Watching China Watching (XXIV)

This is one of three essays concerned with living in the New Epoch of Xi Jinping and the party-state of the People’s Republic of China. The following speech-turned-essay (‘蘊 — What Is & Isn’t Possible’), and ‘Staying Out of Range 彀外遺少’, which will appear on 25 May 2018, were published in 2008 and 2009 respectively. They are re-issued here as companion pieces to Contentious Friendship — Watching China Watching (XXI), China Heritage, 29 April 2018, to mark a decade since the redefined concept of zhengyou 諍友, ‘the candid friend’, was articulated.

As China prepared for the 2008 Olympic year, to some observers the enhanced surveillance and policing measures being pursued by the authorities were a clear indication that the security state would be the norm in the post-Olympic era. Economic successes had further enabled the Communist Party and for years it had been working to combine its traditional Leninist political practices with an evolving (and expanding) ethos of cultural and territorial nationalism. With the rise to power of Xi Jinping from late 2012, it was also evident that a reinvigorated Party orthodoxy backed up by the kinds of wealth and power long dreamed of in the Chinese world, would pose dangerous challenges to advocates of independent politics, thought, scholarship and action.

It should be obvious from these essays that the advocacy of the stance of zhengyou was not some canny tactic that would allow people to get away with saying undiplomatic things in a culturally nuanced way. It was, and remains, a defense of individual conscience and behaviour in the face of autocracy.

***

As I noted in a speech made when launching China Heritage in December 2016:

Over the years, I have experience three China climacterics, each a decade apart: 1979 which saw the arrest of Wei Jingsheng and the promulgation of the Communist Party’s Four Cardinals Principals; 1989 and the nationwide Chinese protest movement crushed on June Fourth; and, Christmas Day 2009, when Liu Xiaobo was sentenced on trumped up charges. Today, I have spoken in sombre tones about the present, but although I might not outlive the reign of Xi Jinping, or the pitiful careers of many of the mediocrities who crowd the stage, you, at least most of you, probably will. You should prepare now and, in the years to come, for that future as well; it is to that end that I’ve addressed you as I have.

Hegel famously remarked that: ‘The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.’ That is, wisdom — the owl of the goddess Minerva — only fully takes flight or unfolds after the fact. But for us it is still daytime; it is a day that began with the morning sun of promise. Although it is too early to tell what time of day it is now, there is no doubt that it will — as do all things — draw to an end. The lengthening shadows of dusk — recalling the shade from Lu Xun with which I started this talk — will then offer a measure of wisdom and a better understanding of the world in which we are now living.

— from Cutting a Deal with China

***

The following essay was revised on the basis of a speech presented at the ‘What’s Possible?’ workshop on contemporary Chinese art organised by the curator Huangfu Binghui 皇甫秉慧 and sponsored by Zendai MoMA in Shanghai on 20 April 2008. Some material from the revised text has also appeared in Worrying China & New Sinology. Minor emendations have been made t0 this updated version.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

21 May 2018

蘊 — What Is & Isn’t Possible

Geremie R. Barmé

‘What’s Possible?’ is a question that can best be responded to in the light of what has been possible, as well as in relation to what potential existed for past possibilities to become present reality. What has been possible reveals how the potentialities of the past have been realized and form the contingencies for ‘that which has not yet come’ 未來.

The possible unfolds also in the context of that which is probable. What is probable says much, perhaps too much, about what could, but probably will not, be. It can too readily foreclose futures before their time to be has come. The possible can also take flight on the wings of that which is impossible.

The impossible is that on which the creative mind dwells, aspires to and by which it is frustrated. The impossible also forms the backdrop to the activities of cultural tricksters, and shysters. If the impossible is not the basis for the possible, then potential will remain just that, and remain unrealized.

The following remarks are grounded in my work on Chinese culture and thought dating from the 1970s. Allow me to reflect on the possibilities of that past and how they appear in our present, and what this may tell us about what may possible from here.

The Art of the Impossible

I would like to open my remarks with a reflection on recent events, taking for my title a few words from the Czech playwright and politician Václav Havel, who wrote about the art of the impossible and politics as morality. I do so because I believe that at a time of dyadic conflict and escalating discursive violence to discuss art, culture and the possible, it is helpful to reflect on how language not only imprisons, but can also enable.

On Wednesday last week — 9 April 2008 — Kevin Rudd, the Prime Minister of Australia, addressed an audience at Peking University, China’s preeminent tertiary institution. He chose to talk to the students about the broad basis for a truly sustainable relationship with the economically booming, yet politically autocratic state that is China.

First Rudd acknowledged where he was: at a university that has more than any other educational institution in China helped shaped that country’s modern history; one known for its contributions to Chinese intellectual debate, political activism and cultural experimentation. He mentioned some of China’s twentieth century intellectual heroes and exemplars whose careers were entwined with Peking University. Some were involved in reshaping Chinese into a modern language — baihua wen 白話文— capable of carrying urgently needed political, cultural and historical debate. One was a leading democratic thinker: Hu Shi 胡適. He also made three references to Lu Xun (魯迅, d.1936), China’s literary hero, and unyielding critic of authoritarianism and principled dissenter, noting that Lu Xun personally designed Peking University’s crest. It would not have been lost on his audience that the PM’s choice of intellectual exemplars acknowledged China’s dominant Communist ideology (he also chose to mention Li Dazhao 李大釗 and Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀) while pointing to the traditions of free speech and debate that have made Peking University so important.

Rudd’s strategy was thus first to honour the place where he was speaking and its connection to significant, complex, historical and cultural figures. He went on to speak more personally of his own educational and political trajectory, and about Australia’s national interest. Appealing to his youthful audience to consider what positive role they could play in China’s rise as a world power, he evoked the concept of ‘harmony’ 和諧, embraced by the current Chinese leadership, before making a canny digression. This was to note that 2008 is the 110th anniversary of the Hundred Days Reform Movement of 1898, during which an enlightened ruler, the Guangxu 光緒 Emperor, struggled to enact a process of political reform and modernization similar to the Meiji Restoration in Japan that had taken place not long before. Rudd didn’t need to say that this movement failed and its leaders were beheaded; his audience would know that. Instead, he noted that one of the leading lights of the reforms, the thinker Kang Youwei 康有為, who survived by fleeing into exile, went on to write about ‘the Great Harmony’ 大同, that is, ‘a utopian world free of political boundaries’. Thus, in a manner both subtle and eminently clear to a Chinese intellectual audience, he linked the officially approved concept of ‘harmony’ to the broader course of political reform, change and openness.

Rudd then spoke about China joining the rest of humanity as ‘a responsible global stakeholder’ — a lead-in to address the pressing issue of Tibet. By framing his comments in such a manner, he established his right — and by extension that of others as well — to disagree with both Chinese official and mainstream opinion on matters of international concern. There is a venerable Chinese expression for this position: ‘A true friend,’ Rudd went on, ‘is one who can be a zhengyou, that is a partner who sees beyond immediate benefit to the broader and firm basis for continuing, profound and sincere friendship.’

The subsequent Chinese media discussion of Rudd’s use of the powerful and meaning-laden term zhengyou 諍友 — the true friend who dares to disagree — has been considerable. That is because the more common words ‘friendship’ 友誼 and ‘friend’ 朋友 have formed the cornerstone of China’s post-1949 diplomacy. Mao Zedong once famously observed: ‘The first and foremost question of the revolution is: who is our friend and who is our foe.’

To be a ‘Friend of China’, the Chinese people (a nebulous and abstract collective), the party-state or, in the reform period, even a mainland business partner, the foreigner is often expected to stomach unpalatable situations, and keep silent in the face of egregious behaviour. A Friend of China might enjoy the privilege of offering the occasional word of caution in private; in the public arena, however, he or she is expected to have the good sense and courtesy to be ‘objective’, that is to toe the line, whatever that happens to be. The concept of ‘friendship’ thus degenerates to become little more than an effective tool for emotional blackmail and enforced complicity.

Kevin Rudd’s tactic was to deftly sidestep the vice-like embrace of that model of friendship by substituting another: ‘A strong relationship, and a true friendship,’ he told the students, ‘are built on the ability to engage in a direct, frank and ongoing dialogue about our fundamental interests and future vision.'[1]

These are the words of a consummate politician, but they are also words that I believe enable broad cultural engagement and discussion of the possible at a particularly fraught time. I offer these reflections as a prelude to the following, simple observations.

蘊 Yun

As Kevin Rudd used the culturally rich Chinese expression zhengyou to offer a more robust ground for positive and challenging exchange between China and its Others, in these comments I suggest the word yun 蘊 as one that allows me to explicate the topic of our gathering ‘What’s Possible?’

Yun is one of those multifaceted terms that abound in Chinese. These are words with ancient origins far pre-dating the Christian era, and which through different uses and changing circumstances have, over the centuries, gathered layers of meaning, sediments of significance. Yun can signify to gather, contain, collect, hoard and store. In early translations of Buddhist texts it was used to translate the Sanskrit term skandha स्कन्ध, the wuyun being the ‘five aggregates’ or constituent elements of existence. Its other extended meanings cover such concepts such as dissatisfaction and ire.

作為積聚意義,《後漢書 · 周滎傳》有:蘊匱古今,博物多聞。

作為深奧意義,《宋史 · 範祖禹傳》有:平易明白,洞見底蘊。

作為郁怨意義,《後漢書 · 王符傳》有:志意蘊憤,乃隱居著書三十餘篇。

至於現代用法,不外:蘊含、蘊蓄、蘊藏、藴藉之類。

Of these, perhaps, the most relevant for my modest purpose today is a usage from the Song Dynasty, around the tenth century, in the expression diyun 底蘊: concealed possibility or inner sentiment; as it is put in modern Chinese: 蘊藏的才識或修養. It also means 內情或蘊藏的內容. Diyun is still used — often as a description of an aesthetic quality in an artistic work — in the sense of resonance or layered depth. To be without diyun is to be shallow, derivative and evanescent [in recent times, Xi Jinping and his propagandists articulate their view of the Chinese multiverse in terms of a narrow ‘cultural diyun‘ 文化底蘊 — Ed.].

Non-official Chinese art, and the broader cultural world, of the 1980s is something about which I have written at length. The potential of the 1970s and 80s, an era when the frustrated or misdirected creative energies of high Maoism found expression through new generations and new cultural forms, was undeniable, its products powerful and promising. We saw the enthralling potential of filmmakers, writers, thinkers, artists using all media, and the times were gravid with possibility.

Around that time — in 1988, as I recall — I wrote for the Hong Kong press a Chinese essay about yang shalong 洋沙龍, the ‘foreigner salons of Beijing’, those apartments, embassies and rented spaces where patrons would give their discovered Chinese artists and writers a chance to be seen, heard and most importantly to sell to visitors, be they curious tourists or well-connected travelers. I noted the political economics of that particular world, one in which the overt authoritarian control of culture led to the rise of parallel cultural creators pursuing foreign support, protection, investment and validation. That ‘cultural shadowland’ could, in many ways, be understood through the light application of a popular Maoist term for the past as being ‘semi-colonial’ 半殖民化. [See 白杰明, 北京的洋沙龍,《九十年代月刊》,1988年3月] I would suggest that even now, despite the breath-taking developments of the past decade, the marketisation of Chinese art, its global éclat, and the maturation of markets, galleries and the critical environment, traces of that post-Maoist ‘semi-colonial’ era remain in evidence. Now, however, Chinese creators are joined more equally by Chinese buyers, commentators, and curators to redress past imbalances, and the party-state too takes its cut.

Those of you who are familiar with my writing on Chinese culture in the 1980s and 90s may recall my sentiments when discussing Chinese art as ‘big business’. Among other things, when contemplating the particular cultural economics of the non-official Mainland arts I wondered whether ‘without the impotent interdictions and papal bulls of the official mainland overculture, how viable would any of the alternative work of the “counterculture” really be? … [A]rt… gains much of its visibility only when set against the gloomy backdrop manufactured by the state’.[2] During that period, while business was still at the heart of the art trade, the moral dimension of the discovery and promotion of some Chinese artists was undeniable. The acceptance of ‘Chinese art’ as a viable international brand that is now a prominent feature of the trade in cultural production has realized the potential of numerous Chinese artists and makes possible wealth and fame for the select few among the clamouring masses of artists who crowd the new salons of Beijing, Shanghai and other cities.

Naturally, for the dealers, curators and gallery owners, Chinese and non-Chinese who now flourish along with the ever-multiplying ranks of contemporary Chinese art producers, the brash efflorescence of the art market is something that demands celebration. For many it is another landmark in China’s coming of age, its arrival as a cultural force on the international stage. Some Chinese artist and works are also, for the time being, a great investment.

