Watching China Watching (XIX)

In Saying the Unsayable we noted that China first essayed the global reach of its United Front strategy during the international leg of the 2008 Olympic Torch Relay. It was also the year that the People’s Republic formulated a new propaganda push to tell The China Story 中國的故事, something that has been taken up vigorously under Xi Jinping since 2012. The United Front work of the Chinese party-state combined with its uneven attempts to promote Chinese Soft Power have focussed in on what some now call Chinese ‘Sharp Power’. Given the directed, acupuncture-like strategy of Chinese efforts — not to mention public haranguing and private cajoling — however, I prefer to describe it as ‘Pointed Power’.

[Note: See also A Decade of Telling Chinese Stories, 1 May 2022.]

In The Battle Behind the Front (China Heritage, 25 September 2017), a precursor to the Watching China Watching we noted that,

Born in revolution and nurtured by war, the United Front Department is a semi-covert arm of Party policy. Students of high Cold War subversion will note that China’s United Front today has a parallel in the peaceful evolution strategy formulated by US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in the 1950s.

Through canny political alliances, tireless ingratiation with business groups and social elites, as well as by means of its cloying cooptation of cultural figures and student activists, the cadres working the United Frontier remain constantly vigilant, and forever combat ready. The mission of the United Front is to disarm the enemy, confound the naïve and secure long-term support for the Party’s policies and strategic aims. After all, 統戰 United Front is short for 統一戰線 ‘United Battle Front’.

We would also argue that the People’s Republic of China has been on an ideological war footing with Western market democracies since the bloodshed of 4 June 1989. Some aver that this ideological contestation — which is reflected in a slew of domains including trade, technology, armaments, territorial expansion, and so on — although not quite constituent of a new Cold War 冷戰, and still some way from becoming a Hot War 熱戰, is nonetheless a Cool or Chilly War 涼戰.

The contours delineating the motivations, battle lines and strategies of the Sino-West Chilly War are studied by a range of China Watchers, some of whom, apart from tracking official party-state discourse, also have their ears to the ground ever ready to detect the subterranean rumblings of Chinese thought and possibility. Others with a bent for influencing policy, at the same time as turning a profit, offer futurist prognosticatications.

***

The tradition of reading and translating among China Watchers dates from the first encounters between Westerners and the Chinese empire. We will end Watching China Watching with an account of that early history titled ‘Empires of Paper’. But here, in this penultimate installment of the series, we contemplate the future.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 February 2018

China Watching & China Warning

The Editor, China Heritage

Watching China Watching with Simon Leys’ observations on The China Expert and László Ladány’s Ten Commandments. Both writers were painstaking in the reading and masterful interpretation of a China that, for them, ‘lay in plain sight’. That is, they took seriously what the official media of the People’s Republic of China said about China, or at least its version of China, as well as speaking with people from the Mainland and delving into their accounts of real life in Maoist China. Although at the time China scholars and watchers of China in governments and intelligence agencies around the world used Ladany’s China News Analysis as a major source on the PRC, Simon Leys was attacked, in particular in France, and his views, as well as his sources of information were questioned and frequently derided.

Simon Leys famously introduced in a comprehensible fashion the unedited words of Mao Zedong from Red Guard publications, along with the rancorous debates among Red Guards, opening up a word of division and dissent that had been silenced since the outpourings of the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1956. (The political scientist Stuart Schram provided an important, if more academic, service in his books Mao Tse-tung Unrehearsed in 1974 and Chairman Mao Talks to the People: Talks and Letters: 1956–1971 in 1975) Leys also introduced readers to the Li Yizhe Big-character Poster 李一哲大字報 (the formal title of which was: 關於社會主義的民主與法制——獻給毛主席和四屆人大). The 26,000-character poster was the product of a collaboration between four non-Party Marxist writers, and it was posted on the streets of Canton/Guangzhou in October 1974 in the hope that it would contribute to discussions at the upcoming National People’s Congress, the first scheduled for many years (see On Socialist Democracy and the Chinese Legal System: The Li Yizhe Debates, 1985). For the student of Xi Jinping’s China this poster is worth reading. I have previously noted thad aspects of Xi’s ideological wowserism recall Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement and Liu Shaoqi’s dull moralising legalism, but the Li Yizhe group’s characterisation of the Lin Biao era of the Cultural Revolution (c.1968-1972) as ‘feudal fascism’ 封建法西斯 is also eerily salient today.

The ‘Canton Poster’, as the Li Yizhe work was also known, was in some regards a precursor to the Democracy Wall of Beijing, a public forum of protest from 1978 until it was closed down by the authorities in late 1979. Beijing Street Voices: Poetry and Politics of China’s Democracy Movement (1981) offered English-language readers a selection of posters and essays from the Wall and, over the years, it was followed by works that introduced the ideas, experiments and aspirations of a range of Chinese thinking people, from artists and intellectuals to dissidents. My own work with John Minford (from Trees on the Mountain in 1983 and Seeds of Fire in 1986-1988 to New Ghosts, Old Dreams in 1992, with Linda Jaivin) contributed to exploring contemporary China through the voices of people wanting to be heard outside the confines of officialdom.

Since then, many important works and projects have appeared giving international readers access to Chinese ideas, debates and prognostications. In this, the penultimate installment in our series, we introduce a few recent examples of this ongoing tradition.

Fraught Futurology

Political scientist David Shambaugh says that China’s Future (2016) is based on ‘four decades of China-watching and on visiting or living in the country every year since 1979, and it offers my best estimations about China’s future evolution over the next decade or two.’ Instead of a monocular view of the future of the People’s Republic, he provides ‘a menu of alternative pathways that China could follow’. It’s a banquet that, perhaps in concert with the avowed austerity of the Xi Jinping era, consist of four dishes, or ‘four essential choices’ for the Chinese: Neo-Totalitarianism, Hard Authoritarianism, Soft Authoritarianism and Semi-Democracy.

In recent years, Shambaugh, a respected China Watcher with decades of observation and a considerable body of work behind him, has veered towards a form of collapsism (see his The Coming Chinese Crackup, Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2015, and my observations in Peter Hartcher, Is the Chinese dragon losing its puff?, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March 2015). This variety of China analysis has been in vogue for as long as the People’s Republic itself. In his 2016 book, Shambaugh declares that ‘if the regime stays on its current course, I predict that economic development will stagnate and even stall, exacerbating already acute social problems, and producing the protracted political decline of the ruling Chinese Communist Party’ (China’s Future, p.16).

Despite all of this, and caveats about the long history of failed China predictions, Shambaugh does offer serviceable, if somewhat platitudinous, advice on the do’s and don’ts of China Watching:

China is certainly distinct, but it is not unique; it is experiencing many of the same challenges that other newly industrializing economies and societies, as well as Leninist polities, pass through. Being cognizant of China’s own history is also important, as distinguishable patterns within dynastic cycles are also relevant. It is also important to have an awareness of the megatrends associated with globalization that affect all societies in the world today: technological changes, the revolution in communications, international politics, ecological systems, ideational trends, social movements. China is not immune, after all, to the exogenous global forces sweeping our planet and shaping the future of humankind. We should not get caught up in the fashionable analytical zeitgeist of the day within China-watching circles. Scholars must also be vigilant against self-censorship or intimidation from the Chinese government, or the blind acceptance of fashionable propaganda narratives (提法) and slogans (口号) used by the Chinese authorities to describe their policies. Maintaining one’s independent judgment is crucial.

Finally, and perhaps most important, we should not anticipate that developments in China will be linear — straight-line projections of the present (“path dependency”) or “muddling through.” Sharp changes of course have occurred with some regularity throughout Chinese history, and the country has a proven capacity to surprise the world. One should always expect the unexpected in China.

— China’s Future, p.13

Thinking People’s China

In past work, Shambaugh, who is also an acknowledged international relations expert, has also analysed the landscape of Chinese IR thinking (see his China’s International Relations Think Tanks, The China Quarterly, no.171, September 2002: 575-596 and China Goes Global, Oxford University Press, 2013). Various other attempts have been made to map the shifting terrain of China’s non-party ideological cum-intellectual world in recent decades. A prerequisite to appreciating the way these Chinese writers think, and write, about the intellectual landscape of their world, is a familiarity with the habits of Maoist taxonomy and periodisation. This can be achieved in a modest fashion by reading a few basic works by Mao, in particular his March 1927 Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan 湖南農民運動考察報告, as well as a few key later works that offer a narrative of the Chinese revolution, classes and contradictions (see, for example, On New Democracy [1940] and On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship [1948], which we touched on in White Paper, Red Menace in this series). The matrix of Maoism remains germane to Chinese discourse related to such disparate subjects as history, ideology, narrative, social groups and so on. It offers a framework and an approach that is reinforced by academic social science practice. Seemingly dated and irrelevant Maoist texts still underpin the official Chinese worldview, and they inform the manner in which the party-state speaks about itself, to itself as well as presents itself to both China and the world.

