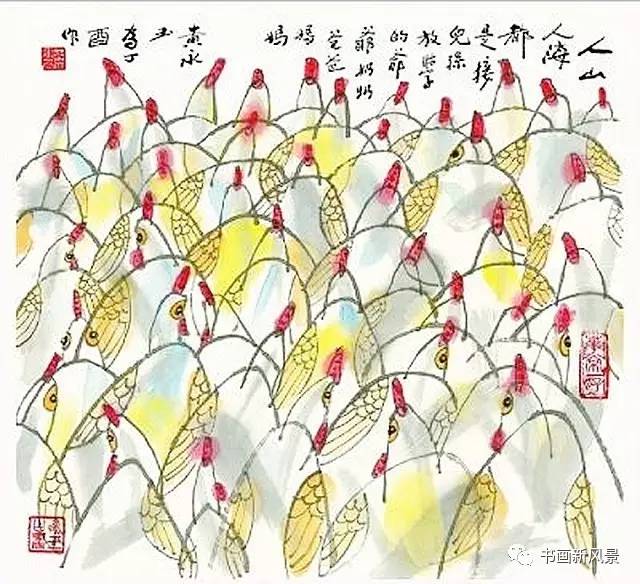

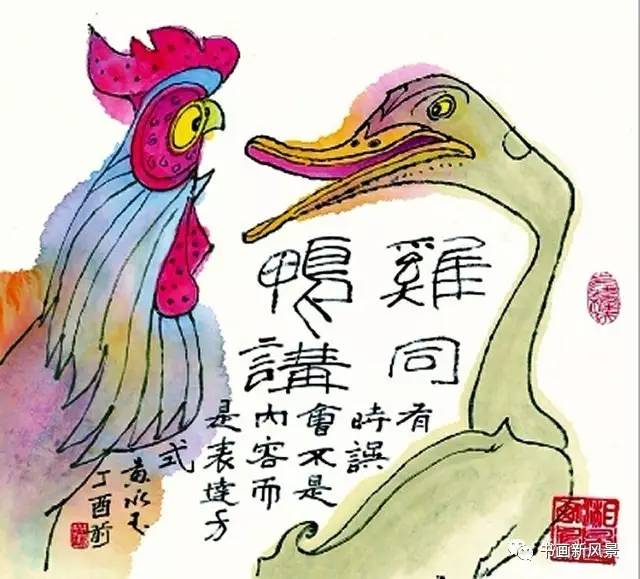

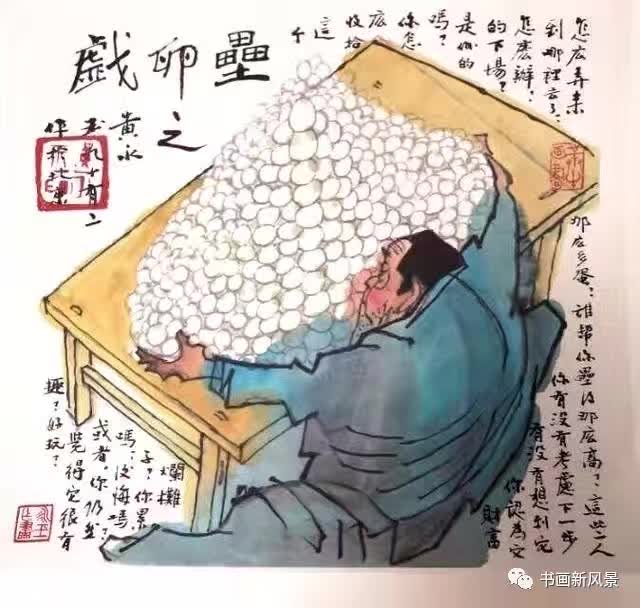

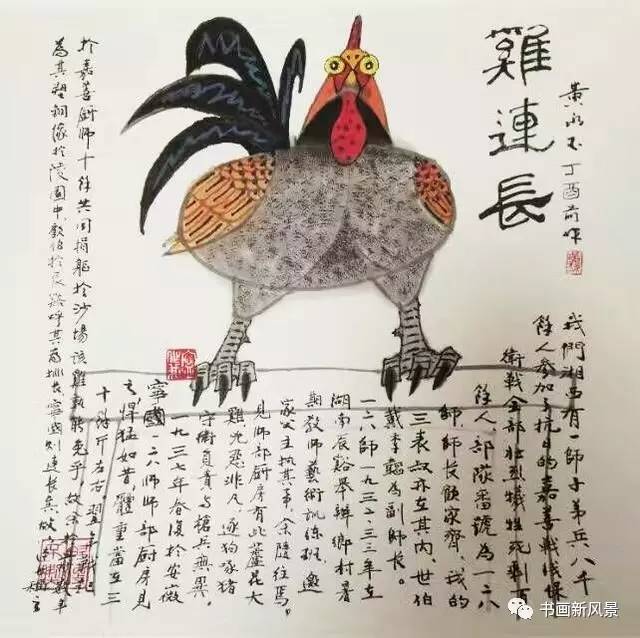

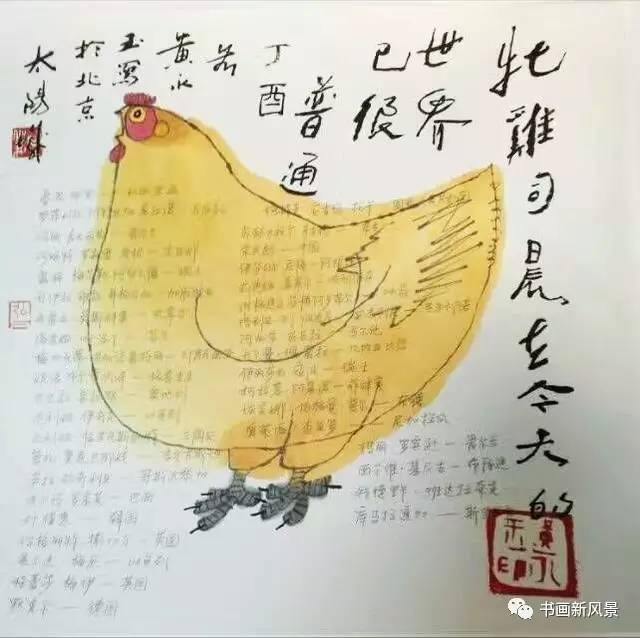

The word ji 雞 is a homophone for ji 吉, ‘auspicious’, a term used in such expressions as jixiang 吉祥 and jili 吉利 or good fortune, and common in the new year salutation: 大雞(吉)大利. Artists and artisans alike have used everything from the humble chick, to the hen as well as the statuesque rooster in their work since ancient times. The annual desk calendar produced by the Palace Museum in Beijing, 故宮日曆, which draws on a formidable collection, offers ji 雞 every day of the year 2017. (These museum calendars were originally produced from 1933 to 1937; the practice was only revived under the People’s Republic in 2010.)

