Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix IV

闔

In 1999, the restaurateur and cultural impresario Michelle Garnaut opened a new venture in Shanghai. M on the Bund 米氏西餐廳在上海外灘 was located in the Nissin Shipping Building on The Bund 上海外灘日清大樓七樓. It was Michelle’s first mainland venture, apart from having previously orchestrated a ten-day pop-up eatery at The Peace Hotel in December 1996. It followed on from M at the Fringe in Hong Kong, which she had established in 1989. In 2009, Michelle created Capital M in Beijing.

M on the Bund consisted of a restaurant, a bar, a lounge and a salon. Its reputation as a restaurant and a bar developed in tandem with the fame of its ambience and the cultural highlights that it offered. The expansive grace of its creator added to the al fresco delights of a terrace that offered striking views along The Bund and over to the Pudong megalopolis on the other side of the Huangpu River.

From 15 February 2022, M on the Bund will be no more. The theme of this modest tribute — our valentine to M on the Bund — is 闔 hé: a word-cluster that means variously the leaf of a door, to close a door and, by extension, to shut down an enterprise. For closure has been a feature of the Xi Jinping decade (2012-2022), whether it be in relation to China’s previously more commodious reform policies, prevailing attitudes to social change and political possibility or to cultural opportunity. The Xi decade has hastened the closing of the Chinese mind across the board.

***

***

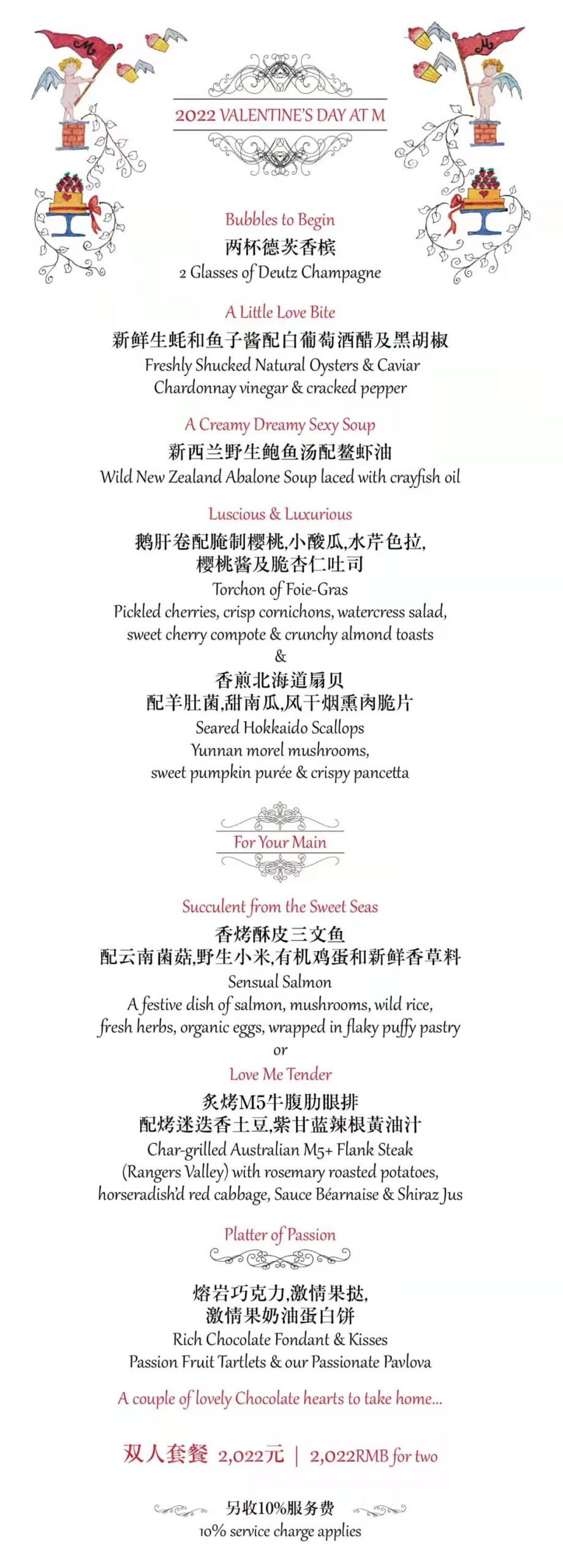

Over the years, Michelle Garnaut acquired a number of panoramic works by Lois Conner and they served to enhance the already distinctive style of M on the Bund. We are grateful to Lois for permission to use some of the work that she made at M itself and to Callum Smith, who kindly provided us with the restaurant’s Valentine’s Day menu and the 1996 announcement for M at The Peace.

