Watching China Watching (XXV)

On 26 August 2016, Zhang Peili: From Painting to Video, an exhibition of the video art of the Hangzhou-based artist Zhang Peili 张培力 opened in the gallery of the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW). The show included one of Peili’s earliest, and most famous, video works, Water — Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary 水——《辞海》标准版.

In the lead up to the exhibition, Olivier Krischer, one of the curators of the show who knew I had followed Peili’s work since the mid 1980s, invited me to write on his art for a proposed publication. During our discussions, I mentioned the significance of radio broadcasts, both in China and Australia, up until the 1990s. Olivier suggested that I might like to discuss Peili’s Water video in relation to that subject. We ended up with the following ‘unreliable memoir’ (pace Clive James), ‘Something In The Air’.

As part of the opening of the Zhang Peili show, the photographer Lois Conner, whose work features in the masthead of China Heritage and frequently graces these virtual pages, presented CIW with ‘Flying Machine 飞行器’, one of a pair of oil paintings that Peili made in 1994. They were his last paintings and that powerful work now features in the CIW building (as do many works by Lois herself). The building is also a work of art, designed by another mutual friend, the Beijing-based architect Gerald Szeto 司徒左.

***

A shorter version of this essay appeared in China Channel of the Los Angeles Review of Books on 4 June 2018, a date of great significance for China, and for the rest of the world. The author would like to thank Nick Stember of China Channel for his editorial suggestions. Simplified Chinese characters are employed here as they better reflect the atmosphere of the era described in the essay.

— The Editor

China Heritage

8 June 2018

***

Related Material:

- Gerald Szeto, The Architecture of Education in Canberra and Beijing, Fourth CIW Annual Lecture, 5 May 2014 (for a video recording of the lecture, see here).

- 1-5 May 2014: A Building, Two Films, an Exhibition, Two Lectures, a Podcast and Two Performances, The China Story, 13 May 2014

- Geremie R. Barmé, CIW: Opening a Building, The China Story, 30 October 2015

- Geremie R. Barmé, The Affinities of Art 藝海因緣, China Heritage, 26 August 2017

- Olivier Krischer and Kim Machan, curators, Zhang Peili: from Painting to Video 张培力:从绘画到录像, 27 August-15 December 2016

- Zhang Peili, 语言与语境 / Text and Context, translated by Linda Jaivin, 25 August 2016

- Interview with Zhang Peili on Flying Machine (1994)

- Geremie Barmé, China’s Art of Containment, The New York Review of Books NY Daily, 27 November 2017

- Geremie R. Barmé, One Decent Man, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018, vol.64, no.11

Something In The Air

Geremie R. Barmé

Enemy Broadcasts

Tōutīng dítái!

偷听敌台!

The gruff voice barked over the cement trough. It was early morning and I was in the washroom of our dorm building at the Beijing Foreign Languages Institute brushing my teeth. He was a Worker Peasant Soldier Study Officer 工农兵学员 (the Maoist term for ‘student’) wearing, even at that darkling hour, a high-collar blue Mao jacket. Steely faced, his tone was both a warning and an accusation. I had no idea that he’d just said:

‘You’re sneak-listening to enemy broadcasts!’

It was October 1974. I’d come from Australia a few days earlier, a naïve and eager exchange student who had only studied Chinese for two and a-half years. I’d put my small radio — listening to which I hoped would help improve my language comprehension — on the dividing ledge of the trough in the sparse washroom and had tuned in to a station with a newsreader I could just about believe that I understood. He wasn’t reading news in the shotgun harsh staccato, or at the seemingly impossible speed, that was blaring out of every loudspeaker in our dorm and around campus. The delivery was nearly dulcet in tone and I presumed that this milder voice must be coming from some local station or even a provincial broadcaster that chose for their newsreaders the style of clear and calm Chinese that I was used to from classes at The Australian National University.

Sūxiū guǎngbō!

苏修广播!

My grim-faced interlocutor spat:

‘Soviet Revisionist radio!’

Our teachers had introduced us to basic Maoist Chinese. In our third year, as we were gradually inducted into the use of the Simplified Chinese Characters promoted in the People’s Republic of China, we’d also painstakingly read through articles from the Communist Party’s Red Flag magazine, the standard bearer for ‘theoretical’ articles and more general gumpf from the People’s Daily. Our more earnest reading was devoted to deciphering articles from the Hong Kong and Taiwan press in a Chinese that reflected a more-or-less real world. But, from my high-school years I’d been leafing through the English-language Peking Review and studying the Language Corner in other Beijing propaganda publications, so I already knew the basics: American Imperialism 美帝, Soviet Revisionism 苏修, Counter-revolution 反革命, Chiang Kai-shek Bandits 蒋匪, as well as the Three Oppressive Mountains 三座大山 spoken of by Chairman Mao 毛主席: Feudalism 封建主义, Capitalism 资本主义 and Semi-colonialism 半殖民主义. Although, as a foreigner I had by definition been listening to ‘enemy broadcasts’ my whole life, I didn’t know the expression dítái 敌台 that my new Beijing school mate had growled. Now I’d never forget it.

It was in high school in Sydney that I’d first been exposed to People’s Radio. One of my friends at Randwick Boys’ High was Samson Voron, a ham (amateur) radio enthusiast. We were both ‘Trekkies’ avant la lettre; Samson even had the look of a youthful Spock, his Russian ancestry giving him the smooth features and eyes (but not the pointy ears) of the laconic science officer of the Starship Enterprise. Sam couldn’t fly a spaceship or teleport to other worlds, but long hours spent scanning the airwaves at night brought him as close as possible to being a terrestrial global citizen.

Even in those jejune years Samson knew that I was drawn to Taoism, Tibetan Buddhism and Indian mysticism; he thought I’d probably be interested in the bizarre world that came streaming into his earphones via Radio Peking which, along with Radio Moscow, was one of his favourites in that age of youthful rebellion. During morning recess one day, he told me about the shrill hysteria of the Radio Peking announcers. It was 1967; I was thirteen, and it was the height of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Samson invited me home to hear for myself. It was hysterical stuff, we thought it was like listening to a Chinese version of The Frost Report, a popular satirical TV show from the UK. Some of David Frost’s performers would go on to create Monty Python’s Flying Circus, but I was drawn to the surrealism of the People’s Republic of China in real time. Samson encouraged me to write to Peking because, he told me, they’d send me publications free of charge. From then until I went to Beijing as an exchange student in 1974, I received a regular flood of printed matter: the weekly Peking Review 北京周报 and copies of the monthly China Reconstructs and China Pictorial. I was attracted to the surreal, touched-up images of workers, peasants and soldiers in the magazines, as well as the Chinese Language Corner, but Peking Review, which clogged up our mailbox much to the bewilderment of my parents, and which was printed on impossibly thin dictionary paper, was a challenge: each issue started with long reports on meetings of the Chinese Communist Party, mass rallies in Tiananmen, details of Chairman Mao fêting obscure foreign Communists, wordy theoretical screeds on the Cultural Revolution… And it was all couched in an English prose that was by turns impenetrable and risible. It was my introduction to what, nearly forty years later, I would write about as New China Newspeak 新华文体.

Unless Samson invited me over to his place I hardly ever got to hear Radio Peking, and even then there was only so much news in a disconcertingly plummy English accent about political victories and production statistics that could hold the interest of a couple of fourteen-year olds, no matter how nerdy we were. My interest in China, philosophy, politics and history, however, burgeoned. Later, as a student in Canberra I was drilled in clarion northern pronunciation by our tutor Vieta Dyer (Svetlana Rimsky-Korsakoff Dyer), a native speaker of Chinese who was born in what was then called Beiping; we were only introduced to the more modulated tones of Taiwan-inflected Mandarin the year after. The contrast couldn’t have been greater so when, in late 1974, I heard that stern voice admonishing me in the washroom in Beijing, I had no doubt about the tone, and the demeanour, of Official China.

A Measured Life

As students in a late-Cultural Revolution university, our lives were marshalled by the radio. At 6.00am every day the loudspeakers crackled to life with a rousing broadcast that exhorted us to go jogging and to take part in group callisthenics. The collective PE routine was the fifth in a series of radio exercises first introduced in 1951. Known as the ‘Cultural Revolution Callisthenics’, the exercises were prefaced with the words:

Our Great Leader Chairman Mao Has Instructed Us To:

伟大领袖毛主席教导我们:

‘Enhance Physical Education 发展体育运动;

‘Improve the People’s Strength 增强人民体质;

‘Be On High Alert 提高警惕;

‘Defend the Motherland 保卫祖国!’

News programs were shouted into the canteens while we ate; morning classes were interrupted by further broadcast callisthenics; lunch was midday news and warnings about the shifting tide in class struggle; afternoon broadcasts replaced tea time and the evening meal was ushered in by further news and updates on the state of the revolution. The press would feature them in bold typeface, but in the broadcasts key quotations from Chairman Mao were incanted with a particular cadence. These were invariably followed by the reading out of editorials that would appear in the press the next day, including long and turgid articles on topics as various as ‘Bourgeois Rights’ 资产阶级法权 (the precursor of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign of today) and ‘Capitulationists’ 投降派 in the Ming-dynasty novel The Water Margin 水浒传, as well as the invariable denunciations of the Soviet Revisionists 苏修. On top of all of that, there were the daily mind-numbing reports on the cavalcade of foreign dignitaries hosted by the revolutionary leadership, as well as lame student essays shouted out on the school PA system that mimicked in tone and style the official line on any given topic. Punctuated with martial music and rousing exhortations, radio broadcasts measured out our days and echoed through our dormitories, classrooms, and over the sports fields.

When I came top in the year in English one year in high school, I’d requested as my prize a copy of The Selected Poems of T.S. Eliot. In my world-weary adolescence an early favourite was The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock:

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?

The verse would haunt me as clockwork broadcasts punctuated and filled student life in Maoist China.

Diminishing Returns

My fascination with listening to radio broadcasts decreased in proportion to my comprehension. At the time, I couldn’t have known that we were living through the End Days of High Maoism, a two-decade-long period that began with the Hundred Flowers Movement of 1956. During that campaign people from all walks of life had been lured into ‘helping the Party improve its work style’. Those who spoke out were in turn denounced as enemies of the Party and, in many cases, sent into internal exile. It would all only come to end first with the demise of Mao, on 9 September 1976, and the formal rejection of his class-struggle-based policies in December 1978 in favour of economic reconstruction.

Our textbooks, the novels and comics we read, the newspapers we studied, the radio we listened to, the lectures of our teachers and the conversations of our Chinese classmates all reflected the mono-Maoist world. In their disparate ways they all found voice in an unforgiving and relentless Sino-logorrhoea, the English version of which I had first heard on Sam’s shortwave radio as a thirteen-year-old high school student in Sydney.

Real enemy broadcasts — the BBC and Radio Australia — became a guilty pleasure and we foreign students listened in enthusiastically, if guardedly. As there were no students from the United States (although they would come soon enough, trailing their clouds of glory) until after the formal Sino-US rapprochement of 1979, the Voice of America was simply not on our dial. Only later would I learn that VOA, along with Radio Australia were staples for Chinese radio listeners and enthusiasts (although VOA was jammed until 1976). In fact, Radio Australia, with the proximity of its shortwave transmitters and its mix of light news and even lighter music, enjoyed a prominence and cultural status in China in the 1970s and 1980s that is now impossible to imagine.

On 5 April 1976, a day that marked Qingming 清明, the traditional festival commemorating the dead, mass protests against Mao Zedong and his allies in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, were ruthlessly crushed. Tension had been building for days, and even in far off Shenyang we knew from the radio news and newspaper reports that major events were unfolding. I had developed a hesitant friendship with my roommate, a young cadre who had previously worked in propaganda (Chinese roommates had been allocated to our dorms on the basis of their political reliability). On the night of 5 April, as the news about what was then denounced as a ‘counter-revolutionary incident’ in Beijing was being broadcast, my roommate opened up and said that he thought it was time he helped me understand what was really being said. That night, and over the subsequent months, he taught me how to ‘reverse-listen’ to the news and ‘reverse-read’ the newspapers. Today, you’d probably call it ‘reading against the grain’; anyway, I was slowly inducted into the refined socialist art of ‘reading between the lines’, a talent that countless citizens of China’s People’s Republic had acquired for the sake of their own wellbeing during the long years of Maoism. Working in Hong Kong from 1977, I would also learn about China News Analysis and the dogged cadre of listeners, readers and analysts led by László Ladány SJ. As Simon Leys (Pierre Ryckmans, my undergraduate lecturer in Chinese), an avid reader of that newsletter, observed:

What made China News Analysis so infuriatingly indispensable was the very simple and original principle on which it was run (true originality is usually simple): all the information selected and examined in China News Analysis was drawn exclusively from official Chinese sources (press and radio). This austere rule sometimes deprived Ladány’s newsletter of the life and colour that could have been provided by less orthodox sources, but it enabled him to build his devastating conclusions on unimpeachable grounds.

***

In October 1976, only weeks after Mao’s death, our class of foreign students was sent on another ritualistic round of ‘open-door schooling’. This policy had been introduced during the Revolution in Education that was supposed to bring book- and classroom-bound students into closer contact with lived, productive reality by assigning everyone at university to work in people’s communes and factories during term time where they could learn from real workers-peasants-soldiers (on the grounds of national security foreign students were barred, however, from military units).

It was autumn and our entire class at Liaoning University in Shenyang, where I was studying after a year at Fudan University in Shanghai, was sent to work on an apple-producing commune in Jin County on the Liaodong Peninsula, not far from Dalian. During the day we picked apples with the local peasants; at night we were sequestered in a separate, but still collective, dormitory. With little diversion and no entertainment we often listened to snatches of radio news and music on Radio Australia. This is how we first heard reports that a group of leaders in the Communist Party Politburo had been detained. It was explosive information, and it was punctuated by obvious military movements taking place around us as army planes flew overhead. We later learned that the air traffic corridor connecting the Shenyang Military Region to Peking was overhead; everyone was alarmed. Meanwhile, the Chinese broadcasts shouted into our dorms, following us into the commune village and out into the fields, spoke in riddles. The main message was, literally, gnomic: a tirelessly repeated mantra that called on the nation to persevere with the ‘Three Embraces and Three Rejects’ 三要三不要:

- Embrace Marxism, Reject Revisionism 要搞马克思主义,不要搞修正主义;

- Embrace Unity, Reject Disunity 要团结,不要分裂;

- Embrace Openness, Reject Plots and Intrigue 要光明正大,不要搞阴谋诡计。

In the capital, party leaders were hard at work suppressing news of the downfall of a group that would soon be known as the Gang of Four for the two months they estimated that it would take to round up their henchmen (and henchwomen). Professionally trained to be sensitive to every nuance in China’s political life, however, our teachers and cadre-minders knew something momentous was afoot. We told them what we had heard on Radio Australia and in immediate confirmation of the accuracy of the news they locked us in our dorms. They were worried that the news from the enemy broadcasts might foment a local incident. Meanwhile, they dispatched a delegation back to Shenyang to ascertain what was going on. News of the arrests of Jiang Qing, Mao’s widow, and her cohort, had been leaked to the Western media, and on 14 October Party Central was forced to announce what was in effect a coup d’état.

The teachers and cadres who stayed back with us in the commune now fitfully revealed their disdain for what was being openly denounced as a plot to usurp the party and suborn the revolution in the name of Chairman Mao. By the time we were taken to the port city of Dalian — a reward for our austere weeks working on the commune (although we were now expected to participate in a formal celebration of the ouster of the Gang of Four) — at the end of October, our local Chinese leaders had accommodated themselves to the latest direction in national life. They were doing what can best be described as a ‘dialectical backflip’ to justify their previous compliance with, and even enthusiastic imposition of what was now a discredited political line. They had always reviled the members of the newly minted ‘Gang of Four’: Jiang Qing 江青, whose speeches on literature we had previously been obliged to study, was a shrill and scheming bitch; no one trusted Zhang Chunqiao 张春桥, an obtuse theorist who looked positively evil; that pretty-boy Wang Hongwen 王洪文 was an ambitious Shanghainese nobody; and, that pumped-up literary critic Yao Wenyuan 姚文元 was just another shifty intellectual.

