On 28 March 2017, Jean Hawkes, née Perkins, 波金絲, passed away peacefully in Minehead, Somerset, at the age of ninety. She was the widow of the Sinologist and translator David Hawkes 霍克思, who died in July 2009.

David and Jean met in Oxford a few times during the period after the Second World War when they were both undergraduates, David at Christchurch College (reading Chinese with E.R. Hughes, having worked during the war training Japanese code-breakers at Bletchley Park), Jean at St Anne’s, reading French Literature. At the time two distinguished exiled Chinese men-of-letters, S.I. Hsiung and Wu Shih-ch’ang, and their wives, competed to hold ‘salons’ for the young Oxford intelligentsia with any sort of China connection.

S.I. Hsiung (熊式一, 1902-1991) began his career in the Peking and Shanghai theatre world in the 1920s and 30s, and subsequently became famous in England for his West End and Broadway hit ‘Lady Precious Stream’ 王寶川 (it had a thousand performances at the Little Theatre in London). He was also a friend of J.M. Barrie and George Bernard Shaw, and translated some of their work into Chinese.

Wu Shih-ch’ang (吳世昌, 1908-1986), who had been a friend of the pro-Communist literary figure Guo Moruo 郭沫若, made a name for himself as a young scholar in China in the field of Chinese poetry and epigraphy (詞, 甲骨文, etc), and was later widely respected for his work on The Story of the Stone 紅樓夢 (his first major work on the novel being published in Oxford in 1961). He clashed swords many times with his rival Stone-scholar 紅學家, Zhou Ruchang (周汝昌, 1918-2012).

Wu was famous for his legendary remark to the scholar Tang Lan 唐蘭:

當今學者稱得上博極群書者,一個梁任公,一個陳寅恪,一個你,一個我.

According to family lore, David and Jean first met in 1947 at a concert given by the pianist Solomon in Oxford Town Hall on George Washington’s Birthday, the 22nd of February. Solomon played Handel before the interval, Bach variations after. Jean and David were both keen musicians and music-lovers, and Jean was able to play almost any tune by ear on the piano. The group of friends at the Solomon concert included ‘the Hsiung boys’. S.I. Hsiung père later claimed in conversation that it was at one of their tea-parties that David and Jean first met. (The Hsiungs had rented Graham Greene’s rather grand house on Iffley Turn.) At the rival Oxford salon, Auntie Wu was well-known for her cucumber sandwiches. Wu went on to become one of David’s mentors and colleagues, before returning to China in the 1960s. He was later elevated to membership of China’s National People’s Congress.

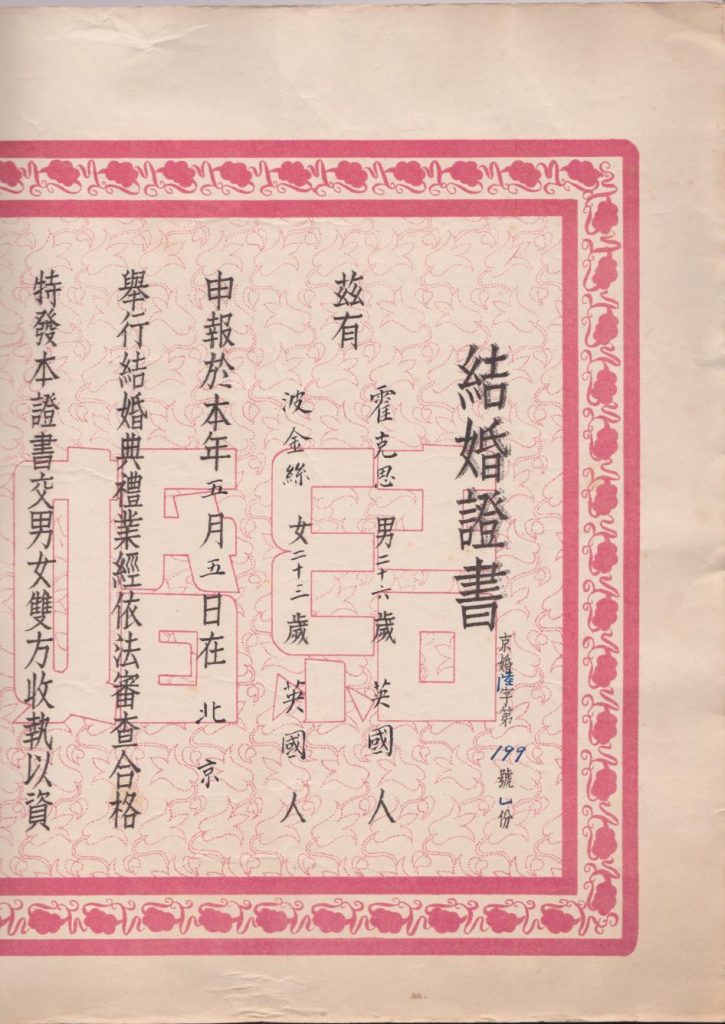

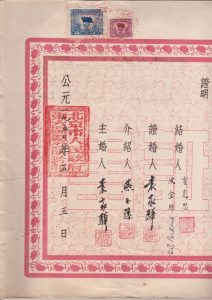

After a lengthy correspondence, David, who from 1948 was studying at Peking University, finally proposed to Jean in writing, and she travelled out by ‘slow boat’ to China in early 1950.