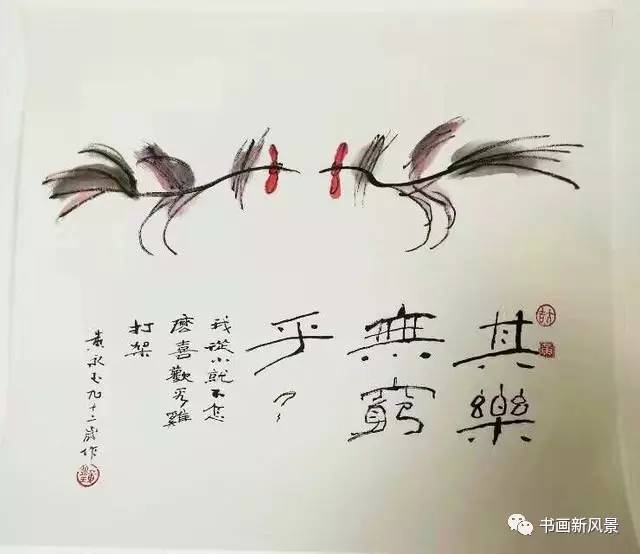

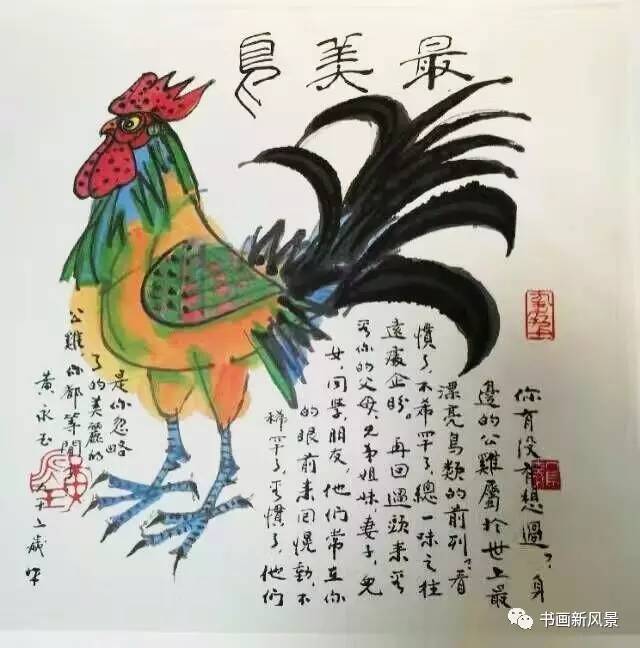

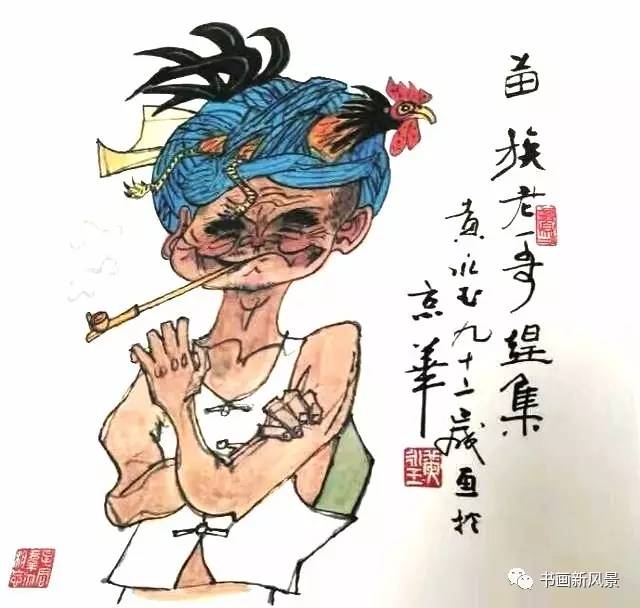

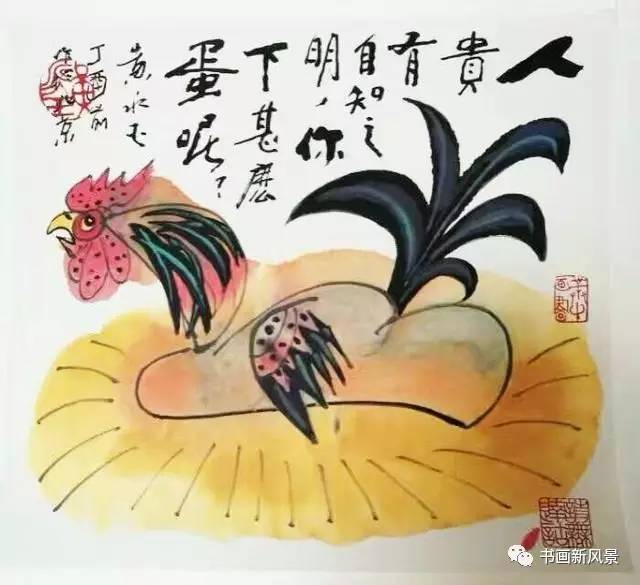

In the lead up to Chinese New Year on the 28th January 2017, the Beijing-based artist, writer, humorist and raconteur Huang Yongyu 黄永玉, made twelve paintings featuring ji 雞. From 2006, Huang painted an annual calendar of twelve works on the theme of each of China’s traditional Zodiac Animals. He had done so partly out of pique since, although his work had been used in official postage stamps over the years (starting in 1980), in 2006 his Bingxu Year of the Dog 丙戌狗年 picture of a micturating canine 狗撒尿 had been turned down. He completed the cycle of twelve animals this year, 2017.

As Huang writes in an introductory note to the Twelve Ji that appear below, looking back over the past twelve years (to when he was a mere eighty-year old):

Time has truly flown by and, in the twinkling of an eye, I have painted all Twelve Zodiac Animals. I can’t avoid the fact that I’m an old man, and there’s not much puff left in me. 时间是那么地飞快流逝,眼看我画完了足足十二年的生肖月历。人,究竟还是老了,九十二岁的人再挺也挺不到哪里去了。