We should not forget that non-party Chinese thinkers have also been dissecting intellectual and political trends since the 1960s. In the mid 1960s there were Yu Luoke’s insights into Class Status (for which eventually paid with his life), and the Li Yizhe Big-character Poster that analysed Maoist ‘feudal fascism’ in the 1970s, mentioned above. Throughout the 1980s thinkers like Jin Guantao 金觀濤, Gan Yang 甘陽 and Xiao Gongqin 蕭功秦, to name but a few, studied and publishing assiduously on the schema of Chinese intellectual and political debate.

From the late 1980s, the Shanghai-based intellectual historian Xu Jilin 許紀霖 has been an outstanding and dispassionate observer of the resonances of Chinese history, thought and politics in the modern era. As a scholar alert to the New Authoritarian ideas of Wu Jiaxiang 吳稼祥 and Wang Huning 王滬寧, he later outlined the features of a new kind of Chinese state fascism (economism + nationalism). It has formed a body of thought that inherits in particular the legacy of Stalin, and in alerting his readers to it he foresaw the rise of Xi Jinping-ism.

It has been over two decades since these analyses moved online, see for example Gloria Davies and my ‘Have We Been Noticed Yet?’ (Geremie R. Barmé and Gloria Davies, ‘Have We Been Noticed Yet? – Intellectual Contestation and the Chinese Web’, in Edward Gu and Merle Goldman, eds, Chinese Intellectuals Between State and Market, London/NY: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004, pp.75-108). Mark Leonard, co-founder of European Council on Foreign Relations, realised early on the value of introducing Chinese thinkers to Western readers through interviews and translations, and he did so in What Does China Think? (2008) and China 3.0 (2012). A clutch of officially coddled independent Marxists like Wang Hui 汪暉 and Cui Zhiyuan 崔之元 are masterful in navigating the treacherous waters between the Mainland and international academe, and their fellow travellers now enjoy key academic posts.

Key Thinkers in The China Story project (2012-2015) launched a piecemeal account of China’s contemporary intellectual world, while The China Dream Project led by a group of senior academics including Timothy Cheek, Gloria Davies, David Ownby and Joshua Fogel, and in collaboration with Xu Jilin, promises a comprehensive body of work in English.

In China’s Futures: PRC Elites Debate Economics, Politics and Foreign Policy (2015) Daniel Lynch undertakes his own analysis of Chinese opinion, as does the more recent MERICS analysis of online schools of thought titled Ideas and Ideologies Competing for China’s Political Future: How online pluralism challenges offcial orthodoxy. The authors of this latter work, published in October 2017, say:

In this study, we identify eleven ideological clusters and label them according to their most characteristic properties. These groupings display varying degrees of conformity with or opposition to the official party-state ideology, for example:

- ‘Party Warriors’ are most closely aligned with the CCP, and regularly support official views in social media discussions.

- ‘China Advocates’, ‘Traditionalists’, ‘Industrialists’, and ‘Flag Wavers’ represent different strains of nationalism. They support the ‘China Path’, but not necessarily the policies of the CCP. ‘Market Lovers’ fight with ‘Mao Lovers’ and ‘Equality Advocates’ over the best economic model for China. ‘Market Lovers’ are increasingly in opposition to the party-state as the party moves towards tighter control of the market.

- ‘Democratizers’, ‘Humanists’ and ‘US Lovers’ are the furthest removed from the party state ideologically. They defend freedom of expression and universal values as prerequisites for human dignity and democratic rule.

This very useful contemporary digest is at times marred by a certain glibness of tone and the fact that the authors seem to suggest that the Xi Jinping era (2012-) represents a not-insignificant departure from the party-state’s behaviour during earlier phases of the post-Mao reform era (c.1978-2008). Indeed, in the executive summary of Ideas and Ideologies Competing for China’s Political Future it is claimed that:

The party center under Xi Jinping aims at creating a distinct Chinese ideological framework, the ‘China Path,’ as an alternative to ‘Western’ concepts. The party seems to view it as essential for its own survival to fill the perceived moral vacuum in a society which has been more inspired by consumption than by socialist campaigns ever since the reform and opening policy paved the way for China’s economic rise. The CCP also tries to use the current crises in Western liberal democracies to discredit ‘Western’ concepts of political and economic order.

