The 2019 Year of the Pig, starting on the first day of the Chinese Lunar New Year which falls on the 5th of February, is cause for celebrating the inestimable qualities of the domestic pig, a creature that features prominently in Chinese history, culture, the economy and, above all, cuisine. This occasion also allows us to extend our consideration of bestial behaviours and empire, the latter being the theme of Translatio Imperii Sinici, China Heritage Annual 2019.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

5 February 2019

First Day of the

First Month of 2019

Jihai Year of the Pig

己亥豬年正月初一

***

So life begins: with mother using verse to caution us, long before we can understand her words, that the world is no place for the unwary. It is a dark message concealed in pleasant music. Deceptive packaging of this sort is a frequent characteristic of light verse, which has a fondness for dark messages. Of course, it is the sound of the thing that charms the child. As toddlers we fall under the spell of having our toes pinched to the rhythmic beat of ‘This little piggy went to market,’ but feel none of the tragedy of the piggy who got no roast beef or the one who cried all the way home.

— Russell Baker (d. 21 January 2019)

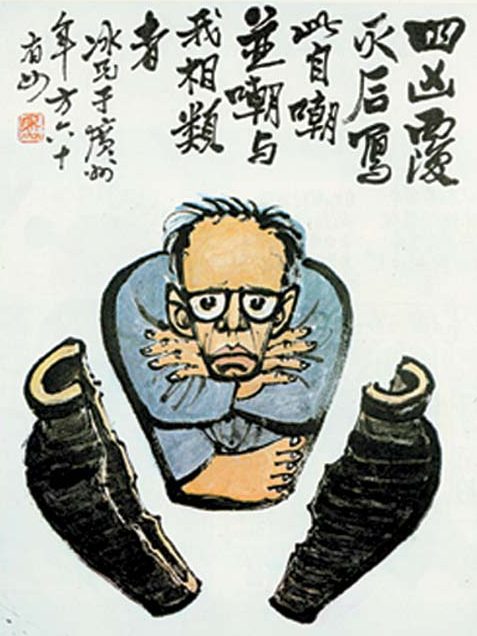

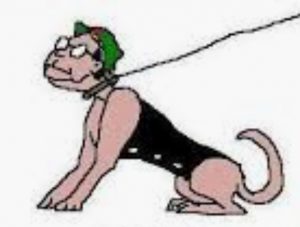

Chairman Mao’s Bitch and a Scalded Pig

First, we return to 1980, when two notorious political figures were cast in the guise of a Dog and of a Pig in popular culture.

On 29 September 1980, China’s National People’s Congress approved a decision to establish a special court to put the ‘Lin Biao, Gang of Four Anti-Party Cliques’ 林彪 、四人幫反黨集團 on trial for their activities during the Cultural Revolution era (c.1964-1978). A show trial was duly staged from 20 November 1980 to 25 January 1981 during which select moments of the proceedings were televised and reported in the official media, although the full transcript of the trial itself has not been made public.

During the show trial, Jiang Qing 江青, Mao Zedong’s widow, confronted the accusations levelled against her. She railed against those who now presumed to sit in judgment, after all, they too had been sycophantic supporters of Mao and his radical policies. She literally pointed the finger and shouted:

I was Chairman Mao’s bitch, and I bit anyone he told me to!

我是毛主席的一條狗﹐叫我咬誰就咬誰!

However, as Simon Leys pointed out at the time:

However, as Simon Leys pointed out at the time:

To ascribe to Madame Mao the main responsibility for the senseless violence and cruelty of the ‘Cultural Revolution’, for the destruction of Chinese culture, and for the ruthless cretinisation of the most sophisticated nation on earth — which have all taken place during the last ten years — would be akin to crediting the ass whose jaw Samson borrowed in battle with the ability to destroy the Philistines. The devastating effect of this unusual weapon derived from the hand which swung it: the very enormity of the havoc Madame Mao created should not allow us to forget her own essential mediocrity…

— Simon Leys, ‘Comrade Chiang Ch’ing’

