Spectres & Souls

In the northern summer of 2018, a spark from a rancher’s steel hammer pounding on a rusty stake in a bone-dry field ignited the largest wildland fire in the history of California. After recounting how the Ranch Fire blaze devastated Mendocino County, California, in the introduction to his Wildland: The Making of America’s Fury (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021), Evan Osnos writes:

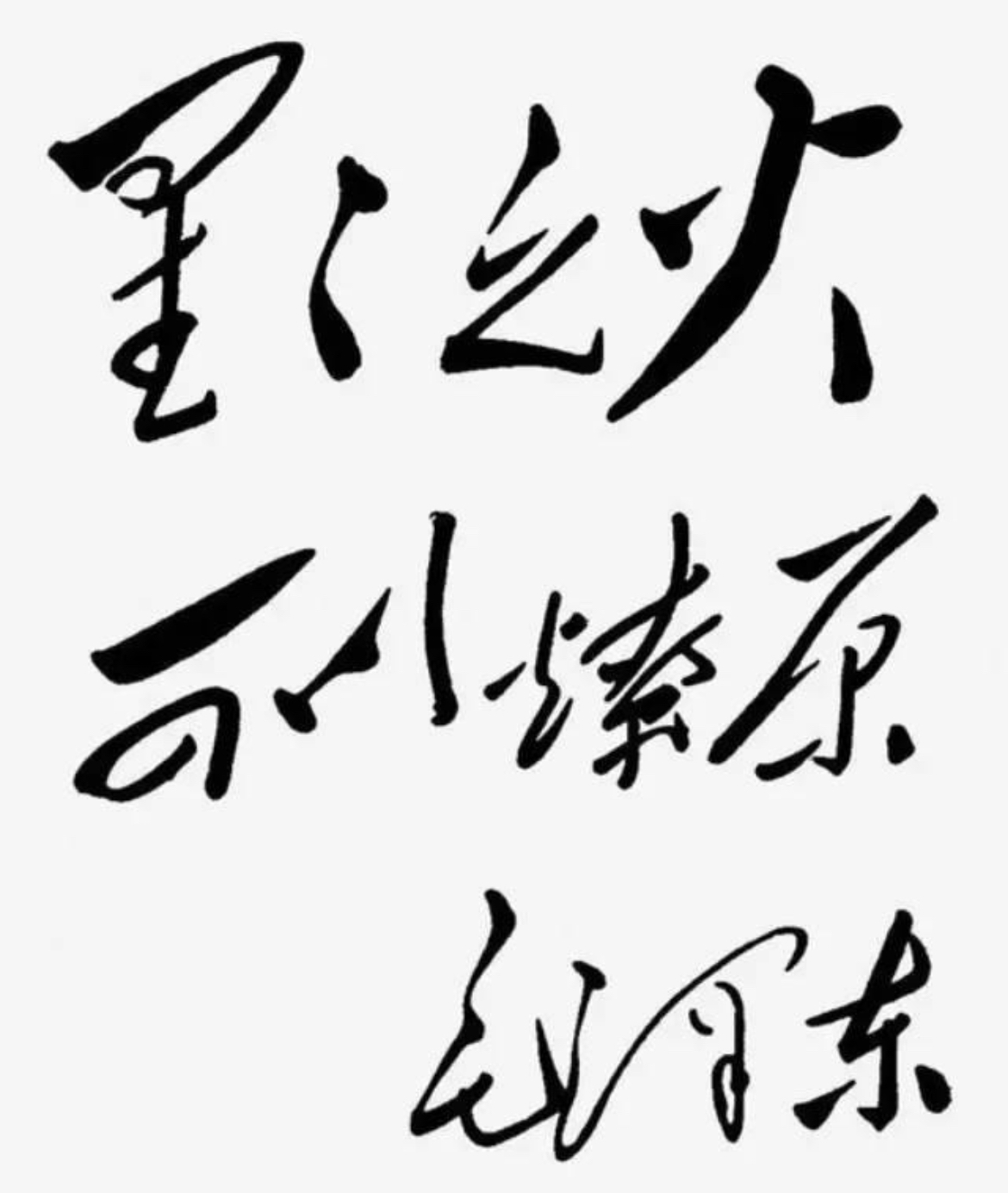

‘That story reminded me of an old line about politics, from a book by the Chinese revolutionary Mao Zedong. “A single spark,” Mao wrote, “can start a prairie fire.” Mao knew little of America, but he knew brutal truths about politics. Living in Washington in the years of Donald Trump, I often thought about that image of a landscape primed to burn. Sometimes it felt like metaphor, and sometimes it felt like fact. But eventually I came to understand it as something else—a parable for a time in American history when the land and the people seemed to be mirroring the rage of the other. I wanted to understand how that time had come to be, and what it would leave behind.’

— Osnos, Wildland, p.4

Weaving together his reporting career, family history and contemporary events Osnos offers a meditation on America today as well as on the post-Cold War West. As he notes, as early as 1992, Francis Fukuyama had cautioned that during a period of relative respite people could well chose to ‘struggle for the state of struggle. They will struggle, in other words, out of a certain boredom: for they cannot imagine a world without struggle’ (Wildland, p.316).

Spectres & Souls: China Heritage Annual 2021 is subtitled ‘Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021’. In chapters published through 2021 and 2022, it attempts to offer some glimpses into and reflections on the struggles that have characterised the last 160 years. In disparate ways they inform and predict how the contestation within the global powers that dominate the twenty-first century and the conflict between them touches on all of those dragged, willingly or unwillingly, into their thrall. It is a landscape primed to burn, as Osnos says of the United States: this is both a metaphor and a fact.

***

***

I had followed Evan Osnos’s reporting on China from the time that he was posted to Beijing by The New Yorker in 2008. I was particularly taken with him when he wrote a comment on the vexatious litigation surrounding ‘The Gate of Heavenly Peace’, a 1995 documentary film which I co-wrote with John Crowley. I was also the main author of the film’s accompanying website.

In ‘The American Dream: The Lawsuit’, a report published in the lead up to the twentieth anniversary of June Fourth in 2009, Osnos said:

‘Having graduated from Princeton and Harvard, Chai (who now goes by Ling Chai) is now the President and Chief Operating Officer of Jenzebar Inc., a maker of educational software. She is reportedly suing The Long Bow Group, the nonprofit film group behind “Gate of Heavenly Peace,” claiming that a Web site accompanying the film infringes on Jenzabar’s trademark. According to an account of the lawsuit in the Times of London, “A court has already dismissed a defamation suit brought by Ms Chai. The claim that the film-makers are infringing trademark by mentioning Jenzabar on their website also looks unlikely to succeed, according to court statements.” Rather, the filmmakers accuse Chai of trying to shut them down with legal bills. They say her company’s lawsuit accuses them of being “motivated by ill-will, their sympathy for officials in the Communist government of China, and a desire to discredit Chai….”

‘For the record, to anyone with knowledge of the film, the notion that it is sympathetic to the Chinese government is laughable. But, whatever happens with the suit, it’s hard to imagine a more acute measure of how far the student movement has faded into memory. Or, how much it’s been replaced by more practical priorities. Chai’s company’s Web site lists its corporate mission as helping to create a “gateway to the American dream.” ‘

The following year, I began putting together a modest glossary of Chinese terms for China Heritage Quarterly, inspired in part by the tenuous connection between a novel by the Hong Kong writer Chan Koon-choong, the long-dead essayist Lin Yutang and Evan Osnos in Beijing. Writing a decade before the expressions ‘lying flat’ 躺平 and going ‘inverted’ 内卷 became popular in 2020-2021, I said:

‘A more immediate origin of the Glossary stems from the need to formulate a translation for the expression “houzheteng shidai” 后折腾时代 used by Chan Koon-chung 陳冠中 in his 2008 In an Age of Prosperity: China 2013 (《盛世:中國、2013年》; an English version of the novel appeared in 2011 under the title The Fat Years). In formulating a term to convey some of the sense of zheteng, I wrote the following:

Zheteng 折腾 / 折騰

‘No single English word or expression can adequately convey the cluster of meanings inherent in zheteng. For “to zheteng” is to be unsettled, to struggle, to get by, to try and achieve something but possibly to fail to do so. It means to be exasperated but to battle on regardless. It is to engage with the world uneasily, to sit uncomfortably and to annoy others/oneself/the system/the status quo by one’s tireless squirming and restlessness. It is to buck the system, but to believe nonetheless that all resistance is futile; it is to rage against the dying of the light, but to have no confidence that there was any light or that the impending gloom is really all that bad. It is to be ill-at-ease and, by one’s efforts, to make others feel the same way. When Linda Jaivin was writing her review of Chan Koon-chung’s 2008 novel In an Age of Prosperity: China 2013 (陳冠中著 《盛世:中國、2013年》) for China Heritage Quarterly, I suggested that she translate the expression “houzheteng shidai” 后折腾时代 that he used to describe China’s near future as the “Age of Complacency”, that is, a time when people have found that the struggles and ventures of the 1980s, be they meaningful or merely vacuous performances, are spent and that an era of quietude, a time after zheteng now reigns supreme. With energy spent and wills weakened, all that people have to console themselves with is impotent complacency. They find themselves in a time when even to zheteng is nugatory—houzheteng shidai 后折腾时代. Middle-age world-weariness awaits senescence.

‘In December 2008, the Party General Secretary Hu Jintao called for his comrades to pursue an approach encapsulated in terms of what were called the “Three Don’ts”: 不动摇, 不懈怠, 不折腾 (bu dongyao, bu xiedai, bu zheteng). Writing for Danwei, Joel Martinsen noted that the official translation of the “Three Don’t’s was ‘don’t waver, don’t slacken, don’t get sidetracked’ ” (from Joel Martinsen, “Interpreting the Wisdom of Hu Jintao”, Danwei, 31 December 2008). Given the preceding paragraph related to the cluster of meanings attached to zheteng, one could also suggest “sit still!”, “keep focused”, or even “don’t fiddle”.

‘Not long after my note on zheteng appeared in the June 2010 issue of this journal, the China correspondent for The New Yorker, Evan Osnos, chose to call his regular online Letter from Beijing “The Age of Complacency”. In that virtual letter dated 28 July 2010 Evan, winsome as ever, decided to quote my definition of houzheteng shidai in full, calling this wordy attempt to come to grips with the expression zheteng an “heroically detailed footnote”. This serendipitous New Yorker connection brought me back to Lin Yutang, a man who in 1930s Shanghai founded a number of urbane literary journals that he modeled along the lines of The New Yorker, or Niuyue Ke 紐約客 as it is known in Chinese.

A decade later — in ‘The Good Caucasian of Sichuan & Kumbaya China’ (China Heritage, 1 September 2020) — I had an opportunity to comment further on the connection between Lin Yutang and The New Yorker, this time bringing Peter Hessler and Xu Zhangrun ‘into the conversation’. By that stage, China’s ‘age of complacency’ had been shunted aside by Xi Jinping’s relentless pursuit of the ‘philosophy of struggle’ 鬥爭哲學. Now, the American world of struggle that Fukuyama had speculated about in 1992, and which Evan Osnos chronicled in Wildfire, was in dialectical sync with that of the People’s Republic of China.

***

In the following excerpt from Wildland, reprinted with the tweet that set off Evan Osnos’s reflections as a chapter in China Heritage Annual 2021: Spectres & Souls, the connection is Hannah Arendt and ‘Truth and Politics’, an essay that appeared in the pages of The New Yorker in February 1967. It is hardly coincidental that Xu Zhangrun, the noted legal scholar becalmed in Beijing, often quotes Arendt.

My thanks to Evan for his kind permission to reprint this material and apologies for what some may regard as being my inapposite contextualisation of it.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 November 2021

***

Further reading:

- ‘The Invisible Republic of the Spirit — Preface to Spectres & Souls’, China Heritage, 18 January 2020

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, ‘Living Lies in China Today’, China Heritage, 8 May 2019

- Leonard Cohen, ‘Democracy & The Future — 3 November 2020’, China Heritage, 3 November 2020

- Isaiah Berlin, et al, ‘Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic’, China Heritage, 10 June 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Vacláv Havel, ‘History as Boredom — Another Plenum, Another Resolution, Beijing, 11 November 2021’, China Heritage, 14 November 2021

***

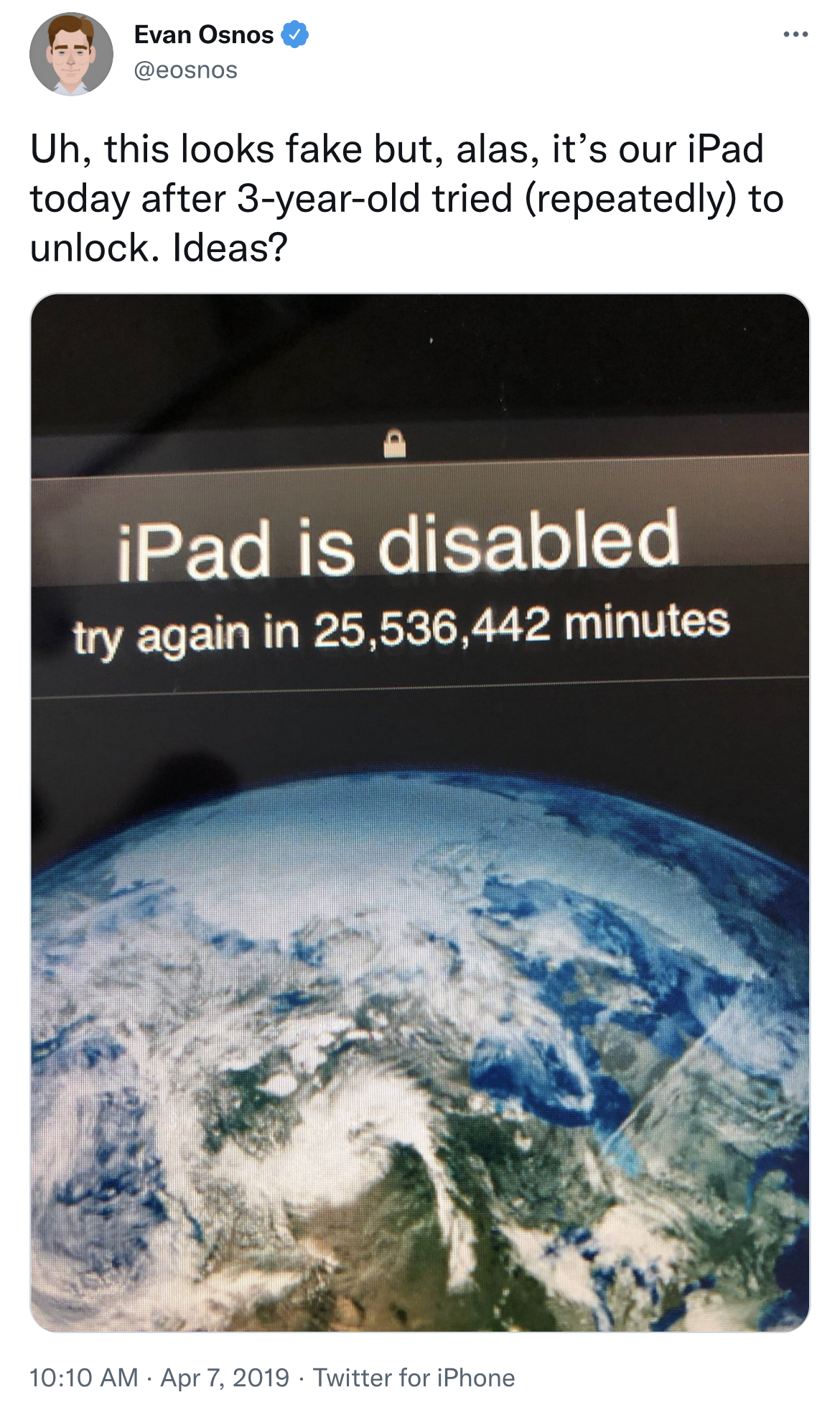

At home on a Sunday in 2019, I went looking for the iPad that we used for watching movies—and for distracting kids on car trips. Ollie, who was three, loved the iPad, no surprise, and whenever he got ahold of it, he entered random numbers into the passcode screen to try to unlock it. When I found it that afternoon, Ollie had made an especially diligent run at it. It wasn’t clear how many codes he had tried, but by the time he gave up, the screen said “iPad is disabled, try again in 25,536,442 minutes.” That worked out to about forty-eight years. I took a picture of it with my phone, wrote a tweet asking if anyone knew how to fix it, and went downstairs to dinner.

I didn’t think much about the iPad again until the next morning, when I received an email from the news division of CTV, a Canadian television network, asking for information about “the locked iPad.” Three minutes later, another email arrived, this time from the Daily Mail Online, in London. I ignored them. Soon I was hearing from CNN and USA Today. A British friend sent a text of condolences on the locked iPad and a screenshot of another article headlined “LOCK SHOCK: Baffled dad locked out of iPad for 25 million minutes after son, 3, tried to guess password.” (It was featured beside pregnancy photos of Meghan Markle.)

When I went online, I discovered that the tweet had taken flight and generated thousands of reactions. Some people were scolding: “I wonder why a 3yo is in reach of an iPad. Deserved this tbh.” Others were heartfelt: “Obviously, your offspring has the dogged, unfailing persistence required for a future career in a research field.” But I was intrigued, above all, by a subset of readers who had scoured the photo like the Zapruder film and pronounced it a conspiracy or a fraud: “Its display is not Retina and the wallpaper is from the first iOS series,” someone wrote. “Great work of deceiving people!”

I contacted the guy who wrote that—a Pakistani teacher named Khalid Syed—and he was happy to chat. “Sorry for my terrible English, he said. He and friends had seen the story about my iPad on CNN and suspected it was corporate dark arts by rivals of Apple. Or maybe, he suspected, “you want to be popular on Twitter.” He said, “People are so after money. And can do anything to get money. I have seen it.”

The emails and tweets kept arriving for several more days. The more I read, the more they reminded me of what Hannah Arendt called a “peculiar kind of cynicism” that settles into societies that allow the consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth.” To get through the day, she wrote, people eventually embrace “the absolute refusal to believe the truth of anything.” I had first jotted that line down a few years earlier, to make sense of my life in China. I had not expected it would be relevant once I came home.

***

Source:

- Evan Osnos, Wildland: The Making of America’s Fury, 2021, pp.312-313

A Peculiar Kind of Cynicism

It has frequently been noticed that the surest long-term result of brainwashing is a peculiar kind of cynicism—an absolute refusal to believe in the truth of anything, no matter how well this truth may be established. In other words, the result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lies will now be accepted as truth, and the truth be defamed as lies, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth v.s. falsehood is among the mental means to this end—is being destroyed.

— Hannah Arendt, ‘Truth and Politics’

The New Yorker, 25 February 1967