China Heritage was launched on 15 December 2016 at the conference ‘Political Enchantments: aesthetic practices and the Chinese state’. That conference, organised by Gloria Davies 黃樂嫣 and Christian Sorace with the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, was held at ANU House in Melbourne, Australia. Gloria and Christian invited me to present an opening address, the title of which was ‘Living with Xi Dada’s China — making choices and cutting deals’. At the end of my remarks I announced that John Minford and I had founded The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology whereupon I formally launched our website, China Heritage.

I am grateful to Gloria and Christian for their kind invitation, and to the participants in the conference for their indulgent response. My thanks also to David Sheehy of Monash Arts for recording my speech, to Callum Smith, the designer of China Heritage who attended the conference, and to Lois Conner for allowing me to use her work here.

***

On this the Seventh Day 頭七 since Liu Xiaobo’s death in custody, I have decided to publish what are essentially draft reflections on four decades of dealing with the People’s Republic of China. (See also Lee Yee 李怡, Walking Together on Hiu Po Path 在曉波徑上同行.)

For the video recording of the talk and the full, revised text, see below.

***

That occasion was the first time that I had addressed an academic audience after quitting institutional academe in November 2015. My final address at (and to) the Australian Centre on China in the World in October 2015 was titled New Sinology in the Xi Jinping Era. ‘Living with Xi Dada’s China’ is the latest in our Wairarapa Talks.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

20 July 2017

Further Reading

- Telling Chinese Stories

- The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China

- A View on Ai Weiwei’s Exit

- Shared Values, a Sino-Australian Conundrum

- Seventy Years on and Australia’s Unfinished Twentieth Century

- Welcome, Comrade Ambassador

- See The Gate of Heavenly Peace for three excerpts from an interview with Liu Xiaobo

- Australia’s Shameful Silence on Liu Xiaobo

Living with Xi Dada’s China

Making Choices and Cutting Deals

Living with Xi Dada’s China

Making Choices and Cutting Deals

Geremie R. Barmé

A keynote address presented at the conference

Political Enchantments:

Aesthetic practices and the Chinese state

15 December 2016

Published on 20 July 2017

***

If a man should sleep to a time when time is no more, then his shadow may come and bid him farewell, saying: 人睡到不知道時候的時候,就會有影來告別,說出那些話——

There is something about Heaven that displeases me; I do not wish to go there. There is something about Hell that displeases me; I do not wish to go there. And there is something about your future Golden Age that displeases me too; I do not wish to go their either. 有我所不樂意的在天堂里,我不願去;有我所不樂意的在地獄里,我不願去;有我所不樂意的在你們將來的黃金世界里,我不願去。

What displeases me is you. 然而你就是我所不樂意的。

Friend, I do not wish to go with you. I will not stay. 朋友,我不想跟隨你了,我不願住。

I will not. 我不願意!

Alas! Alas! Let me drift in the land of nothingness. 嗚乎嗚乎,我不願意,我不如徬徨於無地。

— Lu Xun, ‘The Shadow’s Farewell’ 影的告別,

from Geremie Barmé and John Minford, eds,

Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience,

Hong Kong, 1986, pp.322-323.

***

John Minford and I used ‘The Shadow’s Farewell’ as the conclusion or envoi to the first edition of Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, our 1986 survey of the alternative cultural world of mainland China and the ‘Chinese Commonwealth’. Thirty years later, and eighty years after Lu Xun’s death, ‘The Shadow’s Farewell’ seems like a good place to start my talk today.

Climacterics

In 1971, fifteen years before John and I edited Seeds of Fire, I was completing my studies at Randwick Boy’s High in Sydney. A group of us were invited to be part of an ABC TV panel discussion titled ‘Leave Something for Us’. The focus of the programme was on what young people — I was seventeen — thought about the world we would inherit from our parents and grandparents. We discussed war, social inequalities, cultural change and, above all, the looming threat of environmental catastrophe. At the time, I didn’t know such expressions as ‘Global Warming’ or ‘Greenhouse Effect’, and it would be eight years before the ancient Greek earth goddess Gaia made an appearance. But, as we lived on the driest continent on the planet, we were all aware of the importance of water and the caprice of the treacherous seasons. We knew then, too, that the global weather system would transform the way we all thought about life and how we ourselves would live.

‘Leave Something for Us’ was about heritage and the future. Over the intervening forty five years I suppose I haven’t really moved very far from those high-school concerns.

Moving to Canberra the following year, in 1972, to study Sanskrit, Indian history and thought as well as Chinese and Chinese literature, I soon learned that the climate, changing seasons, the birth, growth and flourishing of plants and crops, as well as the unpredictability of the weather, were an integral part of the literary and metaphorical landscapes of the ancient agrarian cultures both of India and of China. As a student in China from 1974, I also realised how deeply ingrained in everyday life is the language of seasonal change. Our modest student stints in people’s communes definitely disrupting the planting and harvesting season of hard-working farmers, but they also involved us in the annual cycle of growth, bounty and decay.

Modern Chinese politics too was encoded in weather metaphors and, from the late 1970s, as a frequent traveller to Beijing from Hong Kong where I was working, the climate invariably featured in pre-trip preparations, and not just in regard to what clothing was to be packed to travel north. The Gang of Four had been detained in October 1976 and the unravelling of many policies of the High Maoist era, inaugurated following the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956, would unfold over the following decade. In those days, communication with China was mostly via mail and, before setting off north (at first only by train, but later by plane, then there were direct flights!), friends would alert you to what you could expect in the Chinese capital by making vague references to the weather. The political climate was unstable, as it would be throughout much of the 1980s, and epistolary pleasantries were usually couched in language about stormy weather, cloudy skies, rising temperatures, troughs and high-pressure systems. People would speak darkly of their fluctuating fortunes, using such terms as 昏天黑地;冷暖無常;黃沙蔽日;狂風大作;秋風蕭瑟;三九嚴寒;煙雨濛濛;陰雨連綿;風雪交加;風沙走石。

天有不測風雲: the vicissitudes of the climate are unpredictable. To this day, Chinese leaders use climate metaphors when discussing the uncertain global environment, once only political, now also more practically and unavoidably about worldwide climate change itself.

‘In China the future is fixed, only the past changes’, as one wag put it. Despite the talk of weather and the warming of the planet, in Xi Jinping’s China the future has been determined and formulated in the Party’s strategic goals of achieving the 2021 and 2049 Dual Centennials 兩個一百年; the statistician’s ledger for growth, change and development has frozen the path to the future. Despite this, there is constant climactic uncertainty and a fear of unforeseen weather conditions; the forward planning of China’s party-state is the dream of numbers-obsessed bureaucrats and economists everywhere. Yet, all these rigid plans of men can never reflect the fluid shape of humanity, and history itself has no form. People often revel in the unpredictable and uncertain; they can even thrive. For those who believe that in China they have seen the future — and that it works — I would suggest that if things do indeed go according to Beijing’s plan, then those who study, engage with and care about the Chinese world need to have contingencies of their own, and to lay them in store now.

Around this time next year, at the Nineteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping will duly be reappointed as party-state-army supremo. That means that, baring unforeseen circumstances such as accidents and illness, all of you here today will live through at least six more years of Xi Dada’s rule. Indeed, if, as I have been suggesting since late 2013, Xi breaks with recent precedent and continues beyond the customary decade of rule as Party leader, your careers in China will be darkened by his doughy shadow for many years to come. So, this laden anniversary year of 2016 may in fact be just the end of the beginning of a rule that could well see me out (I’d be over seventy if Xi goes for a third or more five-year terms and, given my precarious health, I doubt if I’ll see the back of Xi zhuxi). And it will see you into middle and, in some cases, late-middle or even early old age.

It’s a sobering thought. Climate change has happened in China; the heat is on; the air is unbreathable; sea levels have risen and there are no clear skies ahead.

Promised Dawns

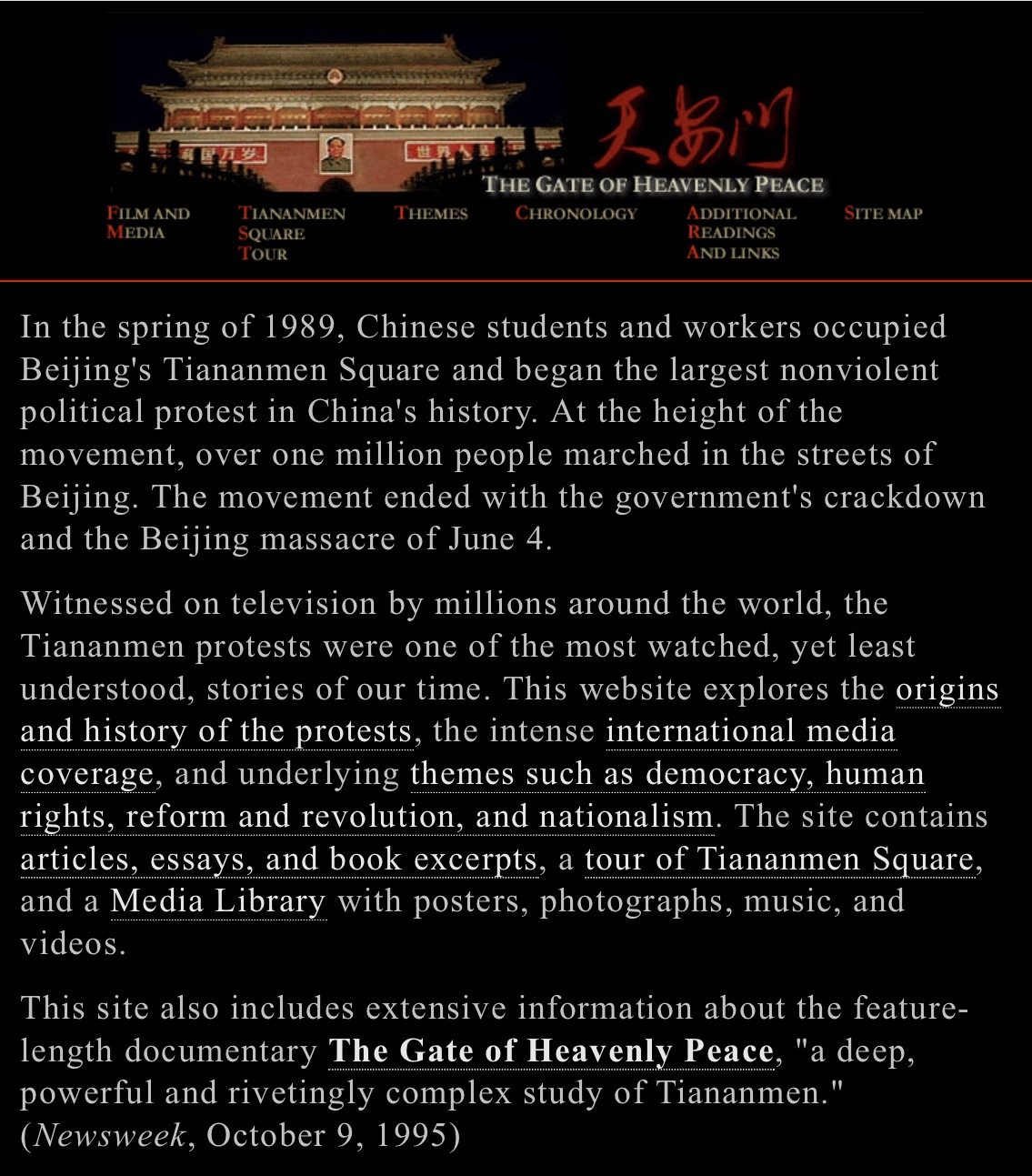

It’s nearly twenty years since I started work on a second major collaboration with my film maker friends at the Long Bow Group in Boston, Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon. We decided that, after our 1995 film The Gate of Heavenly Peace, we would try to make a ‘prequel’ to our account of 1989; it would be a film about the Cultural Revolution. As the project developed we devised a title that resonated both with the nationalistic as well as the socialist messages of the Cultural Revolution. We called our film Morning Sun or, in Chinese, 八九點鐘的太陽.

The expression ‘the sun at eight or nine in the morning’ is taken from a famous speech made by Mao Zedong on the occasion of his 1957 trip to Moscow to attend celebrations of the fortieth anniversary of the founding of the world’s first socialist country. On 17 November that year, when meeting with Chinese students and trainees in the Soviet capital, Mao said:

The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigour and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you. The world belongs to you. China’s future belongs to you.

世界是你們的,也是我們的,但是歸根結底是你們的。你們青年人朝氣蓬勃,正在興旺時期,好像早晨八九點鐘的太陽。希望寄託在你們身上。

[I particularly favoured this title as it resonated with a chilling song in one of my favourite films from the early 1970s, ‘Cabaret’. I saw it with my German-Jewish grandmother, or Omi (a contraction of the word ‘Grossmutter’), Johanna Barmé, at the Metro Cinema in Kings Cross, Sydney shortly after it was released in September 1972, and before long — much to Omi’s bewilderment — I went to study in Maoist China. The song ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Me’ is a rousing Nazi anthem sung by a blond-haired and blue-eyed Nazi youth in a bucolic beer garden. It features the line: The morning will come when the world is mine.]

The message was simple: the future does indeed belong to the young, but it might not be a future that the young can foresee, or one that they necessarily all want.

This is no less true today that it was when Mao addressed Chinese students in Moscow nearly sixty years ago. After all, people of a certain age find, here in the middle of the second decade of the twenty-first century that we have lived into a vile era of reinvigorated nationalisms, racial discrimination and persecution, strong-man politics, revived ideological and religious confrontation, all added to by the stultifying effect in institutions of higher learning of the industrialisation of knowledge and the blight of managerialist-directed research. It is what the political scientist Yascha Mounk has called the dawning of the age of ‘illiberal democracy’.