The building blocks of this unifying ideology can be summarized as follows:

- Only a one-party system can effectively turn China into a prosperous, highly developed nation. Old slogans leading back to the communist founding fathers or Confucian thought are redefined for new purposes.

- The fight against corruption, for instance, is sometimes framed as the new manifestation of class struggle.

- Leninist principles are upheld as a constituting element of political life in China.

- Ideology needs to constantly adapt to changes in the world, technological advancement is defined as an integral part of China’s future development.

- The CCP’s ideology selectively draws on foreign ideas, institutions and concepts, for example by combining centralized economic planning and elements of market economy.

- Terms like ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ are borrowed from ‘Western’ value systems and then redefined. Democracy for instance is not equated with a multi-party system with free elections but used to describe a ‘consultative’ process of decision making.

Excellent though this may be, and at the risk of sounding even more churlish than usual, one must point out that all too often China Watching reports, analyses and books indulge in this kind of ‘presentism’. That is, despite protestations about the value of previous scholarship, an emphasis on the importance of understanding history, the need for ‘China literacy’ and the rest of the modish China Studies catechism of today, authors often strain to make a selling-point of their unique aperçu, or would claim some unprecedented insight or new angle. Such efforts can perilously endanger the need for those who would watch also to remember, recall and remind. (Of course, history can also be a good marketing tool, and this is particularly the case in the discussions surrounding the Thucydides Trap, and the mechanistic application of an ancient Greek text to the future of the US-China relationship.)

The Xi Jinping post-2012 party-state narrative builds on The China Story as articulated in 2008, which itself was an extension of a series of historical adjustments from the Jiang Zemin era (which were constructed on the basis of Mao Zedong’s ‘On New Democracy’, as well as the history texts, compendia and readers of the 1950s and early 1960s). As for the evisceration of Western concepts for Chinese use, such an approach has underpinned state ideology since the late-imperial era (for instance, one only has to recall the dyadic Essence / Form 體用 relationship).

As was the case with debates about the Self-Strengthening Movement of the 1860s, the Hundred Days of 1898, the New Politics of the 1900s, then at various points during the Republic, in particular during the Civil War period of the late 1940s when the Communist Party creatively adapted liberal discourse to its own purposes, and a number of times since the death of Mao Zedong and following 1989, differences are emphasised at the expense nettlesome continuities. This is an approach common in the traditions of China Watching that have been the subject of our Watching China Watching series.

As we have attempted to indicate: watching and listening to the here-and-now requires attentiveness to the there-and-then, the history of socio-political change in China since at least the 1860s Tongzhi Restoration 同治中興. Like many the academic China Watchers, however, we are alert to the need to engage with broader perspectives allowed by modern scholarship, social science methodologies and new theoretical models.

All of these are important for those who not only watch China now, but try to think about it in the context of elite Chinese opinion and how such opinions conceive of, enable and may effect the future. As an historian, my main interest in this first series of Watching China Watching is to provide material related to the past. The future must needs be a topic for another time: the planned China Heritage Annual 2018: Watching China Watching.

Related Material:

- Daniel Lynch, China’s Futures: PRC Elites Debate Economics, Politics and Foreign Policy, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015

- China’s Future, Polity Books, 2016

- Linda Jakobson and Bates Gill, China Matters: Getting it Right for Australia, Melbourne: Black Books Inc., 2017

- Bill Bishop on what it takes to be a good China-watcher, Sinica, 4 May 2017

- Kristin Shi-Kupfer, Mareike Ohlberg, Bertram Lang and Simon Lang, Ideas and Ideologies Competing for China’s Political Future: How online pluralism challenges offcial orthodoxy, MERICS Papers on China, No.5, October 2017

- Takeaways from China’s 19th Party Congress, with Bill Bishop and Jude Blanchette, Sinica, 2 November 2017

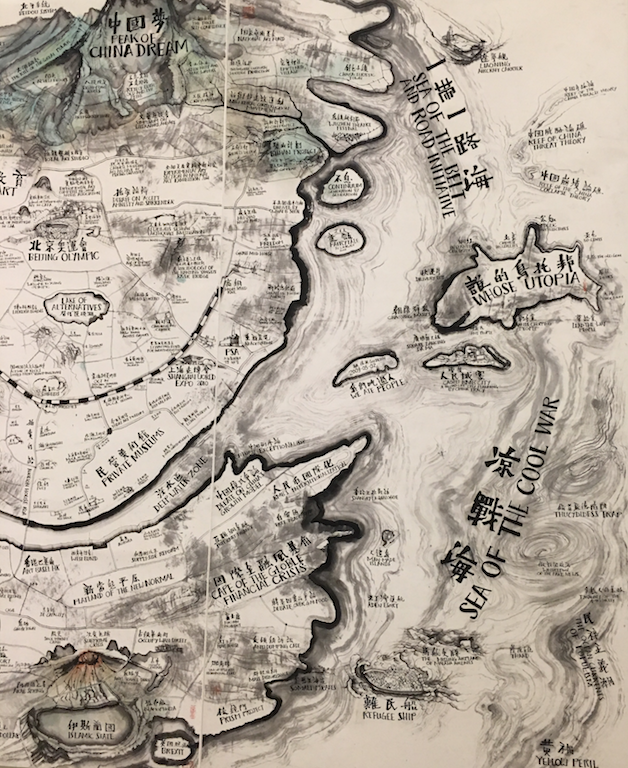

- Ian Johnson: ‘The Biggest Taboo’: An Interview with Qiu Zhijie, The New York Review of Books, 6 January 2018

- Kishore Mahbubani on China’s rise and America’s myopia, Sinica, 8 February 2018

No Hiding and Even Less Biding

It is widely acknowledged that, from the Hu Jintao era (2003-2012), China gradually moved away from a successful and long-term approach to international affairs known by the shorthand ‘Hide and Bide’ — hiding true intentions and biding time, or 韜光養晦 in Chinese. The policy had been formulated by Deng Xiaoping following the events of 1989, and in light of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the predominance of the United States in a unipolar world. Deng summed up the approach in four aphoristic expressions: 冷靜觀察、沈著應付、韜光養晦、決不當頭、有所作為, or ‘observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership’. In recent years, assertion has replaced avoidance and the Communist party-state has made public its own hegemonic impulses, much to the consternation of other Asia-Pacific nations and their traditional allies.

In relation to Australia, as the noted strategic thinker Hugh White put it when discussing the influence of China with Linda Jaivin:

Lucky countries don’t really need a foreign policy, because the world works well for them. They just have to decide what they think about others’ problems. … But it becomes serious when the world stops working so well for you. Then you need a real foreign policy, because you need to influence your international environment in order to promote your security and prosperity.

— Linda Jaivin, The New Era: ready or not China is here

The Monthly, December 2017-January 2018

White uses his latest provocation, Without America: Australia in the New Asia, to stir further the debate about China in Asia and the Pacific. He baldly states that:

The contest between America and China is classic power politics of the harshest kind. We have not seen this kind of struggle in Asia since the end of the Vietnam War, or globally since the end of the Cold War. The generations of politicians, public servants, journalists, analysts and citizens who grew up with power politics and knew how it worked have left the public stage. Political leaders like Menzies and Fraser, Curtin and Whitlam, and Hawke, Keating and Howard; public servants like Arthur Tange; journalists like Peter Hastings and Dennis Warner; academics like Hedley Bull, Tom Millar and Coral Bell; and the voters who lived through the wars and struggles of the first three-quarters of the twentieth century: they would all find Asia today much easier to understand than we do. We have a lot to learn and not much time to learn it.

And of course it has been harder to acknowledge what has been happening in Asia because it has been so difficult to imagine where it is taking us. We are heading for an Asia we have never known before, one without an English-speaking great and powerful friend to dominate the region, keep us secure and protect our interests. The fear that this might happen — the ‘fear of abandonment,’ as Allan Gyngell calls it – has been the mainspring of Australian foreign policy since World War II, and indeed long before. But since the Cold War ended — a generation ago now — we have forgotten those old fears and begun to take American power and protection for granted. We have come to depend more and more on America as its position in Asia has become weaker and weaker.

We have been happy to get rich off China’s growth, confident that America can shield us from China’s power. Now it is clear that confidence has been misplaced; we need to start thinking for ourselves about how to make our way and hold our corner in an Asia dominated by China.

That is what this essay is about. It looks first at how America is losing the contest with China, and then at Australia: how we have responded to the US-China contest so far, why we have got it so wrong, and what we can do now to manage the new reality we face.

—Hugh White, The Quarterly Essay, December 2017

***

The impact of China’s increased presence, and global reach, was the theme of The Battle Behind the Front, previously published in China Heritage. Concerns about China’s soft power strategies have found articulation in the work, and policy recommendations of scholars like Anne-Marie Brady in New Zealand, the independent writer Jichang Lulu, journalists and academics in Australia, concerned commentators in North America and Eastern Europe, as well as by Clive Hamilton in his pointedly titled Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia (March 2018). The Australian government has responded to concerns raised since 2016 with proposed new legislation (some argue that the draft laws are excessive, reflecting nothing less than a pro-American ‘anti-Chinese jihad’), while in Europe, a major study by China specialists has dissected PRC influence while offering a range of suggested (and urgent) policy initiatives. Globally a debate about a China-related Cold War is looming.

Those who offer policy advice and practical responses to the escalation of egregious PRC behaviour, as well as those of more moderate views, all invariably tout ‘China literacy’, the greater need for a better understanding of China in holistic terms and so on and so forth. New Sinology has been propounded as just such an approach since 2005, and the Australian Centre on China in the World which I established with the support of then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, and ANU Vice-Chancellor Ian Chubb in early 2010 — a centre that drew on the advice and expertise of many established as well as up-and-coming scholars of China — was created specifically to further these very ideas in practice. From 2012, the Centre developed The China Story Project to give practical form to this kind of intellectual and academic induction. It continues, although in markedly reduced form, to do so today.

Ideas about ‘China Literacy’ are hardly new. The writers featured in Watching China Watching — and here I think in particular of Richard Baum, Simon Leys and László Ladány — have made the case for informed engagement and independent critique for nigh on fifty years. Today, as this tiresome litany is repeated, because the pressing military, political, social, educational and mercantile ramifications of China Illiteracy loom larger than ever, perhaps this time around responses will be more than mere lip service.

Related Material:

- The Australia-China Story Archive, 2007-2015

- Geremie R. Barmé, Australian and China in the World: Whose Literacy?, 5 July 2011

- Christopher K. Johnson, President Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road” Initiative: A Practical Assessment of the Chinese Communist Party’s Roadmap for China’s Global Resurgence, Washington: Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2016

- The Freeman Chair in China Studies, Washington: CSIS, ongoing

- China Leadership Monitor, The Hoover Institution, ongoing

- Stephen FitzGerald, Managing Ourselves in a Chinese World: Australian Foreign Policy in an Age of Disruption, Gough Whitlam Oration, 17 March 2017

- The Battle Behind the Front, China Heritage, 25 September 2017

- Kevin Rudd, China’s Rise and a New World Order, La Trobe University, 26 October 2017

- Elizabeth C. Economy, Beware Chinese Influence but Be Wary of a China Witch Hunt, Asia Unbound, 22 December 2017

- Hugh White, Without America: Australia in the New Asia, Quarterly Essay, December 2017; and a YouTube précis

- Linda Jaivin, The New Era: ready or not China is here, The Monthly, December 2017-January 2018

- Eric Fish, Caught In A Crossfire: Chinese Students Abroad And The Battle For Their Hearts, SupChina, 18 January 2018

- Michael Swaine, Chinese Views of Foreign Policy in the 19th Party Congress, China Leadership Monitor, Issue 55 (Winter 2018)

- Clive Hamilton and Alex Joske, submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security related to the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Bill 2017, National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill 2017, Hansard (Uncorrected Proof), 31 January 2018. For Clive Hamilton’s private statement to the committee, see pp.51-60

- Nick McKenzie & Richard Baker, Controversial China book may get parliamentary protection, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 2018

- Peter Drysdale and John Denton, Australia must move beyond Cold War thinking, East Asia Forum, 5 February 2018

- Thorsten Benner, Jan Gaspers, Mareike Ohlberg, Lucrezia Poggetti and Kristin Shi-Kupfer, Authoritarian advance: Responding to China’s growing political influence in Europe, Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) and Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi), 5 February 2018

- Alex Joske, Beijing Is Silencing Chinese-Australians, The New York Times, 6 February 2018

- Martin Hála, On CEFC and CCP Influence in Eastern Europe, China Digital Times, 8 February 2018

- Paul Karp, Kevin Rudd accuses Turnbull government of ‘anti-Chinese jihad’, The Guardian, 11 February 2018

- Nick McKenzie, Publish and be free: a note to our politicians, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 February 2018

- Clive Hamilton, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia, Richmond, Vic: Hardie Grant Books, March 2018

- David Brophy reviews Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia by Clive Hamilton, Australian Book Review, No.399 (March 2018)