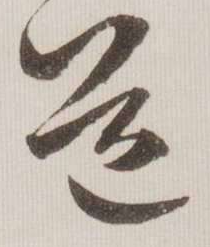

The Tao and the Power 道德經, attributed to Laozi 老子 (5th or 4th century BCE), is one of the most famous Chinese works. Previously, China Heritage has introduced chapters from a new translation of this classical text by John Minford. The full work, introduced, translated and annotated by John, appeared with Viking Random House in New York under the title Tao Te Ching — The essential translation of the ancient Chinese book of the Tao by Lao Tzu.

Previously, the translator has granted China Heritage permission to quote material from the introduction to his new version of what is a timeless work, as well as the first chapter of the translation — ‘Gateway to All Marvels’ 眾妙之門 — as well as the Florilegium, or Glossary. See: Tao Te Ching — a new translation of a Chinese classic, China Heritage, 20 November 2018.

The following essay first appeared in Words Without Borders on 8 December 2018 and we reprint it here with the author’s permission. The author would like to express his gratitude to Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom for introducing him to Words Without Borders.

The style of the original has been retained. In the quotations the original Chinese texts have been added, as have characters for names and terms where appropriate.

— The Editor

China Heritage

14 December 2018

Living with the Tao

John Minford

When the Oxford police arrested me in 1970, they thought that the battered copies of the Tao Te Ching on the back seat of my old Citroen 2CV were Maoist revolutionary pamphlets. It had, after all, been only a short while since the 1968 Maoist-inspired “events” of Paris. Decades later, I have had the opportunity to translate the ancient Chinese classic—while rambling from one place to another in Europe, Asia, and the Antipodes—and it has been one of the happiest experiences of my life as a sinologist and translator.

Ever since I began studying Chinese at Oxford in 1966, these eighty-one mesmerizing hymns have resonated in my mind, a silent a cappella choir singing across the ages. And although I had to wait half a century to feel even the slightest bit ready to undertake the daunting task of putting their silent music into English, during all of that time, the voice of the Tao has both comforted and haunted me, both challenged and sustained me.

As a teenage boy, I had sung twice a day in the Winchester College school choir (three times on Sundays), and through music and the chapel’s incomparable stained-glass window, I became drawn to the mysteries of the Christian faith. Eventually the music and the art proved stronger and more lasting than the faith. Decades later I read Robert Van Gulik’s treatise on music in Chinese culture, on the Tao of the Chinese lute, and it was a revelation. He quoted, among other things, the great poet, blacksmith, and musician, Xi Kang 嵇康:

Things prosper and decay

But Music never changes.

Music endures.

Tastes may satiate,

But Music never palls.

It guides and nurtures

Spirit.

It brings solace

To the wretched.以為物有盛衰,而此無變;

滋味有厭,而此不倦。

可以導養神氣,宣和情志。

處窮獨而不悶者,莫近於音聲也。

In this Taoist realm I found solace and some sort of home. I found myself in the company of kindred spirits from across the ages, most especially the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢, of whom Xi Kang was the most famous.

Translation itself, the transformation of ideas and words, whereby self and the other merge into one, can be a form of Taoist practice.

If translation has, above all else, to do with “hearing, or knowing, the sound,” what the Chinese call zhīyīn 知音, then the music of the Tao is the ultimate sound. It is the tiānlài 天籟, the Music of the Universe, and to listen to it, to hear it, and then to be foolhardy enough to attempt to translate it demands more than courage—it demands a deep exploration of silence. At the same time, to translate the Tao is to become gloriously part of a universal symphonic world. It has been a challenge, in my old age, that has taken me back to the heady 1960s and 1970s, when we were all young and idealistic—and when many of us did indeed mistake Mao for the Tao!

But mainly we all read Hermann Hesse, Alan Watts, Jack Kerouac, and Aldous Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy and Wilhelm’s I Ching. We took acid, we listened to Sergeant Pepper and Pink Floyd, we were all would-be Dharma Bums. The truth was we were all muddling along as best we could, making many of the same mistakes as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and George Harrison, sometimes with the same fatal consequences. “All things must pass,” and indeed they did, and most of what we thought we believed in passed only too quickly. Personal tragedies came our way. And yet, despite it all, the Tao remained with me: a soft silken fiber that could be used without end, a strand taking me back to Non-Being, through the noisy labyrinth to the light in an empty room.

Why was this? Why did it endure? How did it continue to provide an inexhaustible source of solace and peace? Wherein lay its Power? I am lost for words. No personal story of survival through times of grief or despair could ever hope to convey the elusive and yet constant truth that is the Tao and the Power. The great lover of flowers and wine, the poet Tao Yuanming 陶淵明, put it well:

On Drinking Wine

Day and night,

The mountain air is fine.

The birds fly back to their nests.

There is a deep meaning in this,

But try to explain it,

And I am lost for words.山氣日夕佳,

飛鳥相與還。

此中有真意,

欲辨已忘言。

To hold onto the Tao, to Embrace the One, requires no leap of faith. It is a matter of daily practice, daily living, whether that be one of the more structured practices—such as taijiquan, qigong, neidan alchemy, or plain jìngzùo 靜坐 (“sitting still”)—or something more casual, such as playing a musical instrument or singing. It could be a slow walk round a medieval cloister. Or a run on the beach with seagulls for company, as one of the greatest of all Taoist Masters, Master Lie 列子, once wrote: The song of the cicadas on a sun-drenched hillside can give access to the Tao. The French composer Paul Dukas said to his students: “Listen to the birds. They are great masters.” Hermits of ancient days practiced Taoist yodelling, a form of whistling that emulated the music of the Spheres. Translation itself, the transformation of ideas and words, whereby self and the other merge into one, can be a form of Taoist practice. The Tao can be lived in an infinite number of ways. My teacher Liu Ts’un-yan 柳存仁 once wrote: “If you are helping somebody to do charity work at a fête, you are a Taoist. If you watch birds or walk in the bush, you are a Taoist.”

Taoism has no catechism or creed. The Tao cannot be defined. Many Taoists have no notion whatsoever of being Taoists. They are not card-carrying members of any party or church. They are incognito, they conceal Taoist jade beneath anonymous garments of sackcloth. They often seem incredibly normal. Lao-Tzu 老子, the legendary Old Man, almost certainly never existed. There is no incarnation. There are no heretics.

Instead the Taoist lives according to a simple life-metabolism, a self-cultivation founded on matter-of-fact observations and realizations. The sun always declines from its zenith, the moon waxes only to wane, flowers bloom only to fade, the greatest joy turns to sorrow. We are born only to die. Taoism is a philosophy of gentle survival and acceptance. The Taoist, liberated from the smallness of the human Heart-and-Mind 心, takes refuge in the greater Heart-and-Mind of the Tao, surrenders to it in the spirit of what Taoists call Non-Action. The Tao blows like the Wind—everything dances before it. This sounds ridiculously simple, because it is, a simplicity understood by artists and musicians the world over. It is no more exclusively Chinese than the water that flows in the Yellow or Yangtze rivers. And Water is one of the prime symbols of the Tao.

Friendship is an age-old theme of Taoism, especially “predestined” friendship, the wordless sharing of Heart-and-Mind that suggests friendship from a previous lifetime, a shared experience of the Tao. Over the years, several friends have awakened me to this. A friend from Santa Fe, descended from a long line of New England transcendentalists, introduced me—more than fifty years ago—to the American-Indian art of New Mexico, and gave me a powerful Zuni fetish necklace, which I wear to this day. Another, a Zen cowboy-painter from Denver, Colorado, arrived unannounced at my Berkshire cottage in 1975 and stayed a whole year, playing his banjo and initiating me into the Taoist piano improvisations of Keith Jarrett.

When I began my Chinese studies, and made my first acquaintance of this ancient text, China was isolated in the madness of its Cultural Revolution. I first went to live in China years later, in 1980, at a time when the country was throwing off that madness only to embrace instead a stultifying materialism that has seemed to move it ever further from the Tao. And yet in the spring of 2016, when I returned to speak in public to young graduate students in Shanghai and Peking about my new translation of the ancient I Ching, which I had been working on since 2002, I was amazed by the eagerness of the young to discover, in an alien language, through translation into English, their own indigenous tradition of creative inspiration and freedom—their own Tao. There was a feeling of hope and excitement in the air.

The wonderfully generous Taoist spirit, the Hong Kong poet P.K. Leung 梁秉鈞, better known to his Hong Kong readers by his pen-name Yah See 也斯, twice came to visit me at Fontmarty, my old farmhouse in the hills of the Corbieres where I am writing these lines. He caught the essence of the place in a poem, inscribing it in a long lineage of lieux forts of the Midi. He saw it in the timeless light of the Tao, reading the lineaments of the surrounding hills according to the ancient art of fengshui:

House in the Valley

Here, in the vineyards of the Midi,

We sit together,

Outside in the courtyard

drinking tea…

At dusk I watch the last rays of the sunset

gild the hilltops beyond the garden wall…

The wise elders

Are there

Waiting for the rich harvest

to ripen on the wheel of time.

P.K. loved to laugh and he loved good wine, both in the best Taoist tradition. As Wang Ji 王績 wrote in the seventh century:

How long

Will this floating life

Endure?

How futile

The quest for Hollow Fame!

Better by far

A new vintage,

Another goblet downed

In the Bamboo Grove.獨酌

浮生知幾日,

無狀逐空名。

不如多釀酒,

時向竹林傾。

Throughout the ages, through periods of darkness and repression, China’s writers, artists, and free spirits, such as P.K., have held onto the Taoist core. The Tao Te Ching is the most ancient and powerful expression of that core. Its “mind-stretching qualities challenge at every turn, expanding our view of life’s possibilities.” The American sinologist Arthur Hummel wrote these words fifty years ago. The mantra-like hymns of the book have the power to help and heal both individuals and nations. “At a time when officials of particular nations on earth are vying to vaunt the ability of their leadership, or the merit of their incomparable power,” wrote the great scholar Anthony C. Yu 余國藩 in 2003, “even in the looming shadow of catastrophic conflict, the wisdom of the Tao Te Ching seems ever more compelling and urgent.” This is worth celebrating—this is surely a hymn worth singing, worth raising a glass to in the Bamboo Grove.

Fontmarty, lieu-dit Mato Caudo, Languedoc, July 2018

Also in China Heritage:

- ‘Tying Knots’ 結繩, the penultimate chapter of Tao Te Ching, trans. John Minford and quoted in The Year of the Rooster, On Reading, China Heritage, 15 January 2017; and,

- ‘Empty’ 沖, Chapter IV of Tao Te Ching, trans. John Minford and quoted in In the Shade 庇蔭, China Heritage, 4 April 2017

See also:

- John Minford, 易: A Cable into the Abyss of a Darker Time, The China Story Journal, 28 October 2015

- Geremie R. Barmé, On Heritage 遺, China Heritage, 1 January 2017