Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix V

見

The arrival in Beijing of Richard Nixon on the morning of 21 February 1972 was the lead story on the ABC evening news in Sydney, Australia. (Note: the ‘ABC’ is the Australian Broadcasting Commission). A few days later I would head off to The Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. Two months shy of my eighteenth birthday I wanted to study Sanskrit and Tibetan in the university’s Buddhology Department. Classical Chinese would be my other major, although to study three-years of the classical language required a parallel major in Modern Chinese. From early March, I was studying with Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys). In the third term of the academic year, Dr Ryckmans took a leave of absence, starting in the third term of my first year at ANU. We subsequently learned that he had spent the time in Beijing.

In the preface to the English-language edition of Ombres chinoises (1974), the book in which he recorded his experiences, Pierre wrote:

‘Actually my book could be entitled The Unreal China. Unreal in two senses: first, because it deals in part with the stage settings artificially created in China for the use of foreign visitors, second, because like most other books on the People’s Republic it focuses not on the real life of real people (to which, alas! we have no access) but on the puppet theater of the Maoist gerontocrats, those wretched lead-and-cardboard bureaucrats who are mistaken for China’s driving forces when they merely weigh on it as its fetters. (In a way, Mao himself has finally become as irrelevant to China’s needs as Nixon to America’s—which might explain why the two gentlemen grew so fond of each other.)’

— Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows, Penguin Books, 1978, p.xix

***

In Australia, like most other places, Nixon’s Beijing trip was major news, although our own ‘China shock’ had come shortly before Henry Kissinger, the American president’s ‘China aide-de-camp’, had arrived in Beijing in July 1971. Just prior to that, Gough Whitlam, the leader of the opposition in the Australian Parliament, concluded his own visit to the Chinese capital during which he had made it clear that a government under his leadership would recognise the People’s Republic. So, although Nixon’s trip to Beijing might have been the story-of-the-day on 21 February 1972, for a Sydney teenager opposed to the Vietnam War and interested in China, Gough Whitlam’s had been the real news.

Shortly after winning office in late 1972, Whitlam withdrew Australian forces from Vietnam and established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. Cultural and educational exchanges soon followed, all part of what was called a ‘normalization’ of bilateral relations. As a result, and even before I completed my third year at university, I travelled to Beijing myself.

***

This is an essay in ‘1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China’, a joint miniseries in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium and Spectres & Souls — Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

28 February 2022

***

1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China

- 嘩 — The Coups of 1971

- 見 — A storied Handshake, an excised Interpreter & a muted Anthem

- 撼 — A Week That Changed The World

- 蒞 — Nixon’s Press Corps

- 迓 — ‘Welcome to China, Mr. President!’

- 迥 — Dissing Dissent

- 鞭 — The President & The Chairman in Retrospect

- 書 — A 2012 Letter to the Chinese Embassy

***

Related Material:

- ‘Nixon In China Itinerary, Feb. 17-28, 1972’, excerpted from ‘Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents’, 28 February 1972

- The Week that Changed the World: The Inside Story of Richard Nixon’s 1972 Journey to China, USCI/Nixon Foundation/Nixon Center symposium, 10 November 2010

- ‘Getting To Beijing: Henry Kissinger’s Secret 1971 Trip’, USC U.S.-China Institute, 21 July 2011

- ‘Getting To Know You — The US And China Shake The World, 1971-1972’, USC U.S.-China Institute, 21 February 2012

- The Editor, ‘Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Washington’, China Heritage, 14 May 2020

- Chas W. Freeman, Jr, ‘The State of the Sino-American Pas de Deux in 2021’, China Heritage, 20 February 2021

- Jane Perlez & Scott Tong, ‘The Great Wager’, a five-part series, Here & Now, 8 February 2022

- ‘Similar Nightmares, Different Dreams’, USC U.S.-China Institute, 17 February 2022

- Winston Lord, interviewed by Bernhard Zand, ‘A Half Century after Nixon’s Visit to China: “Xi Is, Along with Putin, the Most Dangerous Man in the World” ’, Spiegel International, 22 February 2022

Documents:

- Nixon announces trip, 1971

- Mao and Nixon Meet, 1972

- Shanghai Banquet Toasts, 1972

- Shanghai Communiqué, 1972

- Nixon, Upon Return, 1972

— reproduced from 撼 — A Week That Changed The World

三世:有見有聞有傳聞

There are Three Ages of Man:

The Age that one witnesses for oneself;

A Prosperous Age that one hears about; and,

The Legendary Age of Perpetual Peace.