Broken Images, trans. Steve Cox,

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980, p.77-78

***

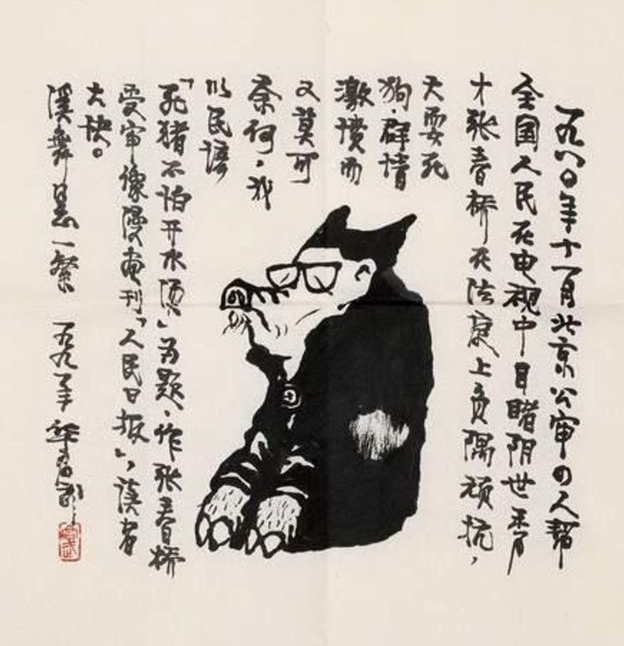

Of the other three members of the ‘Gang of Four’, Wang Hongwen 王洪文 and Yao Wenyuan 姚文元 confessed, but Zhang Chunqiao 張春橋, the theoretician and leader of the group, remained defiant and never deigned to make any statement. An ambitious Party careerist who first came to prominence in the 1950s, Zhang’s stoic silence won him a modicum of respect, even among his numerous enemies. The artist Hua Junwu (華君武, 1915-2010), famous for his satirical cartoons, was, however, unimpressed. His depiction of Zhang titled ‘Dead Pigs Don’t Feel Scalding Water’ 死豬不怕開水燙 (a common saying that means ‘beyond care and concern’) was published at the time in People’s Daily:

***

On 25 January 1981, the tribunal passed judgement on the defendants. As was (and is) customary with courts of law in the People’s Republic, all of those arraigned on charges were found guilty:

- Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao were sentenced to death, although they were granted a two-year stay of execution (Jiang committed suicide in jail in 1991 and Zhang died from cancer in 2005)

- Wang Hongwen was sentenced to life imprisonment and died in 1992 from liver cancer;

- Yao Wenyuan was handed a twenty year sentence and died in Shanghai in 2005;

- Members of the Lin Biao conspiracy were given sentences ranging from sixteen to eighteen years.

Subsequently, on 27 June 1981, a formal evaluation of the history of the People’s Republic adopted by the Party’s Central Committee named Mao Zedong as being primarily responsible for the Cultural Revolution. The document also accused the members of the now-jailed ‘Anti-Party Cliques’, led by Lin Biao and Jiang Qing, for taking advantage of Mao’s radical policies to wreak nationwide havoc and mass murder.

Jiang Qing was the last woman to serve on the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party.

***

Mao Zedong’s expression ‘Gang of Four’ gained currency in China, and is also a popular expression internationally. Just as the original ‘Wang, Zhang, Jiang, Yao Anti-Party Gang of Four’ was going on trial another, unofficial Gang of Four was purged for attempting to protect Mao’s radical legacy and its supporters. Hua Guofeng was the incumbent Chairman and a figure whose presence frustrated Deng Xiaoping’s dominance of the Party. His inner circle of advisers – Wang Dongxing, Wu De, Ji Dengkui and Chen Xilian — were found to be guilty of ‘grave errors’ and removed from the Politburo, although for a time they remained members of its Central Committee.

More recently, as Xi Jinping purged his factional enemies from 2012, there was even talk of a ‘New Gang of Four’. Bo Xilai, the ousted Chongqing Party Secretary, was lumped together with three corrupt ‘tigers’ — the former security head and Politburo member Zhou Yongkang, the Central Military Commission vice-chairman Xu Caihou and the fallen head of the Party’s General Office Ling Jihua. The four shared no factional affiliation or political program, they were merely useful foils to Xi Jinping’s rise.

Empress Lü and the Human Swine

Following the coup d’état in early October 1976, the members of the ‘Gang of Four’ were pilloried publicly. As the arrests continued a nationwide purge was orchestrated by the victorious Party leaders who, in the process, selectively released material against their fallen foes. The ‘Movement to Uncover, Denounce, Investigate [the Gang of Four]’ 揭批查運動 continued for over two years, up until the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Party Congress in December 1978. On 1 January 1979, People’s Daily published an editorial addressed to the nation which declared that the nation had successfully rid itself of the Gang of Four, their followers and their influence (see 《揭批查運動要善始善終》, 人民日報 1979年1月5日).

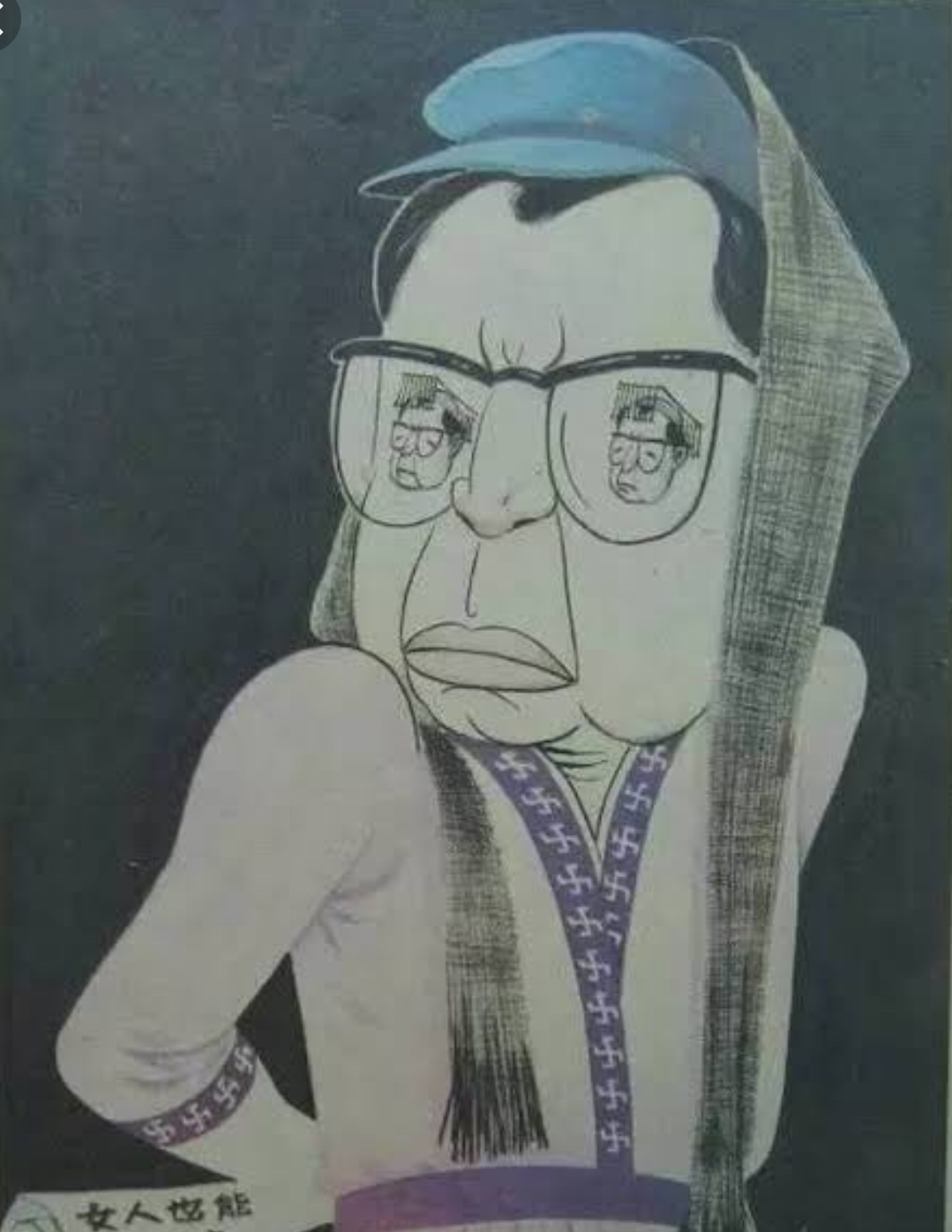

One of the more colourful aspects of the official vilification focussed on Jiang Qing as would-be empress of China. Mao’s own attendants now quoted the Chairman who had supposedly exclaimed in frustration at his wife’s constant machinations (ironic given that political plots were the lifeblood of Mao’s own rule):

Jiang Qing is wildly ambitious. The reason that she wants Wang Hongwen to be head of the National People’s Congress is that she wants to be Chairman of the Party herself.

江青有野心,她是叫王洪文作委員長,她自己作黨的主席。

Although in the more open, and directly anti-Mao atmosphere of the 1980s, the Chairman would be depicted as a latter-day emperor, in the late 1970s it was safer to attack Jiang Qing. Her detractors openly compared her to dynastic China’s three notorious female rulers: Empress Lü 呂后 of the Han dynasty; Wu Zetian 武則天 of the Tang; and the Empress Dowager Cixi 慈禧太后 of the late Qing.

For the 2019 Year of the Pig, we focus on Empress Lü of the Han. Born in what is modern-day Shandong, Lü Zhi (吕雉, 241-180 BCE) was the wife and later empress consort of Liu Bang (劉邦, 256-195 BCE), the founder of the Han dynasty, known by the title Gaozu 高祖. Following the emperor’s death, Lü Zhi was first honored as the Empress Dowager 呂太后 and subsequently as Grand Empress Dowager 太皇太后.

In the imperial biographies of Records of the Grand Historian Sima Qian devotes a chapter to Empress Lü, the only woman accorded such an honour. In it the historian chronicles the Empress’s rise to power and the fate of her Lü clan. The following extract tells the story of the first years of her imperial rule:

Empress Dowager Lü was the consort of Gaozu from the time when he was still a commoner. She bore him Emperor Hui the Filial and the queen mother, Princess Yuan of Lu. When Gaozu became king of Han he took into his service Lady Qi of Dingtao, whom he loved dearly, and she bore him a son, Liu Ruyi, king of Zhao, posthumously known as Yin, the ‘Melancholy King’.

呂太后者,高祖微時妃也,生孝惠帝、女魯元太后。及高祖為漢王,得定陶戚姬,愛幸,生趙隱王如意。

Emperor Hui was by nature weak and soft-hearted. Gaozu, convinced that the boy was of a wholly different temperament from himself, wanted to remove him from the position of heir apparent and set up his son by Lady Qi, Ruyi, instead, ‘for Ruyi is just like me,’ he would say. Lady Qi always accompanied Gaozu on his trips east of the Pass, and day and night wept and begged that her son be set up in place of the heir apparent. Empress Lü, being well along in years, invariably stayed behind in the capital, so that she rarely saw the emperor and they became more and more estranged. Ruyi was made king of Zhao and later several times came very near to replacing the future Emperor Hui as heir apparent. But, because of the objections of the high officials and the strategy devised by Zhang Liang, the heir apparent was able to keep his position.

孝惠為人仁弱,高祖以為不類我,常欲廢太子,立戚姬子如意,如意類我。戚姬幸,常從上之關東,日夜啼泣,欲立其子代太子。呂後年長,常留守,希見上,益疏。如意立為趙王後,幾代太子者數矣,賴大臣爭之,及留侯策,太子得毋廢。

Empress Lü was a woman of very strong will. She aided Gaozu in the conquest of the empire, and many of the great ministers who were executed were the victims of her power. She had two older brothers, both of whom were generals. Her oldest brother, Lü Ze, marquis of Zhoulü, died in the service of the dynasty. His son Lü Tai was enfeoffed as marquis of Li, and his son Lü Chan as marquis of Jiao. Her other brother, Lü Shizhi, was made marquis of Jiancheng.

呂後為人剛毅,佐高祖定天下,所誅大臣多呂後力。呂後兄二人,皆為將。長兄周呂侯死事,封其子呂台為酈侯,子產為交侯;次兄呂釋之為建成侯。

In the fourth month, the day jiachen, of the twelfth year of his reign (1 June 195 BC), Emperor Gaozu passed away in the Palace of Lasting Joy and the heir apparent, Emperor Hui, succeeded to the throne. At this time Gaozu’s eight sons occupied the following positions. The oldest, Liu Fei, was king of Qi; he was an elder brother of Emperor Hui by a different mother; all the rest were younger than Emperor Hui. Lady Qi’s son Liu Ruyi was king of Zhao and Lady Bo’s son Liu Heng was king of Dai. …

高祖十二年四月甲辰,崩長樂宮,太子襲號為帝。是時高祖八子:長男肥,孝惠兄也,異母,肥為齊王;餘皆孝惠弟,戚姬子如意為趙王,薄夫人子恆為代王 …

Empress Lü bore the greatest hatred for Lady Qi and her son, the king of Zhao. She gave orders for Lady Qi to be imprisoned in the Long Halls [A designation for the women’s apartments at the back of the palace — trans. note] and summoned the king of Zhao to court. Three times envoys were sent back and forth, but the prime minister of Zhao, Zhou Chang, the marquis of Jianping, told them:

‘Emperor Gaozu entrusted the king of Zhao to my care, and he is still very young. Rumours have reached me that the empress dowager hates Lady Qi and wishes to summon her son, the king of Zhao, so that she may do away with both of them. I do not dare send the king! Moreover, he is ill and cannot obey the summons.’

呂後最怨戚夫人及其子趙王,乃令永巷囚戚夫人,而召趙王。使者三反,趙相建平侯周昌謂使者曰:高帝屬臣趙王,趙王年少。竊聞太后怨戚夫人,欲召趙王並誅之,臣不敢遣王。王且亦病,不能奉詔。

Empress Lü was furious and proceeded to send an envoy to summon Zhou Chang himself. When Zhou Chang obeyed her order and arrived in Chang’an, she dispatched someone to summon the king of Zhao once more. The king set out, but before he reached the capital, Emperor Hui, compassionate by nature and aware of his mother’s hatred for the king of Zhao, went in person to meet him at the Ba River and accompanied him back to the palace. The emperor looked out for the boy and kept him by his side, eating and sleeping with him, so that, although the empress dowager wished to kill him, she could find no opportunity.

呂後大怒,乃使人召趙相。趙相徵至長安,乃使人復召趙王。王來,未到。孝惠帝慈仁,知太后怒,自迎趙王霸上,與入宮,自挾與趙王起居飲食。太后欲殺之,不得間。

In the first year of Emperor Hui’s reign, the twelfth month, the emperor one morning rose at dawn and went out hunting, but the king of Zhao, being very young, could not get up so early. When the empress dowager heard that he was in the room alone, she sent someone to bear poison and give it to him to drink. By the time Emperor Hui returned, the king of Zhao was already dead. After this Liu You, the king of Huaiyang, was transferred to the position of king of Zhao. In the summer an edict was issued awarding Lü Dai’s father Lü Ze the posthumous title of Lingwu or ‘Outstanding Warrior Marquis’.

孝惠元年十二月,帝晨出射。趙王少,不能蚤起。太后聞其獨居,使人持冘飲之。犁明,孝惠還,趙王已死。於是乃徙淮陽王友為趙王。夏,詔賜酈侯父追謚為令武侯。

Empress Lü later cut off Lady Qi’s hands and feet, plucked out her eyes, burned her ears, gave her a potion to drink which made her dumb, and had her thrown into the privy, calling her the ‘human pig’. [Early Chinese privies consisted of two parts, an upper room for the user and a pit below in which swine were kept. Apparently Lady Qi was thrown into the lower part, hence the epithet. — trans. note] After a few days, she sent for Emperor Hui and showed him the ‘human pig’. Staring at her, he asked who the person was, and only then did he realize that it was Lady Qi. Thereupon he wept so bitterly that he grew ill and for over a year could not leave his bed. He sent a messenger to report to his mother,

‘No human being could have done such a deed as this! Since I am your son, I will never be fit to rule the empire.’

From this time on Emperor Hui gave himself up each day to drink and no longer took part in affairs of state, so that his illness grew worse.

太后遂斷戚夫人手足,去眼,煇耳,飲瘖藥,使居廁中,命曰人彘。居數日,乃召孝惠帝觀人彘。孝惠見,問,乃知其戚夫人,乃大哭,因病,歲餘不能起。使人請太后曰:此非人所為。臣為太后子,終不能治天下。孝惠以此日飲為淫樂,不聽政,故有病也。

— from Shiji II, 9: ‘The Basic Annals of Empress Lü’

Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian

Han Dynasty I, trans. Burton Watson

《史記 · 呂太后本紀》

Chinese text added

***

***

Empress Lü has been vilified throughout history for promoting the interests, and power, of her Lü clan over the founding family of the Han dynasty, the Liu family. Having recorded the details of how the Liu nobility eventually outmaneuvered, and massacred, the entrenched members of the Lü clan, Sima Qian sums up the period in extraordinarily bucolic terms:

In the reign of Emperor Hui and Empress Lü, the common people succeeded in putting behind them the sufferings of the age of the Warring States and ruler and subject alike sought rest in surcease of action. Therefore Emperor Hui sat with folded hands and unruffled garments and Empress Lü, though a woman ruling in the manner of an emperor, conducted the business of government without ever leaving her private chambers, and the world was at peace. Punishments were seldom meted out and evil-doers grew rare, while the people applied themselves to the tasks of farming, and food and clothing became abundant.

孝惠皇帝、高后之时,黎民得离战国之苦,君臣俱欲休息乎无为,故惠帝垂拱,高后女主称制,政不出房户,天下晏然。刑罚罕用,罪人是希。民务稼穑,衣食滋殖。

— from ‘The Basic Annals of Empress Lü’

《史記 · 呂太后本紀》

***

In September 1968, a thirteen-year-old high-school student by the name of Kong Zhongliang 孔忠良 came upon a small stone half buried in a causeway near his home on the outskirts of Xianyang, a city in Shaanxi province built in the area that, two thousand two hundred years earlier, had been the capital of the Han dynasty.

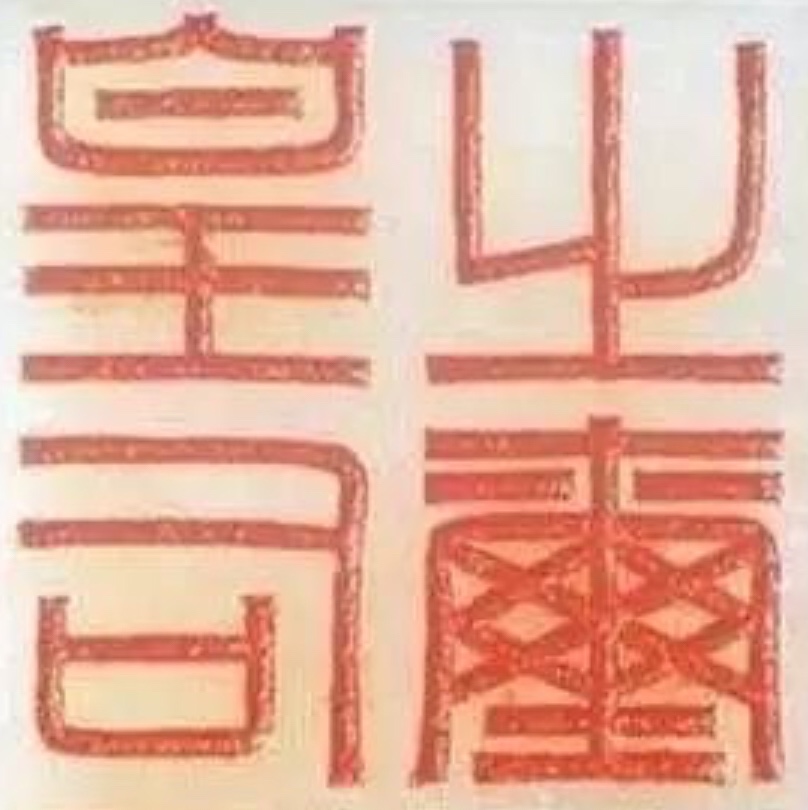

Kong’s discovery was a milk-white jade seal with the carving of a legendary hornless dragon 螭虎 on the top, and four characters on its face that read ‘Seal of the Empress Dowager’ 皇后之璽. Experts at the provincial museum determined that this was a Han-dynasty object and quite possibly the official seal of the infamous Empress Lü. In 1974, having learned of the find, Jiang Qing — a professed admirer of the Empress (she had remarked that: ‘Empress Lü was remarkable and played a significant role in Liu Bang’s career’ 呂後也了不起。她對漢高祖劉邦的事業起了很大作用) — ordered the seal be delivered to her in Beijing. It remained in her possession until her denouement in October 1976.

Eventually, the Shaanxi Provincial Museum created a purpose-built display for Empress Lü’s Seal at the Great Goose Pagoda in Xi’an. It went on display there in June 1991.

Source:

- 這枚皇后之璽, 皇后卻一天也沒用過, 18 September 2017

***

In Comrade Chiang Ch’ing, a book published in 1977 on the basis of a series of extended conversations that Jiang Qing had with the American writer Roxanne Witke, Jiang observed:

Handling cultural treasures is always fraught with perils. Some Chinese archaeologists and their students who were allowed to work at liberty with these ancient objects have grown to identify with them too closely, and consequently their revolutionary ardour has slackened . … Not all archaeological sites and relics should be preserved, since the remains of earlier historical eras are easily exploited by ambitious men.

— Simon Leys, ‘Comrade Chiang Ch’ing’

Broken Images, p.79

During the 1976-1978 official attacks on the Gang of Four, denunciations of Jiang Qing’s numerous crimes included the details of how she ‘borrowed’ 借調 artifacts and national treasures for her private collection (something of a commonplace among Communist Party leaders, both past and present). For more on this, see Yang Yinlü 楊銀祿, one-time secretary to Jiang Qing and a retried member of the Party’s Central Committee Office, 親歷1977年秦城監獄,數數江青犯下的六宗大罪, 人民網, 2010年10月29日. It is noteworthy that the Chinese version of Witke’s book published in Hong Kong was titled Empress of the Red Capital 紅都女皇.

Human Swine 人彘 rén zhì

and Xi Jinping’s Animal Farm

The broken pot that Liao Bingxiong depicted in 1976 was gradually put together again and, ever since the 4 June 1989 Beijing Massacre, cultural policing, censorship and intellectual repression have been prominent features of life in the People’s Republic. Since the Olympic Year of 2008, and in particular following the rise of the Xi Jinping autarky, not only are practices familiar from the Gang of Four era increasingly commonplace, the language used to describe — and denounce — them is familiar once more.

Given that what was once old is now new again and our interests in New Sinology, readers of China Heritage would do well to familiarise themselves with some of those older terms:

- 莫談國事 mò tán guó shì: ‘No Political Discussions!’, a slogan written on strips of paper that were posted on the walls of the fictitious Yutai Teahouse 裕泰茶館, the setting for a three-act play by Lao She revived shortly after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The action of the play Teahouse 茶館 unfolds over the years from the failed Hundred Days Reform of 1898 through the Republic of China up until the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. As the political situation becomes more unsettled, and limitations on free speech increase, the strips of paper on the walls of the teahouse warning ‘No Political Discussions!’ proliferate. Online commentators observe that a similar warning now festoons both Chinese reality and its virtual reality

- 愚民政策 yú mín zhèngcè: a ‘policy of stupefaction’. This term was widely used to describe Mao-era policies that not only ‘dumbed down’ the population but that were purposefully aimed at cretinising China. By restricting what people could learn and read, by banning all sources of independent information, the Maoist state increasingly reduced the nation to intellectual poverty. Xi-era policies have a similar intent and despite prodigious expenditures of time and labour, they remain frustrated by a flourishing publishing industry, electronic media and the Internet

- 禁 jìn: ‘to ban’, ‘imprison’, ‘restriction’, ‘taboo’. This term features in basic expressions depicting censorship like 禁錮 jìngù, ‘ban’, ‘confine’ and 思想禁錮 sīxiǎng jìngù, ‘the imprisoned mind’. The term 禁區 jìnqū — ‘forbidden zones’, or areas that are ‘off-limits’ — is used in regard to unacceptable ideas, unacceptable outspokenness, outlawed scholarship, reading and publishing

- 扼殺 è shā: ‘to strangle’ or ‘restrict’, as in 扼殺思想 è shā sīxiǎng, ‘to strangle independent thought’

- 鉗制 qiánzhì: literally to ‘seal mouths and control’, that is ‘to muzzle’, ‘silence’ or restrict, as in 鉗制言論 qiánzhì yánlùn, ‘to limit speech’

The expression ‘human swine’ — 人彘 rén zhì — along with the gruesome story related to it, has been in currency in China for over two millennia. Cartoon books, stories, films and TV shows have also told the story (with considerable relish, one would note) of the ambitious and vicious Empress Lü. The Grand Historian Sima Qian’s description of how Empress Lü turned her rival Lady Qi into a Human Swine is justly infamous:

Empress Lü later cut off Lady Qi’s hands and feet, plucked out her eyes, burned her ears, gave her a potion to drink which made her dumb, and had her thrown into the privy, calling her the ‘human pig’.

太后遂斷戚夫人手足,去眼,煇耳,飲瘖藥,使居廁中,命曰人彘。

In the 2019 Year of the Pig, the Chinese government’s modern-day formula for a new era of national stupefaction 愚民政策, although less literal, is nonetheless draconian, and relatively effective:

- Control what they can see;

- Restrict what they can hear;

- Prevent them from speaking;

- Immobilise them;

- Restrict all of their freedoms; and then,

- Display victims as a warning to others.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm has been available in the People’s Republic of China for decades. Rather than employing metaphors that refer to treacherous behaviour of Napoleon and his fellow pigs, however, in China today perhaps the temper of the times is better reflected in the breeding of new generations of ‘Human Swine’.

Forty Years Ago,

How Many Years Hence?

In 1979, China began to recover fitfully not only from the Cultural Revolution era, but from the three decades of Communist Party rule (something discussed at length by Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 in Humble Recognition, Boundless Possibility, China Heritage, 31 January 2019). Hundreds of thousands of the country’s writers, artist, as well as members of the intelligentsia who had been under a cloud for long years, found ways both to express their dread of the past and their fragile hopes for the future. The Communists celebrated the fall of the Gang of Four (as well as the demise of their ringleader, Mao Zedong) by proclaiming that this was a ‘Second Liberation’ 第二次解放. Later, independent academics would say that post-1978 China experienced a ‘New Enlightenment’ 新啟蒙, a period of intellectual exploration that mirrored the decade of open debate and cultural experimentation of the May Fourth era, from 1917 to 1927.

The 2019 Year of the Pig is a year burdened by anniversaries, some of which we too will commemorate, but it only marks the seventh year of the Xi Jinping Era. The present autarky could well last for years to come, and its repressive policies may well vie with the three decades of Maoist repression. Given Xi Jinping’s biological age (he was born in 1953), along with the longevity vouchsafed to medically pampered party-state leaders, China, and the rest of the world, may well have to wait a very long time for the next ‘Liberation’.

***

In 1976, not long after the arrest of Jiang Qing, the cartoonist Liao Bingxiong 廖冰兄 made a painting showing his crippled body newly released from a large earthenware pot. Popular belief holds that Empress Lü confined her ‘human swine’ — Lady Qi — within just such a container: