally he found her, folded once more between the very same pages of his copy of the Han History. He knelt before her and begged her to come back, swearing that this time he would never lose himself in his books again. She relented and stepping down once more, invited him to join her in a game of Go. 一日,讀酣,女至,竟不之覺,忽睹之,急掩卷,而女已亡矣。大懼,冥搜諸卷,渺不可得,既仍於漢書八卷中得之,頁數不爽,因再拜祝,矢不復讀。女乃下,與之弈。

‘Over the next three days,’ she said, ‘you must improve your skill at playing Go, or I will have to leave you again.’ 曰:三日不工,當復去。

Three days later he succeeded in winning two pieces off her in a game. She was pleased with his progress, and now began to teach him how to play the seven-stringed qin. She gave him five days to master a certain melody. Lang concentrated for all he was worth on this new accomplishment, practising to the exclusion of all else. With time his fingers found their way into the rhythm, and he began to feel his whole body lilting to the music. Now she drank and played with him every day, and Lang was too happy to spare a thought for his books. She encouraged him to go out and make friends, and soon he acquired quite a reputation in society, as the life and soul of any party. 至三日,忽一局贏女二子,女乃喜,授以絃索,限五日工一曲。郎手營目注,無暇他及,久之,隨指應節,不覺鼓舞。女乃日與飲博,郎遂樂而忘讀,女又縱之出門,使結客,由此倜儻之名暴著。

‘Now at last,’ she said, ‘you are ready to succeed in the examinations.’ 女曰:子可以出而仕矣。

One night he said to her: 郎一夜謂女曰:

‘Usually when a man and a woman live together, they have children. We’ve been together all this time. How is it that we still have no child?’ 凡人男女同居則生子,今與卿居久,何不然也。

She laughed. 女笑曰:

‘I told you,’ she said, ‘all that studying of yours, all those books, have been to no purpose. There’s one chapter you haven’t even begun to understand, the one on the Art of Love! I tell you, there are things you need to learn about in the bedchamber!’ 君日讀書,妾固謂無益。今即夫婦一章,尚未了悟,枕席二字有工夫。

‘Like what?’ he promptly asked. 郎驚問:何工夫。

She smiled and said nothing. But a little later she initiated him into that most intimate of Arts, and his joy knew no bounds. 女笑不言。少間,潛迎就之,郎樂極,曰:

‘I never knew that marriage could bring such a truly indescribable joy!’ he exclaimed. He went around telling everyone all about this latest discovery of his. His friends laughed at him behind his back, and Beauty chided him. 我不意夫婦之樂,有不可言傳者。於是逢人輒道,無有不掩口者。女知而責之。

‘Surely,’ he replied, ‘it’s only when such things are done in secret and in a furtive manner that they should not be talked about. What is there to be ashamed of when they take place between husband and wife?’ 郎曰:鑽穴踰隙者,始不可以告人;天倫之樂,人所皆有,何諱焉。

Eight or nine months later, sure enough, Beauty gave birth to a son. They employed a nurse to take care of the infant. One day Beauty said to Lang: 過八九月,女舉一男,買媼撫字之。一日謂郎曰:

‘I’ve been with you two years now, and I’ve given you a son. The time has come for me to leave. If I stay any longer, I fear it will only bring you misfortune, and we will live to regret it.’ 妾從君二年,業生子,可以別矣。久恐為君禍,悔之已晚。

Lang wept to hear these words. He threw himself down and would not rise up. 郎聞言泣下,伏不起。

‘And what about our little one?’ he pleaded. ‘Will you not miss him?’ 曰:卿不念呱呱者耶。

She herself seemed greatly distressed. 女亦悽然,良久曰:

‘If you truly wish me to stay,’ she said, ‘then you must get rid of every book in your library.’ 必欲留,當舉架上盡散之。

‘But the books are your very birthplace!’ he cried. ‘And they are my life’s blood. How can you make such a demand?’ 郎曰:此卿故鄉,乃僕性命,何出此言。

She did not press him further. 女不之強,曰:

‘Such is our fate then. But I had to warn you.’ 妾亦知其有數,不得不預告耳。

During the past while, a number of Lang’s relations had caught glimpses of Yan, and had been amazed at how truly beautiful she was. No one knew anything of her story. She was a mystery. When they came in a body to question Lang about her, he was incapable of lying, and met their questions with total silence, which only increased their suspicions. Word of the matter eventually reached the ears of the District Magistrate, a young gentleman named Shi, native of Fujian Province, who had only recently passed his Doctor’s degree. He was now filled with an eager desire to see this Beauty for himself, and gave orders for both of them to be arrested. As soon as she heard of this, she vanished without trace, whereupon the Magistrate flew into a rage, detained Lang, stripped him of his Bachelor’s rank and had him put in the stocks and the cangue, in an attempt to extract from him the details of the girl and her whereabouts. But even when he was close to death, Lang refused to say a word. Their maidservant was also tortured, and she gave her version of the story, or the little she understood of it. The Magistrate concluded that Beauty must be some sort of evil spirit, and went to the house himself in a carriage, to carry out a personal inspection. He found the rooms piled high with books, far too many to search through, so he had them all burned. The smoke gathered in the courtyard, hovering over head in a dark cloud which would not disperse. 先是親族或窺見女,無不駭絕,而又未聞其締姻何家,共詰之。郎不能作偽語,但默不言,人益疑,郵傳幾遍,聞於邑宰史公。史閩人,少年進士,聞聲傾動,竊欲一睹麗容,因而拘郎及女。女聞之,遁匿無跡,宰怒,收郎,斥革衣衿,梏械備加,務得女所自往。郎垂死,無一言,械其婢,略能道其髣髴。宰以為妖,命駕親臨其家,見書卷盈屋,多不勝搜,乃焚之,庭中煙結不散,瞑若陰霾。

When Lang was finally released from detention, he travelled some considerable distance to obtain a letter from a former student of his father’s, as a result of which he was exculpated and reinstated in his official rank as a First Degree holder. In that autumn’s examinations he gained his Master’s degree, and the following spring graduated as a Doctor. But despite these successes, deep within him a bitter hatred still festered toward Magistrate Shi. He set up a little altar to Beauty, and prayed to her morning and night: 郎既釋,遠求父門人書,得從辨復,是年秋捷,次年舉進士。而銜恨切於骨髓,為顏如玉之位,朝夕而祝曰:

‘If you still have power, help me to be appointed an official in Fujian.’ 卿如有靈,當佑我官於閩。

A little later he was indeed posted as a Censor to Fujian, where he carried out a three-month tour of inspection, during which he brought Shi’s various crimes to light, had him duly punished and his property confiscated. 後果以直指巡閩。居三月,訪史惡款,籍其家。

At the same time a cousin of his happened to be the local Prosecutor, and he persuaded Lang to take one of Shi’s favourite concubines to live with him, on the pretext of purchasing her as a maidservant. Once the matter of Magistrate Shi was settled, Lang resigned his post the very same day, and went home with this new concubine. 時有中表為司理,逼納愛妾,託言買婢,寄署中。案既結,郎即日自劾,取妾而歸。