— Dong Zhongshu, Elaborating The Spring and Autumn Annals

董仲舒《春秋繁露·楚莊王第一》

***

News Has a Kind of Mystery

— Excerpt from the final dress rehearsal of John Adams’

‘Nixon in China’ at the Met Opera, 31 January 2011

***

The Handshake, an Interpreter and the Anthem

Watching the evening news on 21 February 1972, three things stood out: the first was Richard Nixon’s anxious demeanor as descended the mobile airstairs reaching out to shake Zhou Enlai’s hand; the second was the interpreter standing at a discreet distance on Zhou’s righthand side; and, third, the Chinese National Anthem which struck up as the two leaders reviewed the honour guard.

I would not appreciate the significance of the handshake or the controversy surrounding the interpreter for some years, although it was not long before I learned about the troubled history of China’s anthem.

***

***

A Bespoke Handshake

The Nixon-Zhou handshake has been a point of debate for decades. ‘Anxieties about the handshake were not trivial,’ wrote a later commentator.

‘Aides responsible for the optics of the visit pointed to an incident in Switzerland years before when then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles refused to shake Zhou’s hand, reportedly telling aides that they would only meet in a car crash. Nixon … saw the handshake as a talisman for the entire visit. A cold shoulder would signal doom for Nixon’s high hopes.

‘When the time came, he reached for Zhou’s hand and received a hearty clasp in response.

‘Prior to the shake seen around the world, Nixon fretted over the TV coverage, writing in his memoirs that a “picture is worth 10,000 words.” ‘

— Doug Barry, ‘The Handshake that Changed the World’

China Business Review, 21 February 2019

Later that same day, the subject of the handshake would come up again:

Memorandum of Conversation, Monday, February 21, 1972 – 5:58 p.m.-6:55 p.m.

Plenary session during which Nixon and Zhou agreed on meeting arrangements: high level Nixon-Zhou talks on “basic matters” and meetings between Secretary of State Rogers and Minister of Foreign Affairs and their “assistants” on steps to promote normalized relations, trade, and scientific-cultural exchanges. One highlight is Zhou’s recollection of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’s refusal to shake hands at the Geneva Conference in 1954. Zhou further recalls that Undersecretary of State Walter B. Smith did not want to “break … discipline” but also did not want to slight the Chinese so blatantly. Therefore, Smith held a cup of coffee in his right hand and “used his left hand to shake my arm.”

— from Record of Historic Richard Nixon-Zhou Enlai Talks in February 1972 Now Declassified. For an extended version of these materials, see: William Burr, Nixon’s Trip to China’ (Records now Completely Declassified, Including Kissinger Intelligence Briefing and Assurances on Taiwan), National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 106, 11 December 2003

Ji Chaozhu (冀朝鑄, 1929-2020), Zhou Enlai’s interpreter, who was present at the Geneva Conference in 1954, offers the following:

‘The Americans were the last to arrive that day, led by a tight-lipped, hawk-nosed John Foster Dulles, the secretary of state. A true American patrician, Dulles, sixty-six, was a Princeton man who took his law degree at George Washington University. He had gone on to become a partner at a prestigious Wall Street firm, Sullivan & Cromwell. Dulles’s grandfather and an uncle had both been secretaries of state, and his younger brother was Eisenhower’s director of Central Intelligence.

‘Dulles was the reactionary’s reactionary, with a reputation for dealing with Communists as if he were killing snakes. He made the rounds, shaking hands with Eden, Mendès France, and Molotov. As Dulles turned to leave the Soviet delegation, the premier pivoted to face him, smiled, and brought up his hand. But Dulles darted back across the room, aides in tow.

‘The Chinese delegation watched this little drama with indignant stares. But the premier just shrugged slightly and calmly turned back to the group. He gestured with his hand, as if to say, “It’s nothing, forget about it.” It was not the first time he had come face-to-face with American bad manners. He had been at the airstrip in Yan’an the day General Hurley dropped in on Mao and uttered his infamous Choctaw war whoops.

‘A few days later, we learned that Dulles had issued instructions to his staff that no one, under any circumstances, was to shake hands with any of us “goddamned Chinese Reds.” Like General Harrison in Panmunjom—with his whistling and impatient finger-tapping—Dulles played a tough guy.

‘Although Premier Zhou shrugged it off, this insult resonated in a way that no other could. The People’s Daily featured the incident prominently in its coverage of the conference, declaring it a clear sign that the Americans meant to do China harm. The episode of the unshaken hand would become a legend in our foreign affairs, poisoning our relations with the United States for nearly two decades.”