The Potential of No Name

The reason I accepted Huangpu Binghui’s invitation to address this gathering has a great deal to do with the exhibition mounted by Zendai MoMA in June-July 2007 of the No Name artists 無名畫會, curated by Gao Minglu 高明潞.

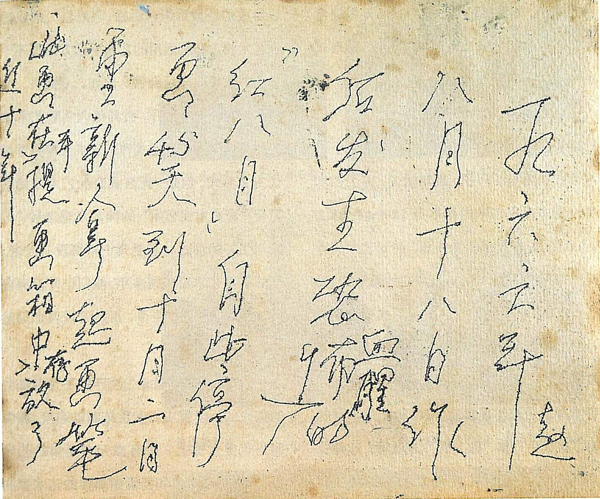

I believe this was a major event in the story of modern and contemporary Chinese art. I first met members of the No Name group in the 1980s, and saw scattered examples of the lyrical works that they made in the 1960s and 70s. These were artists who, mostly, pursued their work around the old city of Beijing, in particular around Hou Hai 後海 a quiet and forlorn place of grace, fallen on hard times (although now known as a tawdry bar area). Using the rudimentary art supplies available to them they created a world of the spirit, a world of possibility. Perhaps in the context of the hysterical ‘red noise’ 紅色噪音 that surrounds us today, it is worth mentioning Zhao Wenliang’s 趙文量 simple oil painting of a stretch of wall at Changling, the tomb of the Ming Yongle Emperor, who built the modern city of Beijing in the 1410s. The painting was made at the height of summer, as the verdure in the images suggests. You can nearly hear the clamour of the cicadas. On the reverse of the image, Zhao Wenliang laconically notes the date. It was the 18 August 1966. That was the day that Mao Zedong reviewed the first mass rally of Red Guards in Tiananmen Square at the launch of the Cultural Revolution.

The No Name artists would continue to meet, talk about art and pursue their diverse personal visions. Theirs was an era now evoked as a low-point in Chinese cultural history, freedom of expression and human potential. The No Name artists could not have imagined a future of the Stars, or post-89 art, and possibly they would be surprised that their extraordinary, if understated, achievement, would go all but unnoticed until 2007.

Others, of course, still see in the theory although not necessarily the practice of the Cultural Revolution era great potential for social and cultural possibility in the future. Some would argue that the post-Mao art of China can only be understood in the context of that era. To an extent, I would agree. However, the No Name artists pursued their disparate visions with little thought of immediate (or even long-term) gain, recognition or influence. I would suggest that their work is testament to the power of possibility.

I would wonder, for the sake of our present discussions, how today the practice of creating brand-name artists, the treadmill of the international biennial circuit, the factory-scale production of art by teams of artisans working at the beck and call of the celebrated artistic maestro, how the galleries of influence and the collectors with capital support suborn and direct potential through their activities, praiseworthy though they may be, also occlude, or frustrate, other possibilities.

The writer Lu Xun mentioned his own perception of the possible above, which I have suggested with the term yun 蘊. After all, he and his fellows founded a literary group called the Weiming She 未名社. It is a name often mistranslated as either ‘The Unnamed Society’ or the ‘No Name Society.’ In reality, as Lu Xun himself pointed out, it was an artistic collective that was ‘yet-to-be named’. The group’s main aim was to translate and publish international literature to help feed the cultural renaissance and the possibilities of the 1920s.

During the high Maoist era, the multifarious stories of individuals were submerged in the larger story of Mao’s own revolutionary history, and that of the Communist Party’s march to ever-victorious achievement. The myriad of complex, nuanced, conflicting and disturbing tales of individuals that did not fit into the mainstream narrative went untold, or were silenced.[3] Since then, while a few comfortable individualized stereotypes of suffering and forbearance have come to represent most of Maoist-era history, other more layered and alternative accounts also exist, discomforting and inconvenient.