Air Letters

Radio broadcasts ruled the airwaves of China and it was through the radio, more than via any other medium, that the shifting political winds of China’s revolution were communicated to the country.

In early June 1966, a letter from Chairman Mao read over the radio announced his support for a group of high school students calling themselves the Red Guards 红卫兵. A radio broadcast in mid August that year reported on a mass rally in Tiananmen Square in which the leadership called on the nation to ‘Smash the Four Olds’ 破四旧, which lead to an hysterical wave of iconoclasm. And itt was over the radio that every convoluted twist and turn in the progress, as well as the denouement, of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was first announced.

The authoritative voices came from Central Peking Radio, but their message was relayed by countless provincial, municipal and local stations, as well as via the small-scale broadcasters in every factory, commune and school. You might be ignorant of the secretive internal communications of the Party, you might mindlessly recite Mao Thought, sleep (or knit) through the imposed political study sessions and avoid reading the daily press, but there was no escape from the broadcasts: they were as incessant as they were insistent and ubiquitous.

(It was only many years later, in the late 1990s, when I was working on the film Morning Sun with my colleagues at the Long Bow Group in Boston, that I learned that in mid 1966 a particularly hysterical tone came to exemplify Cultural Revolution public speech, and broadcast news, in part because Jiang Qing was jealous of a young Red Guard Mao had shown some interest in. But, that is a story for another time.)

It was on the airwaves that the Party would declare the end of the era of Maoist extremism, giving notice that a new age was dawning for the People’s Republic. In an time of media control and lingering fear the people who spoke out more freely, or who simply traded rumours (political, personal or sexual), were known as ‘mini broadcasters’ 小广播站.

It was also in those years that, in passing, I encountered a recent jailbird: Sidney Rittenburg. He cut a slight figure, steely but grey from nearly a decade in gaol. Friends who had been present, reported that some years earlier they had heard Premier Zhou Enlai declare Rittenberg to be one of the bad people that ‘would never be allowed fanshen’ 永不得翻身, that is to be rehabilitated. But, by then I had learned that in China, more than nearly anywhere else, the word ‘never’ rarely meant ‘never’. It must have been at some point in 1978 and I spotted Rittenberg on the Friendship Bus that stopped in at the Foreign Languages Press at Baiwan Zhuang 百万庄, on its afternoon trip in to the Friendship Store at Jianguomenwai.

Rittenberg was still under a cloud and people spoke about him in hushed tones. In the mid 1960s, as a foreign firebrand in Maoist Peking, he had been part of the take-over of Radio Peking, the station where he had previously worked as a foreign expert. At the height of extremism, he became for a time one of the Maoist enforcers at his old work place helping bring to the foreign language service the zealotry that was metastasizing through every radio in China itself. The voices in the air that I’d heard at Samson Voron’s house in Randwick ten years earlier were broadcast by an organisation taken over by Rittenberg as part of the extremist media push by Cultural Revolution radicals. I would also learn that the prose I had come to regard as the formal style of mainland Chinese was further developed around the same time by Chen Boda 陈伯达, one of the most important ideological writers of twentieth-century China who, along with Mao Zedong’s other secretaries and ideologues, forged a prose style of colourful high dudgeon and near-comic extremism that still underpins the tenor of China’s official voice in the twenty-first century. Today, Xi Jinping’s ideological majordomo, Wang Huning 王沪宁, continues along the well-trodden path of Chen Boda.

Turn Off, Tune Out

From 1977 until the early 1990s, I often stayed at Baiwan Zhuang. Near the Beijing Exhibition Hall in the northwest of the city, Baiwan Zhuang was the location of the Foreign Language Press office-and-residential complex. Not long after my time picking apples at the People’s Commune in Jin County I had been introduced to the translators Xianyi and Gladys Yang. They befriended me and invited me to use their apartment at Baiwan Zhuang as my Beijing home during the years when I worked in Hong Kong, as well as later while living and studying in Japan. Through their kindness I learned a little of the workings of China’s international propaganda effort in the early post-Cultural Revolution years, and it was because of my time at the Foreign Languages Press when I occasionally took the ‘friendship bus’ into town with Gladys on shopping expeditions, that I caught sight of Sidney Rittenberg. It was also with Gladys and Xianyi that I enjoyed a rare moment of revenge on those invasive loudspeakers — so tellingly called laba 喇叭 (a word that means both loudspeaker and trumpet).

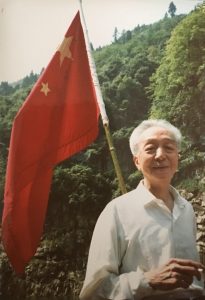

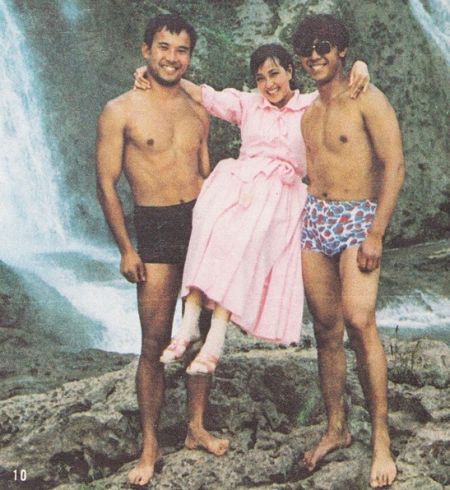

It was the early summer of 1986 and along with my soon-to-be-wife, the writer and journalist Linda Jaivin, and a friend who worked for Libération, Philippe Grangereau, I was invited by the Hunan novelist Gu Hua 古华 to join Xianyi and Gladys — the translators of his work into English — on a trip to a village in West Hunan province. Little changed since the 1970s, the town was being used as the location for the screen adaptation of Gu’s popular novel Hibiscus Town 芙蓉镇 which was set in the Cultural Revolution. (The film was directed by the veteran filmmaker Xie Jin 谢晋 and the cast included the well-know star Liu Xiaoqing 刘晓庆 and the up-and-coming actors Jiang Wen 姜文 and Liu Linian 刘利年).

Sitting in our Soft Sleeper compartment on the train from Beijing to Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan, I thought Gladys and Xianyi had probably had enough of incessant broadcasts and mind numbing lectures from the Party. They had both been jailed for four years in the late 1960s: Gladys as a foreign spy and Xianyi for being a corrupting agent of influence. Xianyi had been confined at Banbu Qiao, a Beijing prison for common criminals where, just as in the mega prison of China on the outside, life was regimented by broadcasts, study sessions and group discipline. As a high-status international agent, however, Gladys was sequestered at Qincheng, the political prison on the outskirts of the city. She was placed in solitary confinement and restricted to listening to news broadcasts and reading the official press. For Linda the blare of the loudspeaker on the train was relatively exotic, although annoying, for me it was unbearable: loud, inane and a continuation of the aural force-feeding I’d experienced for over ten years. The mind-numbing propaganda of the past, however, had been replaced by the saccharine inanity of Kong-Tai-Mainland ersatz culture. The loudspeakers on trains, as in villages and many other places, were built so they could only be turned off from a central control. Regardless, I climbed on a bunk and ‘decommissioned’ the loudspeaker with extreme prejudice. The remainder of the trip passed in the happy clamour of our own making.

In a Drop of Water

From early 1978, Beijing produced CCTV News, a thirty-minute nightly program. Feature stories generally mirrored the contents of People’s Daily and the nightly radio broadcasts, all of which were in keeping with an information policy called ‘the unified calibre’ 统一口径 by means of which the Party and the state spoke to the nation with an undivided voice.

During the tumultuous events of the spring-summer of 1989 the evening news was used to issue its admonishments, alerts, warnings and its version of what today would be called ‘fake news’. Some courageous broadcasters, inspired by the limited freedoms allowed by Party leaders like Hu Qili 胡启立, strayed into the realm of real news. For a few precious weeks in May, the Beijing media factually reported on what was happening in the streets. It was perhaps the first and last such moment that the People’s Republic has experienced in some sixty-nine years.

The broadcaster Xing Zhibin 邢质斌 had been half of the CCTV News male-female on-air team since July 1981. As female anchorwoman her voice was as famous as her matronly appearance, which included a notoriously helmet-like hairdo. Xing’s clipped and perfectly measured delivery was far from the hysterical style favoured during the Cultural Revolution, it was nonetheless stern and uncompromising. It was her cadences that had been heard reporting the details of the famous 1984 National Day Parade that celebrated Deng Xiaoping’s eightieth birthday (although the ostensible occasion was the thirty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic) and, again, it was Xing who gave voice to ‘The Centre’ all too often during the dramatic events of 1989. We used a clip of her reading a denunciation of the dissident Liu Xiaobo in the 1995 film The Gate of Heavenly Peace, for which I was the main writer and senior academic consultant. Xing Zhibin’s manner was robotic, her voice a relentless staccato, so much so that at times it felt as though it might even be audible underwater. Perhaps that’s why Xing’s work for the artist Zhang Peili remains so compelling.

Zhang’s video work, Water — Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary 水 ——《辞海》标准版, features the automaton-like Xing Zhibin. The newsreader had already featured in a triptych — an oil painting Zhang made in 1990 titled Water: Standard Pronunciation in 1989. In the triple frame of that work the newsreader is shown reciting a text, her authoritative ‘onscreen’ persona frozen in the frame; but for once she is voiceless. It was a striking representation of Party doublespeak: an authoritative image voided of substance.

The 1991 video, which was included in the exhibition Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World at the Guggenheim Museum from October 2017, was a coincidental creation. Zhang was editing another video work at CCTV’s New Media Center when he was able to hire Xing to read the definitions for the word 水, ‘water’, as published in the authoritative Cihai (‘Sea of Words’) dictionary. There she is at her news desk wearing a yellow blazer and black turtleneck sitting with a dark blue backdrop. She speaks into what looks like an outsized microphone on a stand, hair coiffed in the familiar carapace, her face masked in pancake makeup. Xing drones through the dictionary entry with unfailing timing and enunciation unaware that she is creating an artwork that recalls both the official version of 4 June 1989 and the terror that lurks behind Communist Party parole. Zhang Peili’s work straddles the then-evolving Chinese world that was nestled between mass politics and mass consumerism. At the time, in the early 1990s, it seemed as though that was an ‘inflection point’, a transitional on the way to some other, unknown social state. Now, decades, later, we appreciate that the video captures what has become a long-lasting reality: totalitarianism melded with commercialisation. For me, it is a world that brings to mind a line from Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas:

The Circus-Circus is what the whole hep world would be doing Saturday night if the Nazis had won the war. This is the sixth Reich.

***

Watching Water — Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary 水——《辞海》标准版 and listening to the robotic Xing Zhibin, I am reminded of a quieter yet more powerful voice, one that was also famous in 1989. It is that of the my old friend Yang Xianyi, who had invited Linda and me to Hunan in 1986. As the journalist John Gittings noted in the obituary he wrote for Xianyi in The Guardian in late 2009:

In 1987 the party old guard hit back, sacking the reform-minded leader Hu Yaobang, and paving the way for the bloody events around Tiananmen Square two years later. When the crisis came, Yang decided he could no longer shrug politics aside. ‘I could at least speak through the foreign TV and newspaper correspondents to the people outside China and tell them the true situation,’ he recalled in his autobiography White Tiger (2000).

His message was that what had happened was ‘a fascist coup engineered by a few diehards against political reform’. In a BBC interview after the massacre during the night of 3-4 June, Yang declared that the party leaders were even worse than past Chinese warlords or Japanese invaders. The authorities, probably deterred by Yang’s age and reputation abroad, left him at liberty, and after a vain attempt to persuade him to recant they merely expelled him from the party.

Xing Zhibin’s voice and demeanour resonate still in Zhang Peili’s art, a work that has outlived both its original place and time. Similarly, Yang Xianyi’s voice, although not heard on the airwaves since 4 June 1989, resounds through the timeless translations of Chinese literature that he produced with his wife and partner, Gladys. Both live on, one silent poetry woven from the Chinese world of letters, the other a poetry of measured terror that was created by an artist who uses a discordant voice reading an artless work.