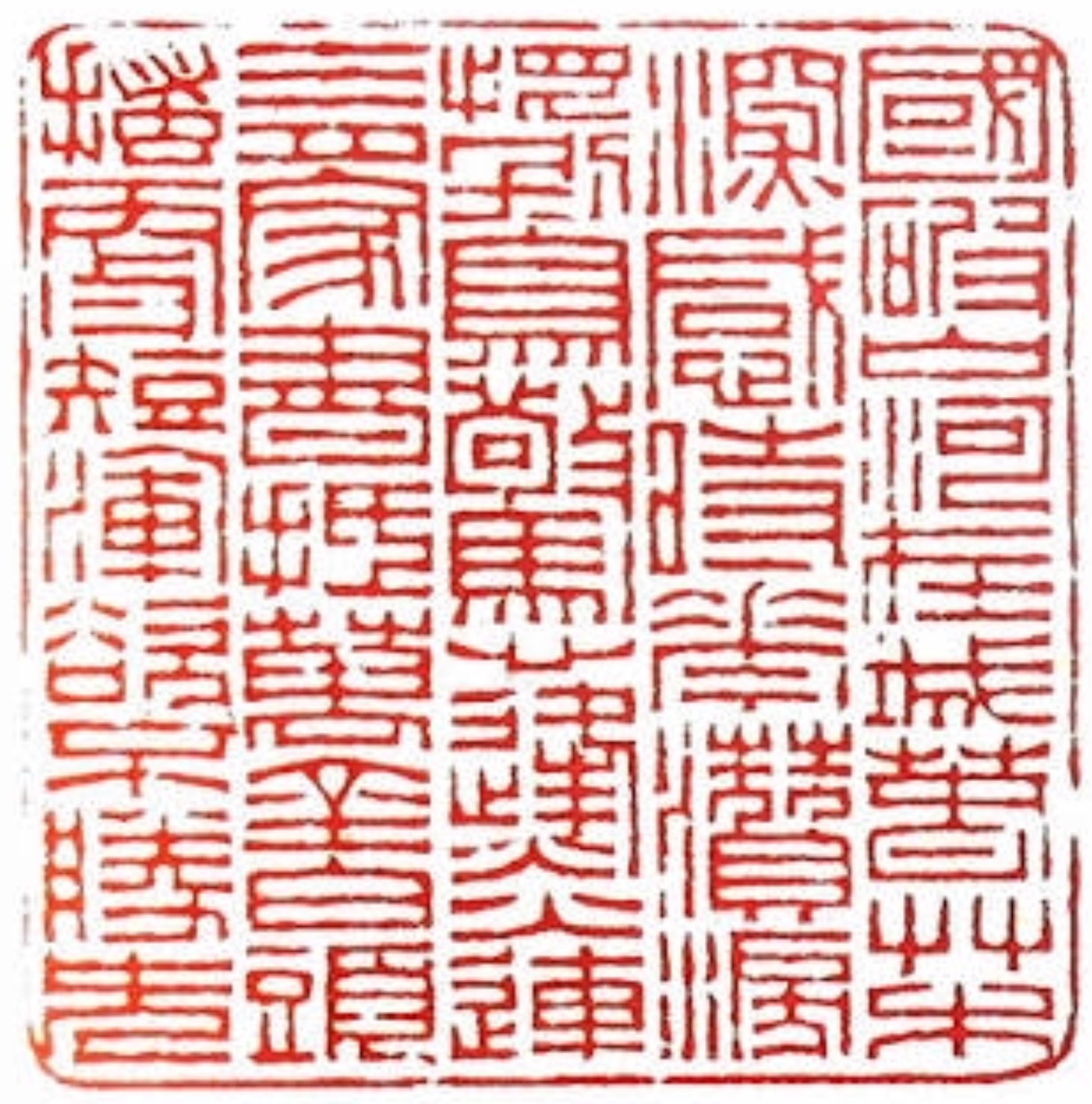

She and David were married in newly ‘liberated’ Peking. Their civil ceremony, the first foreign marriage conducted according to the new regulations for foreigners, took place on 5 May.

Afterwards they held a reception in the old British Legation, attended by (among others) William and Hetta Empson, I.A. Richards, Adele Rickett, Pamela Fitt (later Lady Pamela Youde), Robert Ruhlmann and Bishop Thomas Scott of North China.

A fine translator herself from the French, in the 1980s Jean published two translations with Virago Press of the early French feminist writer Flora Tristan:

- The London Journal of Flora Tristan, translated, annotated and introduced by Jean Hawkes, Virago Press, London, 1982; and,

- Peregrinations of a Pariah, Flora Tristan, translated by Jean Hawkes, Virago Press, London, 1985.

In the years 1970-1982, while she was working on Flora Tristan and David was working on Cao Xueqin’s The Story of the Stone, Jean was always by his side, with support, but also with bright suggestions of her own. One day, at 59 Bedford Street, Oxford, as he was in his study struggling to find an English name for Jia Bao-yu’s principal maid Hua Xi-ren 花襲人, clumsily rendered by others ‘Pervading Fragrance’, or ‘Bombarding Scent’, she called out from the kitchen to ask what was the matter. He explained the problem. Jean, glancing at the jar of Nescafé in front of her, and the words ‘New Fresh Aroma’, called out ‘What about Aroma?’ And so the maid became Aroma.

I myself first met Jean in 1967 at one of the many tea-parties she hosted for David’s students. I heard the Aroma story from Jean herself in 2010 when I came across a copy of the third volume of Stone in the family home, inscribed, ‘To Dear Jean, with thanks for Aroma’.

— John Minford, Melbourne, 1 April 2017

Spring Scene

David Hawkes dedicated his A Little Primer of Tu Fu, a work on the translation and interpretation of poems by the Tang writer Du Fu (杜甫, 712-770) for English readers, to his wife, Jean Hawkes. The book first appeared through Oxford University Press half a century ago; twenty years later, John Minford arranged for an authorised reprint edition through The Chinese University Press; three decades after that, in 2016, a North American edition was produced by New York Review of Books.

A Little Primer of Tu Fu was devised ‘in order to give some idea of what Chinese poetry is really like and how it works to people who either know no Chinese at all or know only a little.’ Below we reproduce ‘Spring Scene (Chūn wàng)’, Chapter 6 in the Primer, with the kind permission of John Minford and the David Hawkes Estate. (See also In the Shade 庇蔭, China Heritage, 4 April 2017.)

— The Editor, China Heritage

***

春望

Chūn wàng

國破山河在

1. Guó pò shān-hé zài,城春草木深

2. Chéng chūn cǎo-mù shēn.感時花濺淚

3. Gan shí huā jiàn lèi,恨別鳥驚心

4. Hèn bié niǎo jīng xīn烽火連三月

5. Fēng-huǒ lián sān yuè,家書抵萬金

6. Jiā-shū dǐ wàn jīn.白頭搔更短

7. Bái tóu sāo gèng duǎn,渾欲不勝簪

8. Hún yù bù-shēng zān.

Title and Subject

Chūn means ‘spring’.

Wàng means ‘gaze at’.

Chūn wàng is ‘Spring Gazing’: i.e. ‘View in Spring’ or ‘Spring Scene’.

This poem was written in occupied Chang’an in the spring of 757, half a year after Tu Fu’s encounter with the hunted prince [see the full text of A Little Primer — Ed.]. Its occasion may well have been a walk in the deserted Serpentine Park. From contemplation of public disasters — so much in contrast with the joyful exuberance of the season — Tu Fu turns to contemplation of his personal griefs and worries.

Note the skilful way in which this poem exploits the ambivalence of it images. It is stated:

- that nature, continuing unchangingly in it annual cycle, is indifferent to human sorrows and disasters;

- that, on the contrary, nature is grieving in sympathy with the beholder at the ills which beset him.

The propositions stating this thesis and antithesis are themselves couples containing antithetical lines. It is partly this involutedness which gives Chinese poetry the extraordinary richness of texture we sometimes find in it.

Notice also the sudden shifting of mood which takes place in the poem. The sombre anguish of the first part ends, as the tragic figure of the opening lines turns into a comic old man going bald on top, on a note of playful mockery which is nevertheless infinitely pathetic.

Form

This is a formally perfect example of a pentasyllabic poem in Regulated Verse. Not only the middle couplets, but the first couplet, too, contain verbal parallelism. It is amazing that Tu Fu is able to use so immensely stylized a form in so natural a manner. The tremendous spring-like compression which is achieved by using very simple language with very complicated forms manipulated in so skilful a manner that they don’t show is characteristic of Regulated Verse at its best. Its perfection of form lends it a classical grace which unfortunately cannot be communicated in translation. This is the reason why Tu Fu, one of the great masters of this form, makes so comparatively poor a showing in foreign languages.

Exegesis

1. Guó pò shān-hé zài,

State ruined mountains-rivers survive2. Chéng chūn cǎo-mù shēn.

City spring grass-trees thick3. Gan shí huā jiàn lèi,

Moved-by times flowers sprinkle tears4. Hèn bié niǎo jīng xīn

Hating separation birds startle heart

Since this is a poem in Regulated Verse, every word and every phrase in this and the following couplet must be arranged antithetically. Notice the skill with which monotony is avoided by a change of grammatical construction. In this couplet the subjects (‘flowers’, ‘birds’) come in the third place in the line, whilst in the following couplet the compound subjects (‘beacon-fires’, ‘letter from home’) come at the beginning of the line.

5. Fēng-huǒ lián sān yuè,

Beacon-fires have-continued-for three months6. Jiā-shū dǐ wàn jīn.

Home-letter worth ten-thousand taels

In our own history beacons were generally used in order to give warning of invasion. The Chinese used them a good deal in time of emergency, however, as a routine means of maintaining contact between garrisons. For example, two garrisons established at a distance of ten miles apart would light a beacon every evening, and each would know that the other was all right if it saw the fire burning at the appointed hour. To say that the beacons have been burning for three months running is therefore only another way of say that a state of military emergency has existed throughout that time.

7. Bái tóu sāo gèng duǎn,

White hair scratch even shorter8. Hún yù bù-shēng zān.

Quite will-be unequal-to hatpin

Until their conquest by the Manchus in the seventeenth century, the Chinese, like the Japanese and Koreans and other Far Eastern peoples, dressed their hair in a top-knot on the crown of the head. Their hats, like those of our grandmothers, were anchored to their heads by large hatpins which passed through the knot of the hair.

Translation

‘Spring Scene’

The state may fall, but the hills and streams remain. It is spring in the city: grass and leaves grow thick. The flowers shed tears of grief for the troubled times, and the birds seem startled, as if with the anguish of separation. For three months continuously the beacon-fires have been burning. A letter from home would be worth a fortune. My white hair is getting so scanty from worried scratching that soon there won’t be enough to stick my hatpin in!