These experiences, and my continued meditation on China in the Xi Jinping era, suggested today’s topic and they inform these remarks.

And with Xi Jinping, the man whom I have from early on in his tenure called the ‘Chairman of Everything’ has risen in parhelic imitation (or is it unintended parody?) of the effulgent Mao himself.

Sunrise ushers in the dawn, and over the past century China has celebrated many dawns, most of them false. This year, with the avoidable rise of Donald Trump (pace Bertolt Brecht and Artuo Ui: recall that line, ‘Do not rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.’) and a new era not only in US-China relations, but in the dynamics of global politics, may well be yet another such false dawn.

With each dawn, each spring and new year has come a revolution of the seasons and a repetition, with variation, of the past. In February this year, I noted the various significant anniversaries that mark the Chinese calendar this year. They include:

- 1906: The dying days of the Manchu-Qing dynasty saw, among other things, the abolition of the keju 科舉 examination system and formal discussions by the court concerning the creation of a constitutional monarchy

- 1916: The end of the short-lived reign of the Hongxian 洪憲 Emperor, Yuan Shikai 袁世凱, who bequeathed Beijing the modern seat of government at Zhongnanhai (which he named China Palace 中華宮); the journal New Youth 新青年 launched an anti-Confucian campaign the effects of which are felt into the 1980s and beyond

- 1926: The Northern Expedition that would unify Republican China in an unsteady coalition and help pave the way for the ninety-year split between the Nationalists (Guomindang) and the Chinese Communist Party

- 1936: The death of the writer and ‘Soul of China’ 中國魂 Lu Xun 魯迅; China’s ignominious participation in the Berlin Olympic Games; the Communist Party Red Army’s Long March comes to an end; and, the Xi’an Incident 西安事變 that forced Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government to form a patriotic united resistance against the invading Japanese

- 1946: The failed reconciliation between China’s political parties and a renewed civil war which continues to this day. The short-lived flourishing of independent newspapers and journals

- 1956: The Hundred Flowers Movement when Mao Zedong and his colleagues supposedly ‘enticed snakes out of their holes’ 引蛇出洞, thereby encouraging intellectuals and others to critique the Party in the guise of reform. The resultant anti-party clamour lead to a nationwide purge of independent expression. A handful of ‘Rightists’ from this period have not been rehabilitated

- 1966: The formal inauguration of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and the uprising of the Red Guards with the support of Mao Zedong

- 1976: The death of Zhou Enlai, Zhu De and Mao Zedong; the Tangshan Earthquake; a military coup involving the detention of the Gang of Four, or the ‘Wang Zhang Jiang Yao Anti-Party Clique’ 王張江姚反黨集團 and the elevation of Hua Guofeng 华国锋 as the nominal head of a party-state junta

- 1986: The highpoint of China’s 1980s’ renaissance: attempts made to commemorate the Hundred Flowers Movement were crushed; at the end of the year students demonstrate in Shanghai and other cities in support of media freedom. This is the prelude to the fall of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang in early 1987 and the purge of liberal thinkers and activists from the Party then and again in 1989

- 1996: The first democratic election held in Taiwan for president of the Republic of China (Lee Teng-hui was inaugurated as the ninth president of the ROC, and its first democratically elected head of state)

- 2006: The inauguration of the party’s ‘Eight Do’s and Eight Dont’s’ 八榮八恥 ethics and values campaign. This built on the 1981-1983 ‘Five Stresses, Four Points of Beauty and Three Loves’ 五講四美三熱愛 civilising China movement that would in more recent times contribute to the party-state’s anti-Western ‘Core Socialist Values’ 社會主義核心價值觀 campaign

- 2016: The year that marks all of these and many other anniversaries is a time during which, although the international press carries the usual reports about The Other China, in China itself there will be muffled protests, gagged dissent, further restrictions on academic honesty, frustrated commemorations and sullen silences. All the while, the ebullient media of Official China will extol the unparalleled rule of the Chinese Communist Party under Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping.

[See 2016: The Golden Monkey 金猴, a Year to Remember, The China Story Journal, 5 February 2016; and, China’s Golden Monkey, ABC Late Night Live with Phillip Adams, 8 February 2016.]

In Australia, too, 2016 is a significant anniversary year:

- 1986 saw the introduction of the Dawkins Reforms of higher education that ushered in industrial-scale commodified education, the results of which you all live with today

- 1996 witnessed the rise of a Liberal Coalition government under John Howard which reinvigorated race-based politics; extolled the idea of Island Australia; led to a rolling back of indigenous rights; a deliberate manipulation of terror for political gains and the ushering in of the surveillance state

- 2006 saw the rise of Kevin Rudd’s Labor machine, the ouster of Howard by Kevin ’07 and, ever since, we have witnessed a decade of uncertain politics and extreme opportunism.

Seeds of Fire

For me, the first Spring of the kind that I have been describing here, started forty years ago. It was September 1976, and my class of foreign students at Liaoning University was undertaking a stint of ritualistic ‘open door schooling’ 開門辦學. We had left our cloistered college environment to pick apples on a people’s commune in Jin County 金縣, on the Liaodong Peninsula. The apples were slated for export to the ‘Soviet Revisionists’ to help generate hard income for China’s stumbling revolutionary economy.

One of us had a shortwave radio and we were able to tune in to Radio Australia. From late September that year, the official party media was full of oblique references to a power struggle in Beijing. In the second week of October, the news from Australia was clarion clear: Mao’s widow, Jiang Qing, and a group of her radical supporters, had been detained. With military flights booming overhead as we worked the apple trees and threats from our teachers not to say anything — they even locked us in our dormitories for a while — we enjoyed a privileged few days knowing what the preening cadres who generally made our lives such a misery did not: not only was Mao Zedong dead, but the Mao era itself would, like the corpse of the Great Leader himself, soon be injected with formaldehyde.

Not long after these events, the country experienced what was dubbed a ‘Beijing Spring’. It’s an expression that was used in homage to the 1956 Hungarian Uprising and the Prague Spring over a decade later. In 1976 and 1977, I travelled frequently to Beijing and saw friends at Peking University and, allowed to stay in their dormitories, would spend hours reading and copying down the Big Character Posters glued up on makeshift mat walls and corridors on the campus. They revealed the ‘crimes’ of the Gang of Four and offered leaked details from Politburo meetings as well as the activities of the Party leaders of the university, which had been a seat of Cultural Revolution activism since 1966.

In late 1978, I joined the multitudes jostling for a vantage point at the Democracy Wall at Xidan. Like them I read and wrote down notes from the Big Character Posters; their authors revealed previously jealously guarded state secrets as well as giving voice to an outpouring of pent up frustration, fury and hope. They included a poster by a young man called Wei Jingsheng. He called for China not only to pursue economic modernisation but also to be truly modern through political transformation, through democracy. Wei was soon detained, then arrested and arraigned in court on charges of counterrevolution. He was sentenced to fifteen years’ gaol. As for Democracy Wall, once it had served its purpose in the complex power struggles of court politics unfolding just down the road in Zhongnanhai, it was demolished and Big Character Posters — a form of popular protest that was also used for vicious denunciations — were banned.

Then, in March 1979, Deng Xiaoping articulated the Four Cardinal Principles 四項基本原則. These principles — which were first written into the old constitution and included in the preamble of the new, 1982 constitution — placed Party leadership and the People’s Democratic Dictatorship over all else; they underpin party rule in China to this day.

Wei Jingsheng’s detention, and the promulgation of the Four Principles, mark a key moment in the post-1976 history of one-party rule in China; those events were also a turning point in my own life. By 1979, I’d followed Chinese politics for ten years, I’d been studying and taking seriously Chinese history, politics and official discourse for five years (at the time, I was twenty-five) and I realised that, baring unforeseen circumstances, if I were to continue my Chinese life it would be one in which my own political principles and ethical norms would constantly confront the harsh realities of Communist Party rule. I was aware that if the opening stipulations of the Chinese constitution, including the Four Cardinal Principles, were not overturned, I would most likely spend the rest of my days engaged with a country and a culture dominated by a political apparatus based on a confabulated history, media distortions, the suppression of basic freedoms, state violence and an approach to humanity and human value that was fundamentally at loggerheads with what I thought were the lessons of the twentieth century.

But then I was also fortunate to have been introduced into the multiverse of Chinese culture and thought by such mentors as Pierre Ryckmans and Liu Ts’un-yan 柳存仁. Just as the Cultural Revolution ended I was lucky to have been befriended by the translators Yang Hsien-yi 楊憲益 and Gladys Yang in Beijing who, in turn, led me into the world of The Layabouts Lodge 二流堂, whose members, men and women, profoundly shaped my understanding of things Chinese. I was also fortunate to work for nearly three years with the leading Hong Kong editor and political commentator, Lee Yee 李怡, while being trained to write Chinese and appreciate Hong Kong as China’s Other by such friends as the essayist and entertainment writer Winnie Yeung (韋妮; 楊莉君) and the literary editor Pan Jijiong 潘際坰. [See My Life in Chinese.] This triangulation — the scholarship of my teachers at The Australian National University, the raucous culture of the latter-day literati of Beijing and the unique perspective of Hong Kong political commentators and essayists — allowed me to engage with what in some respects I knew full well was an ‘unchanging China’, what I’d later realise was Other China, while finding a life-path for myself that freed me to make my sense of the Chinese world, and to make meaning of a life that would be devoted to scholarship, reading, writing, translating and, when feasible, the education of others.

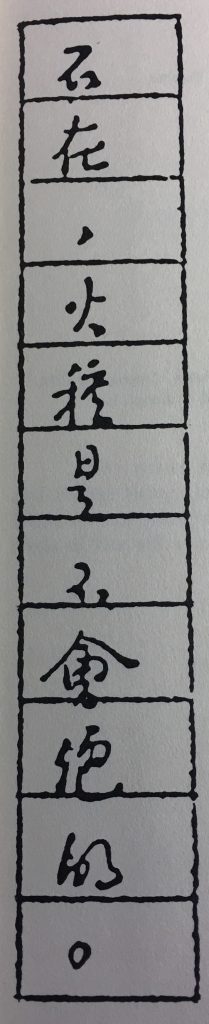

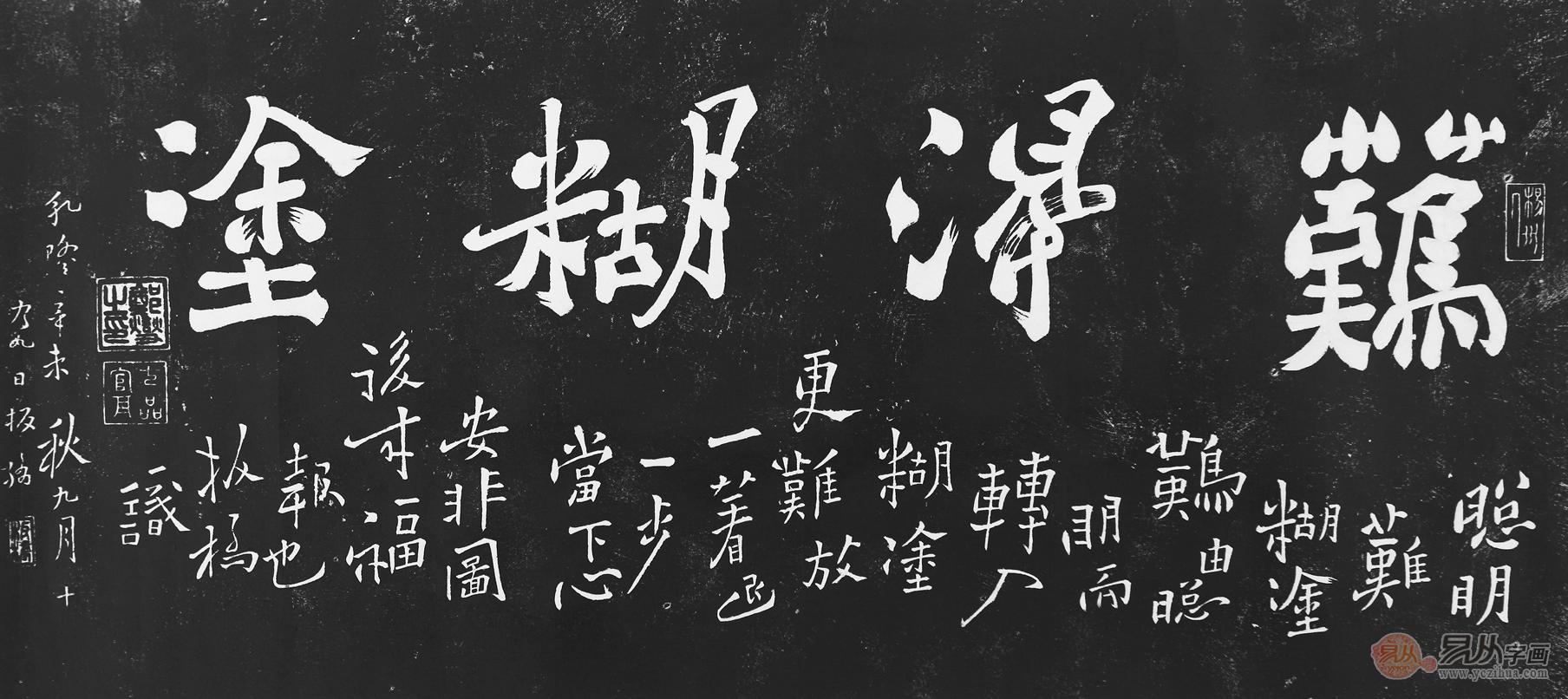

Nonetheless, in 1979 I decided to quit Chinese Studies to focus my attention on Japanese, cultural history and Buddhist Studies, a subject that had originally taken me to ANU. It was not long, however, before I was in the thrall of China once more. Despite my Japanese interests, by the late 1970s I had become a columnist writing for the Hong Kong Chinese press and I had a career outside of academia as a satirist and translator. Although the decade of the 1980s gave me scant hope that China would substantially change politically, it was a period of cultural renewal and discovery of the kind not experienced by the Chinese world since the 1930s. That’s why, when in 1986, John Minford and I translated and edited material for Seeds of Fire, we decided to dedicate our work to Lu Xun’s uncompromising spirit. The title itself, Seeds of Fire 火種, comes from a line written by Lu Xun not long before his death in 1936:

As long as there shall be stones,

the seeds of fire will not die.

石在,火種是不會絕的。

The stones are still there. Some will be used to construct new walls, both great and small. Others are seeds of fire the sparks of which promise a future, one that connects back to the alternative traditions of the past. Everyone chooses for him or herself, just what their seeds of fire may be.

Worrying China

This fiftieth anniversary year of the beginning, and the fortieth anniversary year of the denouement of the Cultural Revolution is also a year of mourning. Many men and women died in the early months of Mao’s revolution; their number includes some of the great figures of Chinese art and letters: one thinks, for example, of the philosopher Ma Yifu 馬一浮, the essayist Zhou Zuoren 周作人 (Lu Xun’s brother), the novelist Lao She 老舍, the journalist Chu Anping 儲安平. And then there is the translator Fou Lei 傅雷.

It was the early 1980s and, as I noted earlier, I had moved from Hong Kong to Japan. One of the many reasons for so doing was my trepidation about, or rather a visceral distrust of, the paternalism of China’s new era of so-called Openness and Reform. Maoist control of every aspect of society was in measured retreat and civilian life was regaining something of the lustre it had lost since the 1950s, and even since the fitful ‘renaissance’ of 1962-1964. But the dark shadow of something else was lengthening. It was evident that the rejection of the conservative Confucian code of paternalistic control, party/citizen/, teacher/pupil, father/ son pedagogy and manipulation of the young, a central element of social change throughout much of the twentieth centruy, was gradually giving way to a melded form of Chinese modernism, one in which one-party domination and moral guidance — exhortations about how to think, react to culture and to live — was evolving and being reinforced in everyday life. Youthful rebellion against this and much more would, ironically, make the 1980s the most interesting decade in China since the 1930s, but the rebellion was not only against the Party and Maoism, it was also in the direct lineage of the May Fourth rejection of sclerotic Old China (along with much of which was good about the past).

After going through all the anti-Confucianism of the 1970s (that’s the China I first encountered, one that had rightly rejected stifling state Confucianism from the 1910s), much of the old Confucian dross was reappearing: the little primers on how young girls should give in to the patriarchs, how boys should be educated and ‘listen to daddy’, how wives should be submissive and families should work. This would enter a new phase when Tu Wei-ming and his Wang Yang-ming philosophy, already adroitly taken up in Singapore, would be accepted in China and by the mid 1980s the Confucian/ Communist revival was on.

It was for these and other reasons that I gave up on Fou Lei 傅雷, the noted French literary translator whose letters to his self-exiled pianist son Fou Ts’ong 傅聰 — 傅雷家書 — had become a mini publishing sensation when they appeared in 1981. I found Fou Lei’s hardworking talent inspiring and his artistic insights compelling, but his paternalism and, eventually, his complicity not only with the Party but with the chocking tradition of Confucian patriarchal condescension in the face of difference and youthful individualism was not to my taste. In the end Fou (and his wife Zhu Meifu 朱梅馥) was a tragic figure; but he conspired in this tragedy. One notes all of the titles the party-state bestowed upon him, both in life and following his rehabilitation; one must consider therefore that he would have found in such accolades both security and satisfaction. After all, Lao She revelled in being a ‘People’s Artist’. The burden, and cost, of such accolades only became clear when both men were confronted by the Party’s Cultural Revolution, and its pitiless demands.

I had been reading Feng Zikai 豐子愷 and other writers and thinkers of the Republic for some years (since the late 1970s), and I found their mild and eclectic (and questioning) relationship with the tradition to be far more appealing: Feng is a masterful writer on the subject of ‘cultivation’ 修養, and was a wonderful artistic mentor to his own children.

Anyway, back in the 1980s, Fou Lei reminded me too much not only of how intellectuals lived under Maoism but also of just how many of them accommodated themselves relatively easily to its controlling ways; it gave them a safe haven, a place from which they could lecture others, one which allowed them to be modern, progressive, even revolutionary Chinese while also cleaving to the shreds of tradition in the belief that this was the way it could best serve their version of China. Anyway, I sensed too much of all that in the Fou Lei that I read in the early 1980s. I ended up turning away from his letters to Fou Ts’oung to Yang Jiang’s Six Records of a Cadre School Life 干校六記, my translation of which appeared in 1983 (a revised and expanded version was published in 1989 under the title Lost in the Crowd 陸沉). As for Feng Zikai, he and his work would be the subject of my doctoral research under Pierre Ryckmans and a constant companion for nearly a decade.

In a career of reading, thinking and writing one might find that you return to issues or concerns that first appeared in your teen years or twenties. I often wonder how far I have travelled from my teenage interests in the 1960s: anti-establishmentarianism, an interest in Taoism and the numinous, fascination with rebellion and concern for the thinking individual in a time of global change. I first encountered the Chinese term youhuan 憂患 in the 1980s and there’s a section in New Ghosts, Old Dreams devoted to the idea. My colleague Gloria Davies devoted a whole volume to the subject in her book Worrying About China, a profound meditation on the Chinese intellectual condition.

When I was still an undergraduate student of Chinese in Canberra, Pierre Ryckmans taught us that a study of China was profoundly enmeshed with the study and understanding of the human condition itself, so worrying about China for those of us involved personally, professionally and emotionally with the Chinese world is to worry about humanity. I summed up my own approach to these issues over a decade ago by formulating what I have called New Sinology. It is an approach that, from 2009, would inform the creation of the Australian Centre on China in the World, a research undertaking I first developed in 2007-2008 on the theme of ‘Organic China’. When writing about humanism Clive James succinctly encapsulates this approach:

Humanism wasn’t in the separate activities: humanism was the connection between them. Humanism was a particularized but unconfined concern with all the high-quality products of the creative impulse, which could be distinguished from the destructive one by its propensity to increase the variety of the created world rather than reduce it. [Cultural Amnesia, p.xix]

Worrying about China might take as its focus the People’s Republic, but it includes in its embrace the Chinese multiverse. My colleague John Minford and I started talking about this world in 1983, and that view was reflected in Trees on the Mountain, an issue of Renditions that was really the prelude to Seeds of Fire (continued with the 1992 book New Ghosts, Old Dreams), referred to earlier. In our introduction Seeds we spoke about the Chinese commonwealth, a world of Chinas that through the exchange of ideas, people, goods and political opening could no longer simply be mutually sequestered. Since then I have frequently referred to Official China and The Other China.

Worrying China is about engaging with the China of today’s regnant Xi Jinping. After all, in Xi Dada’s China, Worrying about China for the mindful scholar inevitably leads crucially to the problems associated with China Worrying About You. And you might be surprised to learn how China, and its expansive net of information gathering, does indeed worry about you. After all, you belong to the most scrutinised and self-regarding generations in history. You live under constant scrutiny: in China as well as at your home institutions. You are tracked in your fieldwork, in your research, by the university auditors and the ethics committees. By wanting to engage, make a name, develop your own voice and stance you are leaving traces, building your own heritage and accumulating legacies that will follow you throughout your lifetimes, and far beyond.

Silent China

Allow a superannuated academic like me to beg your indulgence as I reflect on the choices I have made in nearly fifty years of living with China (my interest began as a thirteen-year-old high-school student when I learned about the youth rebellion in Beijing in 1967). As I said earlier, for me 1980 was a year of some significance, and, although I launched many small jibes about the Communist state in the Hong Kong Chinese-langauge press from 1978, it was not until 1983 that I first spoke out in the English-language media about cultural repression in China. It was during the first post-Cultural Revolution political movement against Spiritual Pollution [see Spiritual Pollution Thirty Years On]. That movement passed, although during it Deng Xiaping and his ideologues such as Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun reinforced their early message about Party control over thought, politics and culture; it was a warning for the future that was generally ignored, both in China and internationally. Then there were the student demonstrations of 1986 and the purge of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang in early 1987, which John Minford and I recorded in the second edition of Seeds of Fire, published in 1988.

After that, for those who had eyes to see and ears to hear, the events of 1989 were all but a foregone conclusion. As I pursued at-arms-length academic work, I also spoke and wrote about these events, more so than ever after 1989. And then, in 1995, we released our controversial film The Gate of Heavenly Peace, for which I was the main writer and academic adviser. The film and the accompanying website garnered much praise, and not a few awards, but we also attracted the obloquy of some academics, journalists and a range of China dissidents in the US and globally. For those of you who have an interest in such things, you’ll also be aware of the long years of litigation instigated in 2007 by Tiananmen’s ‘Goddess of Democracy’ Chai Ling and endured by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon, colleagues of the Long Bow Group in Boston.

What I would observe is that deciding to take a stand and articulate your views is not a one-off act of braggadocio. In my case it has been a career-long undertaking; I look back over these forty-five years of engaging with the Chinese world, in Chinese and English, as a writer, translator, academic and film-maker without discomfort or embarrassment. Long ago, with the help of teachers in Australia, exemplars in China and Hong Kong and through reading, I learned the value of a humanism that is:

In the connection between all the outlets of the creative impulse in mankind, humanism made itself manifest, and to be concerned with understanding and maintaining that intricate linkage necessarily entailed an opposition to any political order that worked to weaken it. [Clive James, Cultural Amnesia.]

You have all worked out and will continue to negotiate your own relationship with the Chinese world. Today, I would suggest, you are all faced with the latest version of, to take an expression from Lu Xun, ‘Silent China’ 無聲的中國 (also translated as ‘Voiceless China’).

Clamorous public debate — circumscribed and self-censored discourse even at the best of times — has been gradually corralled. That is not to say that there is a dearth of noise or verbiage in the People’s Republic, or a lack of boisterous chatter on its global web, but the Storm and Fury is increasingly limited to the stentorian messages of the party-state and its loyalists, although sometimes they sound more like a threnody that repeats itself and reverberates like the death-bed message of the emperor in Kafka’s Great Wall of China. For me, this new phase of Silent China reached something of a nadir with the closing of Consensus Net 共識網 in early October this year. It was supposedly taken offline for ‘disseminating erroneous ideas’ 傳遞錯誤思想.

The present silencing of China began in earnest around the new year of 2013, shortly after Xi Jinping’s investiture as party-state-army leader. That was when Southern Weekend was attacked for advocating ‘constitutionalism’, a code expression for limiting Communist Party power (see China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China). The silence of China’s Others has spread, and I would emphasise that the pall of The Silence has been partly enabled by the policies of the US Obama administration.

As I think about China today l’m taken back once more to 1971, the year I participated in that ABC panel discussion ‘Leave Something for Us’. That was also the year when, as part of our high school ancient history class, I first read selections from Tacitus’ Annals. That historian, who chronicled the rule of the emperors Tiberius, Claudius and Nero, famously wrote:

Solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant. They made a desert and they call it peace [See also Mary Beard.]

Or, as Lord Byron poetically recast these words in Bride of Abydos:

Mark where his carnage and his conquests cease!

He makes a solitude, and calls it — peace.

Today, with the desertification of the Xi Jinping era, all those working in the Chinese world are faced with the dilemma of how exactly they can and will cut a deal with Xi Dada, his regime and Silent China.

***

It is a quarter of a century since Zhou Lunyou 周倫佑, a poet of the ‘Not-not’ 非非 school in Sichuan, produced his manifesto ‘A Stance of Rejection’. Written in response to the cultural capitulation that followed in the wake of the 4 June 1989 Beijing massacre, Zhou’s manifesto called on his fellow writers and artists to resist the blandishments of the state. ‘In the name of history and reality,’ he wrote,

in the name of human decency, in the name of the absolute dignity and conscience of the poet, and in the name of pure art, we declare:

We will not cooperate with a phoney value system—

• Reject their magazines and payments.

• Reject their critiques and acceptance.

• Reject their publishers and their censors.

• Reject their lecterns and ‘academic’ meetings.

• Reject their ‘writers’ associations’, ‘artists’ associations’, ‘poets’ associations’, for they are all sham artistic yamen that corrupt art and repress creativity.

Perhaps such hauteur seems too much, even impractical, for the career academic today (it certainly was for Zhou, and he has gone on to enjoy a successful career as a writer and academic). Some might even feel such a stance of rejection might equally apply to global neoliberal academia. But, in the era of Xi Dada, just what position will you take? As China’s propagandists promote the One Belt One Road initiative, many former colleagues have participated in the lavish conferences and gabfests devoted to the topic, adding their academic weight to a party doctrine aimed at global influence and strategic advantage. Others have been given trophies and awards for their research work in everything from gender studies and translation to Confucianism. It is chilling to see how many former colleagues and erstwhile friends have accepted these accolades (and monetary prizes) with alacrity. [Surely, today, following the death in custody of the Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo on 14 July 2017, Zhou Lunyou’s words haunt people of conscience, even those who are enticed by the largesse of Xi Dada’s China?]