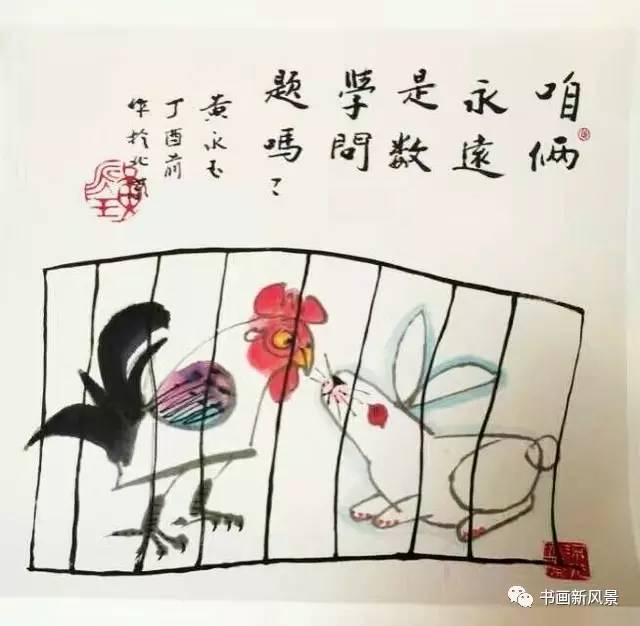

The ancients claimed that the ji 雞 has Five Virtues: with its crown it appears civilised; with the spurs on its feet it is martial; faced with an enemy it courageously attacks; in the presence of food it displays its humanity by clucking for others to join in; while in the early hours it never fails its duty. It’s intriguing that people share the same qualities. 古人說,雞有五個特點:頭戴冠者文也,足搏距者武也,敵在前敢闖者勇也,見食相呼者仁也,守夜不失時信也,我看人若是也有這五番講究,應該是相當有意思的。

Here, as in so much of his other work over the decades, Yongyu gives both voice and form to a particular sensibility or quwei 趣味, one that reflects the complex temper of the cultural universe I frequently refer to in my work on New Sinology. Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) first introduced me to that world as an undergraduate student of Chinese and then, in China, friends like Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang, Wu Zuguang, Huang Miaozi, and many others initiated me into the parallel realm of latter-day literati that miraculously (but only just) survived Mao. It is a land of the heart-mind that is part of a lineage leading back to the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove and earlier. That group, and the thinkers and writers who inspired the Sages, as well as a disposition in which culture in its most vibrant and inclusive sense, light the way for The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology.

Previously, Huang Yongyu’s Zodiac Animals featured in my essay on the Bingshen Year of the Golden Monkey 丙申猴年, published in The China Story Journal during the dying days of my editorship in early 2016. Some years prior, Yongyu’s work appeared in that Journal to celebrate the start of the 2013 Guisi Year of the Snake 癸巳蛇年.

Some thirty years prior to all of this, Yongyu encouraged me to translate his Animal Crackers 罐齋雜記, and some of that work features in the multimedia section of the website created for the 2003 film Morning Sun, which I made with Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon, who are also long-time friends of the artist.

These Year of the Rooster pictures first appeared in the pages of Beijing Evening News 北京晚报; subsequently, they were widely reproduced online. An exhibition of the ‘Twelve for Twelve Months’ 十二个十二个月——黄永玉生肖画展 featuring the paintings Huang Yongyu has created for the twelve Zodiac Signs over twelve years opens at the National Musuem of China in Beijing today (19 January). The show will continue until 12 February 2017.

These Year of the Rooster pictures first appeared in the pages of Beijing Evening News 北京晚报; subsequently, they were widely reproduced online. An exhibition of the ‘Twelve for Twelve Months’ 十二个十二个月——黄永玉生肖画展 featuring the paintings Huang Yongyu has created for the twelve Zodiac Signs over twelve years opens at the National Musuem of China in Beijing today (19 January). The show will continue until 12 February 2017.

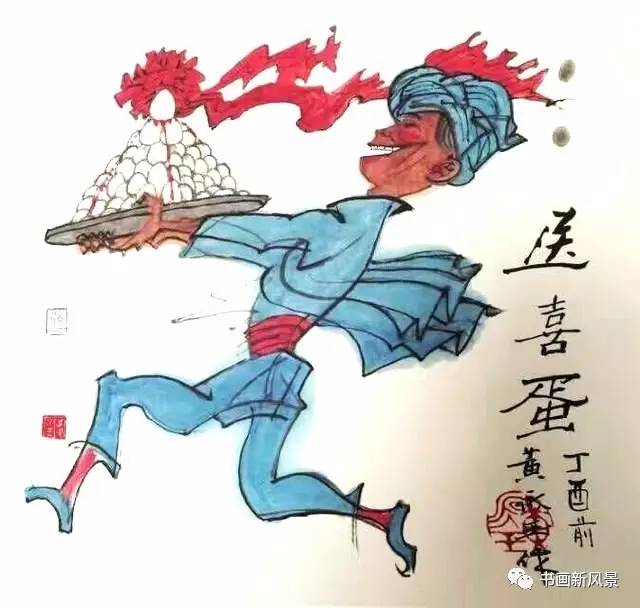

The translated legends and written explanations are mine. See also The Year of the Rooster, On Reading and The Year of the Rooster, On Eating, Imbibing, Injecting & Speaking.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage