Dog Days (III)

戊戌男兒

In the series Watching China Watching in China Heritage we noted how modern leaders — from Sun Yat-sen, through Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Ching-wei 汪精衛 to Mao Zedong — availed themselves of the imagery of the country’s dynastic past. Mao in particular continues to be fashioned as a ‘new emperor’ and, as we noted in For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone — Watching China Watching (XII), both he and his coterie of thinkers and propagandists knowingly manipulated the tropes of the imperial past with considerable dexterity. As I wrote there:

Shortly after assuming power, Xi Jinping too availed himself of an imperial allusion. During his first Tour of the South in December 2012, the just-appointed Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party is said to have referred to the reasons behind the collapse of the Soviet Union. In doing so he supposedly quoted a famous line of poetry from the dynastic past: ‘No real man among their number’ 更無一個是男兒. It comes from a verse attributed to Madam Flower Bud 花蕊, a concubine of Meng Chang 後主孟昶, ruler of the kingdom of Later Shu 後蜀. The poem reads in full:

Flags of surrender on the ramparts

Deep in the palace how can I know:

140,000 lay down their arms,

No real man among their number.

君王城上竪降旗,

妾在深宮哪得知;

十四萬人齊解甲,

更無一個是男兒.

In effect, Xi was saying that now China had just such a ‘real man’ 男兒: himself. It did not bode well for the country. Official China may have stifled the country’s #MeToo moment, but with the announcement in late February 2018 that the Constitution would be revised to allow the state leader to serve more than the previously allotted two terms, China’s Chairman of Everything was in fact claiming there is #OnlyMe.

***

In 1928, during a wave of revolutionary fervor following the success of the Northern Expedition and the unification of China under the rule of another one-party state — the Nationalist Party government in Nanjing — in the hope of preventing backsliding and to frustrate the ever-present dynastic aspirations of the ambitious, some thinkers like Jing Hengyi (經亨頤, 1877-1939) proposed selling off the imperial patrimony housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing (at the time the city had been renamed ‘Beiping’) and dismantling the Forbidden City itself.

As a member of the Republican government Jing formally canvassed a bill titled ‘Abolish the Palace Museum and Sell or Auction Off All of the Objects in the Former Palace in Lots’ 廢除故宮博物院,分別拍賣或移置故宮 一切物品 on 28 June 1928. Among other things, he suggested that the imperial thrones 寶座 should be banned from public sight so as to discourage people from lusting after imperial power. Furthermore, he said, the name ‘Former Palace’ 故宮 should be changed to ‘Discarded Palace’ 廢宮 as the word ‘former’ 故 had various positive connotations and could easily be taken to denote a measure of nostalgia for the past.

The proposal was hotly debated and a committee was set up to deal with the ‘illicit property’ 逆產 of the former imperial house. By the end of the year, however, extremism was on the wane; the committee was disbanded and the proposal dropped.

Selling off or destroying the relics of the dynastic past appealed to the iconoclastic spirit of Chinese revolutionaries from the 1920s until the 1970s. Meanwhile, the authoritarian impulse was enthroned by successive governments. Once, in 1941, Deng Xiaoping even warned against that the practice of ‘one party ruling the nation’ 以黨治國 under the Nationalist Party could also corrupt the Communists. (He wrote: 我們反對國民黨以黨治國的一黨專政,尤要反對國民黨的遺毒傳佈到我們黨內來。)

— adapted from Geremie R. Barmé, The Forbidden City,

London: Profile Books, 2008, p.133; and, Chapter 6, online notes

***

The miscegenation resulting from a century during which dynastic thinking, Marxist-Leninist historicism and the vanity of the authoritarian personality is an extraordinary creature. Although, as many commentators have noted, China shares, and indeed celebrates, the ‘authoritarian turn’ of the twenty-first century, it is also a country with long-unresolved issues to do with political participation and succession. These are topics previously touched on in essays by the Hong Kong political commentator Lee Yee and published in China Heritage.

Despite the fitful de-Maoification of the late 1970s and early 1980s, as a one-party state China never really bid farewell to the cult of personality. The grand architect of the country’s successful economic — and failed political — reforms, Deng Xiaoping, was deified both during and after his rule. The media adulation showered on him certainly never reached the absurd heights of the Mao cult, but for analysts and commentators to have claimed at the time — or subsequently — that by instituting a form of collective leadership Deng and his fellow gerontocrats effectively rid the country of the cult of the leader is ridiculous. Ever since the rejection of substantive political reform in China, the reappearance of an authoritarian personality at the apex of the party-state hierarchy has been a dark possibility. Given the decade of charismatic deficit under Hu Jintao from 2003 to 2012, both Xi Jinping and Bo Xilai promised lineage, competence and personal domination. The forty-year arc of return is long but its workings would now appear to be inexorable.

In an obvious reference to Xi Jinping’s late-2012 line in poetry, Lee Yee, the celebrated Hong Kong political commentator whose work features in The Best China, titles the following essay 戊戌男兒, literally ‘The Real Man of the Year of the Dog’. I also translate it as ‘Dog Man’. Although China’s Man of the Dog Year is Xi Jinping, Lee Yee focusses his discussion on the educator Zhang Baixi and those who should by all rights nurture and protect the free-thinking students in Hong Kong today.

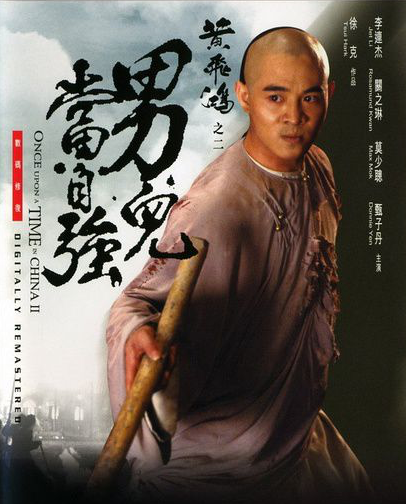

The expression 男兒 will be familiar to fans of the Hong Kong film director Tsui Hark 徐克, whose films about the martial arts patriot and folk hero Wong Fei-hung (黃飛鴻, 1847-1925) are still popular. The theme song of Once Upon a Time in China II 男兒當自強 was written by James Wong 黃霑, an anti-communist comic, writer and lyricist who featured in our 2017 Christmas essay. Titled Be a Man (男兒當自強, or A Man Should Better Himself) the lyrics of the song are:

傲氣面對萬重浪 熱血像那紅日光 膽似鐵打 骨如精鋼

胸襟百千丈 眼光萬里長 我發奮圖強 做好漢

做個好漢子 每天要自強 熱血男兒漢 比太陽更光

(For a version of the song sung in Standard Chinese by

George Lam Chi Cheung 林子祥, see here).

Perhaps this the heart of Xi Jinping’s New Thinking.

***

The Fifteenth Day of the First Month of the New Year 正月十五 marks the first full moon of the Lunar New Year. Generally called Yuanxiao 元宵, literally ‘First Evening’, it is also the height of the Lantern Festival 燈節, traditionally celebrated from the Hanging of Lanterns 上燈 on the Thirteenth Day to the Taking Down of Lanterns 落燈 on the Eighteenth Day of the First Month. The First Evening is also variously called: 上元節、小正月、元夕、小年 or 春燈節.

— from The End of the Beginning 元宵,

China Heritage, 11 February 2017

***

This essay is included in both The Best China and New Sinology Jottings, two China Heritage projects.

Further Reading:

- Yan Jiaqi 嚴家其, Terminal Tenure, trans. David Bandurski, China Media Project, 26 February 2018 (for Yan’s account in full, see 廢除終身制是怎樣產生的?, Open Magazine 開放雜誌, January 2013)

- Jeremy Goldkorn, Don’t Talk About The Constitution In China, SupChina, 27 February 2018

- Li Datong’s Open Letter, trans. David Bandurski, China Media Project, 28 February 2018

- Max Fisher, Xi Set China on a Collision Course with History, The New York Times, 28 February 2018

- Jeremy Goldkorn, Why The Removal Of Presidential Term Limits Shocked So Many In China, SupChina, 28 February 2018

- Javier C. Hernández, China’s Censors Ban Winnie the Pooh and the Letter ‘N’ After Xi’s Power Grab, The New York Times, 28 February 2018

- Lee Yee 李怡, Yuan Shikai on Every Screen 滿屏盡是袁世凱, Apple Daily, 27 February 2018

- Lee Yee 李怡, When It’s Dark Enough, Do the Stars Really Shine Out? 暗透了, 更能看到星光?, Apple Daily, 28 February 2018

- Lee Yee 李怡, Driving in Reverse 開倒車, Apple Daily, 2018年3月2日

The Year of the Dog in China Heritage:

- The Editor, Mondo Cane, The 2018 Year of the Dog 戊戌狗年, China Heritage, 16 February 2018

- Don J. Cohn, A Pride of Pekingese — Dog Days (I), China Heritage, 18 February 2018

- Pu Songling, The Dog Lover — Dog Days (II), China Heritage, 24 February 2018

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

Fifteenth Day of the

First Month of 2018

Wuxu Year of the Dog

戊戌狗年正月十五

2 March 2018

Dog Man

戊戌男兒

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

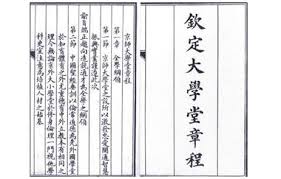

According to the traditional lunar calendar this is a Wuxu Year. The Sexagenary Cycle for counting years has been in use since the Later Han dynasty [second century CE], with a new cycle starting every sixty years. The last Wuxu Year was 1958, a time when, following on from the Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957, the Great Leap Forward was at its height, and that led to the the Great Famine. The Wuxu Year before that was 1898, known variously as the Wuxu Reforms or the Hundred-day Reforms, a period which saw the creation of the Imperial Capital University, China’s first tertiary educational institution. The forerunner both the Peking University and Beijing Normal University the Imperial Capital University was founded to teach Western learning and the arts. 今年是農曆戊戌年。中國在漢代開始推行干支紀年,每60年會重新一個輪迴。上一個戊戌年是1958年,大陸在反右運動後開展導致大饑荒的大躍進;再上一個戊戌年是1898年,那年發生「戊戌變法」、百日維新,創立第一間官辦大學——京師大學堂,目的是教授「西文西藝」,它是北京大學和北京師範大學的前身。

The Wuxu Reforms were undone by the Empress Dowager Cixi and conservative forces at the Manchu court. Six leading proponents of change, including Tan Sitong, were beheaded. With the occupation of Beijing by the military forces of the Eight-nation Alliance sent to relieve the Legation Quarter of the Chinese capital during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, the Imperial University also suffered. In 1902, Zhang Baixi [1847-1907], secretary of the Board of Civil Appointments was made minister in charge of the university. 戊戌變法遭慈禧及守舊勢力反撲致敗,譚嗣同等六君子慘死。1900年,八國聯軍進入北京後,京師大學堂遭受破壞。1902年清政府委吏部尚書張百熙任管學大臣。

Zhang focussed on reviving the university and to that end he did his utmost to attract the talents of the age. In selecting teachers he proposed ‘abandoning the ingrained habits of the past to engage people regardless of their background’, they must be ‘outstanding individuals expert in contemporary affairs’, ‘well practiced men with a grounding in true learning’. He wanted to employ the famous scholar Wu Rulun as the university’s director of studies and he went to pay his respects in full court attire. He knelt before him. Despite the fact that Wu was unmoved by this display, Zhang persisted and pleaded: ‘I beseech you to take on this mission for the sake of the Empire, for the sake of the students of the Empire. If you refuse me, what will become of China?’ Wu, who had prepared an elegant statement refusing the position magnanimously accepted Zhang’s invitation. Later, [the British Malay Chinese man of letters] Gu Hongming was appointed as Wu’s deputy. The university Compilation Bureau [which produced key translated texts for nationwide distribution] was headed by [the thinker] Yan Fu, with [the noted translator] Lin Shu as his deputy. Not long thereafter such leading scholars as Yang Renshan, Tu Jingshan, Wang Yaozhou and Cai Yuanpei were also appointed. The institution became the forerunner of modern Chinese education. 張百熙銳意興學,不遺餘力為學校招攬優秀人才。他提出「應破除積習,不拘成例用人」,選用「才具優長,通達時務」、「明練安詳,學有根底」的人為大學堂教師。為了邀著名學者吳汝綸任大學堂總教習,張百熙穿朝服在不為所動的吳汝綸面前長跪,說:「我為全國求師,當全國生徒拜請也,先生不出,如中國何!」吳汝綸終把多日準備的謝絕詞變為慨然允諾。後又聘辜鴻銘任副總教習,嚴復和林紓分任大學堂譯書局總辦和副總辦。著名學者楊仁山、屠敬山、王瑤舟、蔡元培等,也在不久被張百熙聘用,先後成為中國大學教育的先驅。

During the occupation of Beijing by the Eight-nation Alliance in 1900, Tsarist Russian troops invaded north-east China. In 1902, the Russians concluded a treaty with the Qing government and agreed to withdraw their forces in three stages over a thirteen-month period. The following year, not only did the Tsarist government renege on the treaty, it sent reinforcements and imposed seven new demands on the Qing authorities as a precondition for withdrawing its forces. Students at the Capital University were outraged by the impotent response of the Qing court to this provocation and they launched a Reject Russia Movement the slogan of which was ‘Reject the Russian treaty, protect the whole nation, advance government reform on the way to national revival’. This was the first student movement in modern Chinese history. 1900年八國聯軍期間,沙俄入侵東北。1902年俄國同清政府訂約,規定將侵佔東北俄軍分三期於13個月內全部撤走。1903年,沙俄不僅違約不撤,反而增派軍隊,並向清政府提出了7項無理要求,推行親俄外交的清政府的不作為,激起了青年學生極大憤慨,京師大學堂學生發起了拒俄運動,要求政府「力拒俄約,保全大局,展布新政,以圖自強」。這是中國近代第一次學生運動。