You are all involved, as I have been, in making a career out of China. What does that mean in the present circumstances and, as even many of your fellows would say, ‘going forward’? The choices you make as part of this particular, highly political form of enchantment, carry particular moral and ethical burdens. Of course, one is mindful of the blandishments of academic status, research money and superannuated salaries, position, academic authority, and a stance in regard to the ongoing Sino-international chilly war 涼戰. But in this new age of The Silent China, of an Iron Room 鐵屋 in which everyone is woke, when and how do you speak out? Or do you too embrace The Silence, and comply with its designers?

I would suggest that a stance of resistance is now more necessary than ever: resistance in regard not only the enticements of a comfortable engagement with China’s party-state, but a canny resistance too in response to the globalised academic system and its forms of knowledge production. Resistance also to phoney theory, overblown hyperbolic language, the verbiage of untruth and the strategies of careerism.

In my own case, after three and a-half decades of living with China, I finally articulated with one word the kind of deal I was prepared to cut both with China and with the academic world which I inhabited. I summed it up as being a zhengyou 諍友 when relating to China, officially or through one’s work, and as an academic in my own surrounds. The idea is simple: rejecting the black-and-white dichotomy of China’s (and for that matter the ‘West’s’) Cold War approach, zhengyou favours a grounding in liberal humanist values that defends independent thought, speech, association and scholarship, while meaningfully, and respectfully engaging with the Chinese world which, as you know, exists on a spectrum from being engaging and embracing, to one of self-regarding aloofness. The concept of zhengyou as I have articulated it over the years also rejects the narrow horizons of the Audit Culture dominant in Australian, and many other, universities, as well as the limits that neo-liberal model of bureaucratic accountability imposes on the inquiring mind.

[Note: For more on zhengyou, see Contentious Friendship — Watching China Watching (XXI), China Heritage, 29 April 2018.]

Clive James:

Learned books are published by the thousand, yet learning was never less trusted as something to be pursued for its own sake. Too often used for ill, it is now asked about its uses for good, and usually on the assumption that any good will be measured on a market, like a commodity. The idea that humanism has no immediate ascertainable use at all, and is invaluable for precisely that reason, is a hard sell in an age when the word ‘invaluable’, simply by the way it looks, is begging to be construed as ‘valueless’ even by the sophisticated. In fact, especially by them. If the humanism that makes civilization civilized is to be preserved into this new century, it will need advocates. Those advocates will need a memory, and part of that memory will need to be of an age in which they were not yet alive. [Cultural Amnesia, pp.xvii-xviii]

The concept of zhengyou underpinned the research centre that I created with the support of Kevin Rudd, then the prime minister of Australia, and its dealings with China, be it the People’s Republic, Taiwan, Hong Kong or the broader Chinese world. I have argued that principled difference and reasoned contrariness are also the basis for independent scholarship. In the increasingly riven world of Sino-Other politics, the zhengyou is hardly fashionable nor indeed do those who pursue this stance readily find a purchase in self-interested academia. Nonetheless, I still recommend it to you as an approach, even as a mental disposition. Again, to quote Clive James:

…to be born and raised in a prosperous liberal democracy not only confers the energy to see the world as it is, but the obligation to make sense of it, on behalf of all those deprived of the opportunity. [from his Cultural Amnesia, p.516.]

And as for your future, a future that I do hope belongs to you, or at least some of you… . As I said earlier, on balance it is more than likely that most of you will outlive Xi Jinping’s reign, as well as the Trump presidency, for that matter. You are engaged with a Chinese world that, despite the best efforts of the Communist Party, its propaganda organs and twisted party-state education and indoctrination, is open to you. Contact with a living, complex, contradictory China is in many ways easier than ever before; you can join in fellowship with friends, colleagues and mentors in the Chinese world. China is silent, but only superficially, and The Silence will hopefully be coterminous with the tenure of Xi Jinping.

***

Coping with Xi Dada’s China

Okay, so you just want to have a peaceful life as an aspirational member of middle class, middle of the road, safe cog-in-the-machine, mid-level academia. China just happens to be your subject or career choice, just as it might be some other place, some other discipline, some other form of cookie-cutter knowledge production. You have one of those post-colonial treat-it-as-a-field-of-research and safe-career kinds of approach. Well, that’s just fine. Best of luck and enjoy the trip. My advice, my work, my ideas, our website then are not for you. For those who might aspire to something more, I offer a preliminary list of watchwords, or cautions, relevant to those who would engage with contemporary China beyond the bounds of personal expediency:

- Surveillance: Remember even in the era before meta or mass data you would have had one or more dossiers or personnel files logged with the various relevant organisations that oversee your life in China (or for that matter, in your country of origin). These are frequently added to and updated. Moreover, colleagues and friends in China may well be required to inform on you. I recommend that you read Timothy Garton Ash’s The File for an insight into what is probably happening in your China career right now, and what you might find out about it, you, your friends and colleagues some years down the track.

- Collaborations: These can come at a cost to all participants. You have to negotiate relationships constantly. Your understanding of the give-and-take required in dealing with scholars and others in a complex political landscape will develop over time and you need to be aware of the ethics of your work, not as crudely determined by mechanistic university committees, vacuous ‘ethics clearances’ and academic invigilators, but as an engaged and thoughtful individual. China constantly confronts one with issues of values and value judgements; you also need to confront them, not only for your own sake, but crucially for the sake, and protection, of others.

- Conflict: The Cold War and Peaceful Evolution: one way or the other you are involved in a struggle that has gone on since 1917 and one that was re-articulated in the Chinese context from 1959 (although its core concerns date back to the 1942-1944 Yan’an Rectification Campaign). It was behind the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalisation Campaigns of 1983 and 1987; it was reiterated in 1989 and this nexus of ideas, the policies resulting from them, has been reinforced and refined repeatedly in recent times. To appreciate the clash of ideologies (not civilisations a such) requires more than fitfully reading mass media Party propaganda; you need to take seriously Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tse-tung Thought, and its post-Mao transmogrification. [See The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China.] It is also essential to appreciate the modern history of the mercantile West. For those in the Anglosphere, it is necessary to study the rise of the global trading system, colonialism and the long history of imperialism in China.

- Self-censorship: Always thinking about how your work will be received is not a reflex merely of the writer or academic in China. [But, do read Elephants & Anacondas in China Heritage.] ‘Impact’ and efficaciousness within a system that you might not agree with; shaping your research agenda for legitimate intellectual reasons is one thing, but a cynical research life reflects as much on your scholarship as on yourself. I’d recommend you read J.M. Coetzee’s book Giving Offence: Essays on Censorship, published in 1996. [See also An Educated Man is Not a Pot.]

- Theory: The over-reach of theory and the aesthetics of making the unpalatable digestible with a coating of self-serving intellectualising is a fruitful, career-building academic strategy, but it is also a lazy way of avoiding real world questions and moral choices.

- Banqueting. The delights and pitfalls of the Banquet of China, so tellingly described by Lu Xun awaits. [See, for example, Cauldron 鼎, China Heritage, 1 July 2017.]

***

Scholar-bureaucrats in dynastic China often found themselves working for a corrupt court or during a time of strife and contention. Rather than abandon hard-won official careers — after all they had spent long years studying and taking exams so they could become officials — they chose to submit to court rule, to tolerate the tedium of routine and to survive. Many resiled from active engagement with the politics of the day or declined to take a stand over any particular issue. Rather than retire from the world entirely 隐退 yǐn tuì, however, they took an even more passive route to survive: they became recluses at court 朝隱 cháo yǐn, hiding in full sight. This hallowed term may be relevant again in China; it may even resonate with many of you.

China Heritage in The Wairarapa

Today, I am taking advantage of this lecture to announce the launching of a new venture. John Minford and I have created The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology as a way to pursue our ideas and work outside the bounds of formal academia. Its online home is called China Heritage, and our site went live today. It is a continuation of the China Heritage Project that I founded over a decade ago, in 2005, as well as an extension of New Sinology, which formed the basis of that project, and my work on The China Story 中國的故事. [See Telling Chinese Stories.]

In the Introduction to the site and the essay On Heritage 遺 I talk about my long-term collaboration with John Minford and the genesis of our Wairarapa Academy. In many ways John is the inspiration for this particular turn in my life since he, along with other New Zealand friends, led me to relocate to the Wairarapa Valley over the Rimutaka Range northeast of Wellington.

Apart from work with a few chosen colleagues and scholars, our Academy is a virtual undertaking. China Heritage is the online home of our work and it will be complimented over the next few years by three other interconnected sites, all designed by Callum Smith. These are:

- China Heritage Annual, a New Series that revives China Heritage Quarterly, which went into abeyance in 2012 [launched in Shanghai in March 2017]; and,

- A New Sinology Reader develops the ideas I first proposed with the founding of the China Heritage Project, and which informed the creation of the Australian Centre on China in the World.

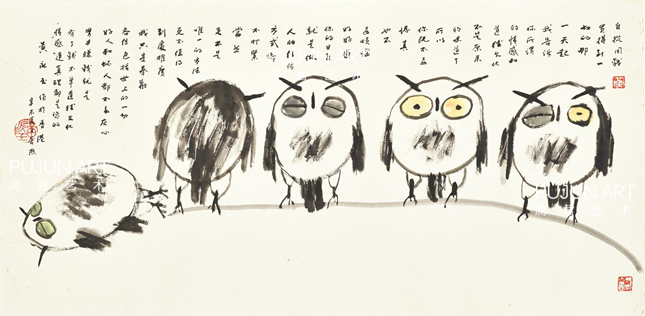

The Owl of Minerva

Over the years, I have experience three China climacterics, each a decade apart: 1979 which saw the arrest of Wei Jingsheng and the promulgation of the Communist Party’s Four Cardinal Principles; 1989 and the nationwide Chinese protest movement crushed on June Fourth; and, Christmas Day 2009, when Liu Xiaobo was sentenced on trumped up charges. Today, I have spoken in sombre tones about the present, but although I might not outlive the reign of Xi Jinping, or the pitiful careers of many of the mediocrities who crowd the stage, you, at least most of you, probably will. You should prepare now and in the years to come for that future as well, and it is to that end that I’ve addressed you as I have.

Hegel famously remarked that: ‘The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.’ That is, wisdom — the owl of the goddess Minerva — only fully takes flight or unfolds after the fact. But for us it is still daytime; it is a day that began with the morning sun of promise. Although it is too early to tell what time of day it is now, there is no doubt that it will — as do all things — draw to an end. The lengthening shadows of dusk — recalling the shade from Lu Xun with which I started this talk — will then offer a measure of wisdom and a better understanding of the world in which we are now living.

Next year [2017] marks the centenary of the start of China’s New Culture Movement, a movement that advocated mass literacy and writing. At this conference one of your guiding lights is Lu Xun, who died in 1936. In 1927, as I noted in the above, he gave a lecture in Hong Kong called ‘Silent China’ 無聲的中國. In it he spoke of the ‘fearful inheritance’ 可怕的遺產 of China: the burden of the classical written language and its limitations. He called for the use of vernacular that could truly give voice to the aspirations of the Chinese. But Lu Xun knew better than most that language itself did not determine reality — though he did not live to see the fearful miscegenation of modern Chinese with its mangled Euopean-ised syntax and vocabulary, classical affectation and the wooden parole that I have described elsewhere as New China Newspeak 新華文體. Towards the end of his talk Lu Xun said:

Youth must first transform China into a China with a voice. They must speak boldly, move forward courageously, forget all considerations of personal advantage, push aside the ancients, and express their authentic feelings. … Only an authentic voice will be able to move the Chinese and the world’s people; it is necessary to have an authentic voice so that we may live in the world with others. [trans. Theodore Huters]

The propagandists and socialist-nationalists of the People’s Republic would claim that they speak with just such a voice, and that Xi Jinping’s version of The China Story is the sole true, authentic version of China and account of the Chinese. You must determine that for yourselves, find your authentic voice and decide if and when you might ‘speak boldly, move forward courageously’.

***

I was named after Jeremiah who, it is said, was called to prophetic ministry in the year 626BCE. That makes this also an anniversary year for the man known as the ‘Weeping Prophet’. It is a year then that also marks an anniversary year for the Jeremiahs of the world. As it does the passing of one of the great poets and seers of our age, Leonard Cohen, a man steeped in Biblical and Talmudic tradition, as well as mysticism East and West. Therefore, it seems only fitting for me to end what is essentially a Jeremiad (that is, a ‘cautionary harangue’) on Cutting a Deal with Xi Dada’s China, by quoting from the Old Testament.

As chance would have it, this anniversary laden year of 2016, also marks fifty years since I first heard Pete Seeger’s song Turn Turn Turn as sung by Judy Collins. The lyrics of that song are taken nearly word-for-word from the Book of Ecclesiastes:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, a time to reap that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

— Ecclesiastes 3:1-8

Thank you for indulging me.

Further Reading

Some of the essays below also offer reflections on how to deal with my homeland of Australia: a country that has for the sake of border security, economic weal and material comfort often chosen craven silence instead of principled argument.

- Australia’s Shameful Silence on Liu Xiaobo

- Telling Chinese Stories

- The Harmonious Evolution of Information in China

- A View on Ai Weiwei’s Exit

- Shared Values, a Sino-Australian Conundrum

- Seventy Years on and Australia’s Unfinished Twentieth Century

- Welcome, Comrade Ambassador

- See The Gate of Heavenly Peace for three excerpts from an interview with Liu Xiaobo