This is Appendix IV in our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. It is also our valentine to Michelle Garnaut and the Lois Conner, two unique artists.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

14 February 2022

Valentine’s Day

***

Further Reading:

- The End of the Beginning 元宵, China Heritage, 11 February 2017

- Fionnuala McHugh, As Shanghai restaurant M on the Bund closes, what’s next for the woman behind the legendary venue that hosted royals, film stars and prime ministers?, South China Morning Post, 6 January 2022

***

From Jam Crêpes at The Peace Hotel

to Pavlova at M on the Bund

One of the few indulgences enjoyed by the handful of foreign exchange students at Shanghai’s Fudan University in the mid 1970s was late-night jam crêpes at the Peace Hotel 和平飯店, a landmark building on The Bund. The upper-story restaurant of what before 1949 had been the Cathay Hotel overlooked the Huangpu. In those days, apart from a mammoth sign in red neon on the Pudong side of the river that bellowed ‘All Hail Chairman Mao!’, the Cimmerian gloom of the vista was only punctuated by the feeble lights of passing boats. Previously, in 1966-1967, the radical Party theoretician Zhang Chunqiao had established his Shanghai base of operations at the hotel and it was from there that in the name of a thoroughgoing proletarian cultural revolution he encouraged Mao to ever greater political extremes. It was at the Peace Hotel that Zhang oversaw the founding of the Shanghai People’s Commune 上海人民公社. Inspired by the Paris Commune, Zhang and his supporters believed that this new political arrangement would not only transform the politics of Shanghai but China as a whole. Within weeks Mao ordered the commune disbanded and replaced with a ‘revolutionary committee’, which was his preferred model for centralised Party control.

Crêpes were among the few bourgeois fripperies that had survived those deadening waves of zealotry. (Another was Bombe Alaska, exclusive to the Red House 紅房子西餐廳 on the old Avenue Joffre in the former French Concession.) In the new millennium, my youthful memories of jam crêpes at the Peace were intermingled with the delights of pavlova and Turkish delight at M on the Bund.

***

***

It is five years since we bid farewell to Capital M, Michelle Garnaut’s base in Beijing overlooking Tiananmen Square (see Envoi for Capital M, 18 September 2017). At the time we remembered that luxurious venue as:

‘A place renowned for its cuisine, its relaxed elegance, the grace of its creator, the geniality of its staff, the excellence of its chefs, as well as for its cultural events and contributions to China in the world, Capital M also boasted unique views.

With those words we mourned the loss of a cosmopolitan salon in the heart of the People’s Republic. Even now we cherish memories of the riches that Capital M unstintingly offered to those who appreciated the possibilities of a China not crippled by parochial politics.

Like its sororal establishment in Beijing, M on the Bund was also a venue for literary and artistic events. In March 2017, six months before Capital M closed its doors, Michelle Garnaut invited me to participate in the annual Shanghai International Literary Festival. Addressing an audience in M’s salon, I launched the inaugural issue of China Heritage Annual, the theme of which was Nanking. The following day, I shared a stage with Timothy Garton Ash, a writer whose work I had admired for decades. At that event, my role was to introduce the speaker and his timely and valiantly defiant book Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World.

Rather than waxing nostalgic about jam pancakes at the Peace Hotel in my introductory remarks, I chose to dwell on the ever-increasing restraints on free speech under Xi Jinping. I did so by reminiscencing about my initial encounter with the circumscribed realm of Chinese speech in 1975. In particular, I focussed on how our group of foreign students at Fudan had come to learn about a famous literary feud that had taken place in Shanghai in 1925, exactly half a century earlier. The clash involved two of my favourite writers — Lin Yutang 林語堂 and Lu Xun 魯迅 — and it was the subject of one lecture in a semester-long course devoted to the study of Lu Xun who, because of Mao’s twisted appreciation, was one of the only pre-1949 writers to have survived the pervasive iconoclasm of the late 1960s.

The 1925 feud centered on the word 費厄潑賴 fei’e polai, itself a transliteration of the English term ‘fair play’. In late 1925, Lu Xun had mocked one of his enemies, a man who had supported the repression of student activism in Beijing, for being nothing better than a loathsome ‘pug’ 哈巴狗 and a lackey of the power holders. Lin Yutang whom, among other things, was known as a humorist had recently suggested that the literary scene was being increasingly befouled by excessive political rancor. In the hope of encouraging tolerance rather than acrimony Lin championed the spirit of 費厄潑賴 fei’e polai. Lin even suggested that such broad-minded forbearance should be extended to those who had thrown in their lot with the government of the day.

In a barbed response titled ‘Why “Fair Play” Should Be Deferred’ 論”費厄潑賴”應該緩行, Lu Xun responded by declaring that pugs were so smug that they were actually more like cats than dogs. In fact, they should be cast into the water and, as they struggled to get out, they deserved nothing less than a good beating. Only then perhaps, Lu Xun reasoned, would the playing field really be evened out. Although Lu Xun was merely indulging in his trade-mark penchant for exaggeration and vituperation, in this particular instance his caustic style and unforgiving tone found a ready home in the increasingly bitter politics of the day. In fact, over time, what was known as the combative ‘Lu Xun style’ would become a feature of polemical writing; both his work and his persona would eventually be so distorted by those who claimed his legacy on the left that, by the time we were studying in Shanghai in 1975, he had been sanctified as a cultural exemplar. Quotations from Lu Xun, handily taken out of context, even were regularly used to justify revolutionary violence.

In 1975, Lu Xun’s originally jocular expression 痛打落水狗, ‘beat a drowning dog with relish’, was a common short-hand used to justify the harsh and ongoing punishment of intellectuals and political figures purged and demonised from the 1950s through the 1960s. Lu Xun had mocked the pampered ‘pugs’ on the right of Chinese politics, but he had also warned people about the ‘mangy mutts’ 癩皮狗, or what Gloria Davies calls the ‘feral creatures on the left’. Perhaps mindful of the future, and a premonition as to the sordid posthumous role he would be forced to play in it, Lu Xun had declared that ‘a pack of well-fed mangy dogs will only run around and bark like mad. They are truly despicable.’ …養胖一群癩皮狗,只會亂鑽,亂叫,可多麼討厭! (from 半夏小集:七, trans. G. Davies).

Following my opening remarks, Timothy Garton Ash introduced the audience to what he had formulated as being the norms for ‘free speech in an interconnected world’. Among other things, Tim noted that the significance and history of free speech did not merely belong to ‘the West’, it had also long ago been appreciated in such distant climes as South Asia and ancient China. He even quoted a well-known Chinese saying dating from the Warring States period (475-221 BCE):

‘It is easier to damn a river than to silence people.’

防民之口 , 甚於防川。

At the time, in fact, this ancient expression was already being widely employed by Chinese writers from Beijing in the north (Xu Zhangrun 許章潤) to Hong Kong in the far south (Lee Yee 李怡). Indeed, long before March 2017, silencing discordant voices had been a defining feature of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. Even before Xi’s accession to power, Lu Xun’s own troubling outspokenness was being censored. In mid 2010, it was reported that his writings had been removed from high-school text books in Shanghai for being ‘too negative’.

Following our session at the Literary Festival that night, Michelle Garnaut joined Tim and me for dinner at the restaurant at M on the Bund. As we enjoyed an expansive prospect over to the day-glo lights playing on the skyscrapers of Pudong we finished our repast with pavlova, Turkish delight and coffee.

***

***

We concluded our Envoi to Capital M with an excerpt from a poem in Story of the Stone 石頭記, also known as The Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢, China’s most celebrated novel:

Mean hovels and abandoned halls

Where courtiers once paid daily calls:

Bleak haunts where weeds and willows scarcely thrive

Were once with mirth and revelry alive.

While cobwebs shroud the mansion’s gilded beams,

The cottage casement with choice muslin gleams….In such commotion does the world’s theatre rage:

As each one leaves, another takes the stage.

陋室空堂,當年笏滿床;

衰草枯楊,曾為歌舞場;

蛛絲兒結滿雕梁,

綠紗今又在蓬窗上。

亂烘烘你方唱罷我登場。

— ‘好了歌’,《石頭記》

from The Story of the Stone

trans. David Hawkes

***

A Loving Farewell Meal

***