The Reject Russia Movement so unsettled the Qing court that they responded both with contempt and repression. They declared that the students ‘may well claim that they reject Russia, but what they really agitate for is revolution’. The Su Pao newspaper based in Shanghai published a ‘Secret Edict Ordering the Severe Punishment of Students Studying Overseas’ [which revealed that the court was attempting to quell dissent among Chinese students studying in Japan]. The Empress Dowager was particularly incensed by the fact that students of the Capital Imperial University participated in the anti-Russian protests. She was convinced that they were at odds with the Court; their behaviour was the height of disloyalty. She demanded that Zhang Baixi rein them in. 拒俄運動同時也引起清政府的恐慌、敵視和鎮壓,指責學生「名為拒俄,實則革命」。《蘇報》刊出《嚴拿留學生密諭》。慈禧太后對京師大學堂的學生參加拒俄運動甚是惱怒,認為這是和朝廷分庭抗禮,大逆不道。要求張百熙嚴加管束學生。

Zhang’s response was surprising. He wrote a series of formal notes on a petition that he had received from the students. He said: ‘The students are loyal but rightly indignant; their outrage is not that of those bloated with self-regard or due to a misplaced desire to interfere in politics. They are clear-eyed and they understand the gravity of what is at stake. Their outspokenness is not some vacuous complaint. I regard our students as my own and I hold them dear to me. How could I suppress their bold protests or decry them as criminal?’ He added: ‘You students have your independent and incisive views regarding the state of the nation. I encourage you to formulate these in writing and present them to me rather then engaging in rancorous discussion that can so easily fall prey to malign criticism.’ 張百熙的態度卻出人意表。他在學生的信函中批示道:「該生等忠憤迫切,自與虛驕囂張,妄思干預者有別。至於指陳利害,洞若觀火,具征覘(觀察)國之識,迥非無病之呻。本大臣視諸生如子弟;方愛惜之不暇,何忍阻遏生氣,責為罪言!」他還批示:「嗣後諸生研究國聞,確有見地,可隨時著為論說,呈候本大臣批答,籍可考見學識,示以準繩,不必聚論紛綉,授人指滴!」

Zhang ignored Cixi’s call to rebuke the students. Instead, he did what he could to protect students with more extreme views. Later that year, he selected students with the best academic results and sent them to continue their studies overseas. This was the first time a Chinese government formally dispatched university students to study overseas. Some of their number later became scholars and politicians. 張百熙完全不顧慈禧太后「嚴加管束」的旨意。他盡自己的力量保護思想激進學生。這一年年底,張百熙將其中功課優異者送往國外深造,這是中國第一次公派出國留學。這些留學生後來有些成為了政治家和學問家。

How do the grand ministers treat students who are ‘loyal but indignant’ today when one compares them with the Manchu-Qing court of 120 years ago? 比較120年前的滿清時代,現在的大人先生們如何對待「忠憤迫切」的青年學生?

Two Wuxu Years have come and gone. Recently, [with the news that the Chinese Constitution would be revised to allow ‘a national leader’ more than two five-year terms in office as president of the People’s Republic] this [Spring Festival] couplet appeared on the mainland internet: 兩個戊戌之後,大陸網上有人貼出以下對聯:

1.4 billion people,

All have eyes to witness;

Eighty million masses,

No real man among them.

十四億民,

都有兩眼作看客;

八千萬眾,

竟無一人是男兒。

The horizontal line at the top [which sums up the message of the couplet] reads: 橫額是

Year of the Dog Constitutional Change

戊戌憲變

‘Eighty million masses’ refers to the eighty million members of the Chinese Communist Party.「八千萬眾」是指中共黨員人數。

***

— 李怡, 世道人生: 戊戌男兒, 2018年3月1日

Lee Yee Facebook

More Essays on the Apotheosis:

- 1 October 2017 — The Best China, China Heritage, 1 October 2017

- The Ayes Have It, China Heritage, 18 October 2017

- Lee Yee, What’s New About Such Thinking? (The Best China, II), China Heritage, 5 November 2017

- Lee Yee, The Unbuilt Wall of Sorrow — on the centenary of the Russian Revolution (The Best China, III), China Heritage, 7 November 2017

- Lee Yee, Who’s on First — China’s Successive Failures (The Best China, IV), China Heritage, 20 November 2017

- Lee Yee, China Bound — meeting and eating (The Best China, V), China Heritage, 15 December 2017

- Lee Yee, Hollow Men, Wooden People (The Best China, VI), China Heritage, Christmas Eve, 2017