In China, the dominant narrative of the party-state, and the results of its sagacious policies that mix its hegemony, elements of resuscitated Chinese tradition with neo-liberal reform and constant twitterings of nationalism, allows it to maintain its unassailable purchase in the media, textbooks and popular accounts. The stories that people tell themselves, stories that nations tolerate — or, in some lucky cases, encourage — so that their citizens can imaginatively engage with the past and create a future, are but fragile narratives. They are all-too-easily curtailed by the story that power-holders like to tell themselves, while making everyone else listen to them. Over time, mute acceptance or unreflective parroting become the norm. If such a situation pertains, what can truly become possible in the life of many individuals or their community must, to a greater or lesser degree, shimmer only in the realm of the potential.

Landscapes in a Room

The inventiveness of the creative mind finds possibility in many locales. One of these is the studio, the private space, or the retreat. Many young people are now what the Japanese years ago called o-taku-zoku お宅族. In Chinese, they are zhainan 宅男 and zhainü 宅女. These are the young men and women who, as my artist-friend in Hangzhou — Geng Jianyi 耿建翌 (d.2017) — describes them, were the singular product of the unstinting love and devotion of six people: their parents and two sets of grandparents.

Freighted with the hopes, dreams and demands of two familial generations generated by the pitiless politics of the past, many of these young people, in particular the sensitive, quirky, rebellious and even obnoxious among them often attempt to disengage entirely from their immediate surroundings. Their phobias — real or imagined — are legion: the cement cityscapes of their hometowns, the noisy congestion of every avenue of escape, the alienation from ‘mainstream opinion’ 主流民意, an education system that is proscriptive, draconian and uninspiring, and a media world clogged with raucous advertisements and guided thought… . The list goes on. For the creative and talented the art world too has luster, and yet also causes revulsion.

The cynical two-way exploitation of the international art market discussed above (and its own calculated and canny embrace of Chinese art) confirms the hauteur growing since the 1990s.

I would also venture that despite one’s best efforts it is nigh on impossible to calculate what would really be possible in a cultural and intellectual environment if circumscription and self-policing were not the norm. That is not to say that there are not many who think as freely as possible, and have created work in a myriad of unfettered ways in recent years. But I would suggest that we do not, and cannot yet know, what other creative possibilities would come about if any and all that could be imagined were possible in the lived realities of today’s China.

***

In the 1980s, the once-misty poet Yang Lian 楊煉 wrote of his own life in a room. He did so in a poem about a relationship and betrayal, but it also spoke to its time: 1987. That was a time when the first modern Chinese student demonstrations calling for the freedom of the press led to a political purge and, among other things, the ouster of the Communist Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦. My friend and colleague John Minford and I used it in the revised and expanded edition of our study of 1980s non-official culture, Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience.[4]

I will end my remarks with some lines from that poem as translated by John Minford:

Landscape in a Room

Yang Lian

Thirty-two, I’ve heard enough lies

No more landscapes can move into this room

Visitors with corn-cob faces

Stand at the door hawking crumbling rocks

Sticking out their coated tongues,

Eternity ground between teeth

…

Until the last bird flies skyward, escaping

Colliding in that hand

frozen into a blue vein

Where you have locked yourself

There will remain

an empty echo

Reciting darkness

Burying the only landscape in your heart the only

Lie

房間里的風景

楊煉

三十二歲 聽夠了謊言

再沒有風景能夠移進這個房間

長著玉米面孔的客人

站在門口叫賣腐爛的石頭

展覽舌苔 一種牙縫里磨碎的永恆

…

直到最後一隻鳥也逃往天上

在那手中碰撞 凍結成藍色靜脈

你把自己鎖在哪兒

這房間就固定在哪兒 空曠的回聲

背誦黑暗

埋葬你心裡唯一的風景唯一的

謊言

Notes:

[1] For more on this, see Contentious Friendship — Watching China Watching (XXI), China Heritage, 29 April 2018.

[2] See my In the Red, on contemporary Chinese culture, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p.206.

[3] See my ‘Sang Ye’s Conversations with China’, the introduction to Sang Ye, China Candid: the People on the People’s Republic, edited by Geremie R. Barmé with Miriam Lang, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

[4] Geremie Barmé and John Minford, Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, New York: Hill & Wang, 1988, 2nd ed., pp.398-399.