— Ji Chaozhu, The Man on Mao’s Right: From Harvard Yard to Tiananmen Square,

My Life Inside China’s Foreign Ministry, New York: Random House, 2008, pp.260-261

***

The Excised Interpreter

‘… it began on the cold gray morning of February 21, 1972, when Air Force One landed at Beijing Airport. The crowd was small: about two dozen of our officials and a bank of television cameras, photographers, and reporters. However, the entire world was watching, live, on television.’

So starts the account of that day in The Man on Mao’s Right, the interpreter Ji Chaozhu’s memoir quoted above. He goes on to write:

‘Kissinger had previously acknowledged regret at the old Dulles insult in Geneva, and Nixon was anxious to create a new, hopeful symbolic moment. The plane taxied to the welcoming area and the door opened. Nixon emerged alone. He had instructed his entire delegation, including Mrs. Nixon, to hold back until he had deliberately and enthusiastically shaken the hand of Premier Zhou Enlai.

‘I stood just behind the premier, on his right, as Nixon said, to the best of my recollection, “This hand stretches out across the Pacific Ocean in friendship.” Nixon later wrote, “As our hands met, one era ended and another began.”

‘The premier replied, “China welcomes you, President Nixon,” and asked about his flight. Then the First Lady was introduced and the rest of the Nixon entourage came down the stairs. The official visit was under way.

‘The next day, in newspapers around the world, the moment was memorialized on front pages, with me leaning toward the premier’s ear. (The sound of the jet engines had made it difficult to hear what was being said.) In one of those absurd turns of Chinese politics, the photo was altered for the Chinese press; I was airbrushed out of the picture, and where I had been standing there was Wang Hairong [王海容]!’

— Ji Chaozhu, The Man on Mao’s Right: From Harvard Yard to Tiananmen Square,

My Life Inside China’s Foreign Ministry, New York: Random House, 2008, pp.501-503

Wang Hairong was Mao’s niece. In his biography Ji Chaozhu repeatedly refers to Wang and Nancy Tang (a figure who inspired Gary Trudeau to create the character ‘Honey Huan’) — a colleague whom Ji had recommended to the Chinese Foreign Ministry on the basis of her English ability and the fact that she had been a family friend in New York in the 1940s — as the ‘Two Young Ladies’. Canny players in the factional politics of the day, more often than not Wang and Tang carried out the wishes of Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife and a prominent figure in the anti-Western camp.

In regard to being airbrushed out of the historical record on the Chinese side, Ji curtly observed that ‘the two young ladies had been busy.’

***

***

In his review of Ji Chaozhu’s biography in The New York Times, David Barboza wrote that ‘there was … a Zelig-like quality to Mr. Ji’s life’:

‘Because he served for more than 20 years as an English-speaking interpreter for China’s leaders, Mr. Ji turns up in numerous historic photographs: on the Tiananmen rostrum in 1971 with Chairman Mao Zedong and the American journalist Edgar Snow (a subtle hint that China sought improved relations with the United States); with Mao and his last official visitor, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, in 1976; and helping Deng Xiaoping don a white cowboy hat during his whirlwind tour of the United States in 1979, which included a visit to a Texas rodeo.’

Although the Nixon visit was one of the high-points of Ji’s career, due to the infighting of the time, Jiang Qing’s animus and the jealousy of the ‘Two Young Ladies’, he was banished to plant rice and haul manure in the Shanxi countryside so that he might tame his bourgeois arrogance and erroneous thoughts. As Barboza notes,

‘Mr. Ji was rehabilitated in 1972, when Mr. Zhou asked: “Where has Little Ji gone? I need him!” He was sent to the countryside again, and then back to the leadership compound, part of the bizarre power struggles that shook the leadership compound in the Mao era.’

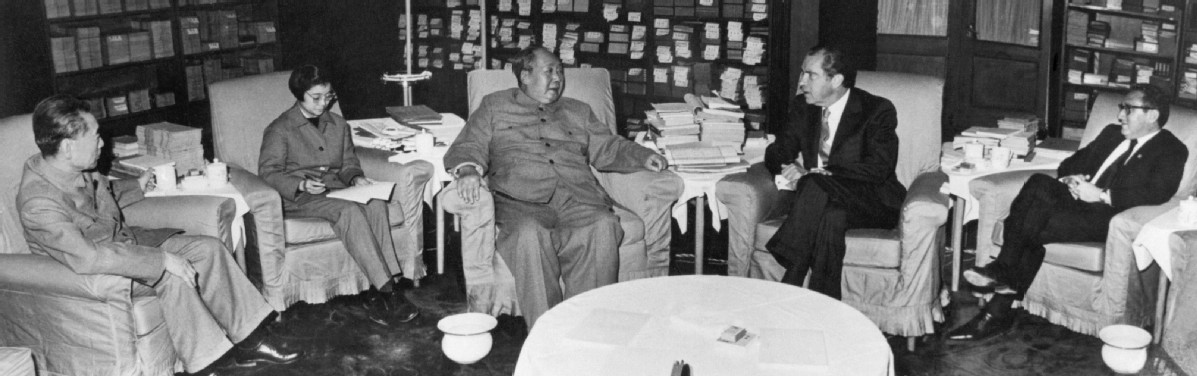

On Nixon’s side, the Americans practiced some legerdemain of their own. Winston Lord was present at the Mao-Nixon meeting at Zhongnanhai held on the afternoon 21 February 1972. At the time, the official photograph of the occasion was cropped so as to excise Winston Lord, Henry Kissinger’s personal assistant, who had been sitting to Kissinger’s left—so as to lessen the anticipated annoyance of Secretary of State William Rogers, whom Kissinger had excluded from the meeting.

***

A Muted Anthem

Some years before the Nixon trip, Samson Voron, my classmate at Randwick Boys’ High and a ham radio enthusiast had introduced me to the stentorian broadcasts of Radio Peking. I had become familiar with ‘Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman’, the ‘anthem’ of the Cultural Revolution era, and ‘The Internationale’ sung in Chinese. ‘The East is Red’ was the provisional national anthem of China having replaced ‘The March of the Volunteers’ 義勇軍進行曲. Composed by Nie Er, a musician who had died in the 1930s, the lyrics of that anthem were the work of Tian Han (田漢, 1898-1968). Although as early as 1930, Tian had pre-empted attacks on him by publishing a long self-criticism titled ‘We Denounce Ourselves’ 我們的自己批判 in 1930, as a prominent cultural figure in ‘New China’ the Red Guards did not spare him. Vilified, denounced and beaten repeatedly, he was eventually jailed and died a broken man in 1968. Although ‘The March of the Volunteers’ remained on the books, it was rarely played and its lyrics were outlawed.

On the occasion of the Nixon visit in February 1972, however, after the PLA orchestra at the military airport that was used for the greeting ceremony had played ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, it struck up the old anthem. Perhaps Zhou Enlai and others had felt that ‘The East is Red’ lacked the gravitas required for the occasion (see ‘The East is Red Transformation of a Love Song’).

(‘The March of the Volunteers’, originally written for a 1935 film, was adopted as the provisional national anthem in 1949, its status being reaffirmed in 1959 at the time of the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The Cultural Revolution-era ban on Tian Han’s lyrics were lifted in 1983, although they were re-written. The Nie Er-Tian Han composition was formally adopted as the national anthem in 1984 and, in March 2014, its status was affirmed by a revision to the Chinese Constitution.)

***

中華人民共和國國歌

起來!

不願做奴隸的人們!

把我們的血肉,築成我們新的長城!

中華民族到了最危險的時候,

每個人被迫著發出最後的吼聲。

起來!

起來!

起來!

我們萬眾一心,冒著敵人的炮火,

前進!

冒著敵人的炮火,

前進!

前進!

前進!進!

Lessons for Today?

‘Nixon stayed in China for a seven-day televised spectacular brought live into American living rooms. America’s network news anchors trailed Nixon to the Great Wall, to banquets where he spoke glowingly of the new rapprochement, to a lake in Hangzhou where he fed goldfish. When he got home, his ratings in the polls had soared by seven points. Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, joked that Nixon’s trip should be a pilot for a television series.

‘After his resignation in disgrace, Nixon kept a constant interest in China. He visited Mao before he died in 1976. But he had few illusions that China would become democratic: that goal was for sentimentalists. And he intuited that his achievement in prying China away from the Soviets could eventually end up to America’s disadvantage. He could see that China would catch up with the US militarily and economically.

‘His biographer, Richard Reeves, recalled that Nixon believed there would eventually be conflict between the US and China, and in that situation, the outlook for the US was grim.

‘ “It might be a shooting war. It might be an economic war,” Reeves told an audience at the John F Kennedy Library in Boston in 2006. “But their interests were fundamentally different over the long term. And, eventually, they would clash.” It was up to his successors, Nixon believed, and the job of the leaders of the west to prevent that from happening, or prevent that for as long as possible, Reeves said. “The east would win that confrontation,” was Nixon’s assessment.’

— from Jane Perlez, ‘Nixon in China: are there lessons for today’s leaders?’

Financial Times, 11 February 2022

***

Peace Duck Tang on Air Force One, Richard Nixon and Du Xiuxian

***

- Tang Shizeng (唐師曾, 1961-) is a retired photojournalist, author and blogger known for reporting for Chinese state media on conflicts in the Middle East. For Tang’s YouTube channel, see 唐和尚Peaceducktang