Translatio Imperii Sinici &

a Lesson in New Sinology

‘The Dark Prince’ is Part I of ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’, Jianying Zha’s coruscating reflections on the legacy of the ancient thinker Han Fei and the Legalist school in Xi Jinping’s China. It follows on from Zha’s Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, which appeared in China Heritage on 14 July 2020.

As Zha observes, it is hardly surprising that Hanfeizi 韓非子, a decoction of the pre-Qin thinker Han Fei’s advice on rulership and political manipulation:

‘…has been compared to Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. When entering the arena of practical politics, both works check morality at the door, both excel at a pure (a priori?) and high-level exploration of the art of wielding and maintaining power. If, however, there is a contest for the title of who first formulated the ways and means to pursue totalitarian political control, I’d wager that China’s Prince Han surely comes out on top.’

As contestation between the United States and China’s People’s Republic has intensified in recent years, the old ways of instant expertise — that kind of ‘pop China literacy’ that has been modish in the business world and among Western political apparatchiki, as well as media mavens cum-influencers for decades — have taken something of a ‘Sinological turn’.

Nowadays, even figures like Newt Gingrich, the odious Republican Machiavelli, and the irrepressible guru of market democracy Francis Fukuyama — offer caricatures of Emperor Qin Shihuang and China’s autocratic tradition with aplomb. As unflappable political nabobs add new chapters to the old story about the unchanging China, Jianying Zha’s ‘Han Fei philippic’ comes as a timely corrective.

***

‘China’s Heart of Darkness’ essay is presented as a ‘Lesson in New Sinology’, one of a series focussed on the kinds of ‘literary-historical-intellectual’ 文史哲 usage and allusions that are used in contemporary politics and culture. It is also a chapter in our series Translatio Imperii Sinici which is concerned with the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which still powerfully influence the Chinese world, and will continue to do so.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

16 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Part I: The Dark Prince

Jianying Zha

Living Treachery

Han Fei lived in the final decades of an era known as the ‘Pre-Qin’ 先秦, that is, ‘before the Qin dynasty’. It consists of two successive periods: the relatively peaceful Spring and Autumn Era 春秋 from 770 to 476 BCE and the more violent Warring States period 戰國, from 475 to 221 BCE. A time of extraordinary intellectual freedom and cultural ferment, together these two periods were the golden age of Chinese thought, one during which thinkers like Confucius, Laozi 老子, Zhuangzi 莊子, Mozi 墨子 and many others flourished. The Pre-Qin firmament was lit up by so many brilliant stars and dazzling fireworks that the phenomenon is known as the ‘Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought’ 百家爭鳴, a term still used today, often with a tinge of nostalgia.

At the time, all territories of China’s Central Plains belonged, formally, to the crown of Zhou 周 (1046-221 BCE), the longest-lasting kingdom in Chinese history, which ruled through a formal, ritualised feudal system. The decentralised system, however, became strained over time, with conflicts erupting increasingly between the royal house, the various noble houses and the peripheral tribal peoples. As the Kingdom of Zhou slowly unraveled, throngs of lords and grandees declared their independence, and the divided states that resulted fell into ceaseless internecine warfare. The resulting ‘Warring States’ was an age of saber-rattling thymos, dominated by ambitious kings, spirited knights and blood-thirsty generals. Meanwhile, intellectual gurus, savvy strategists and eloquent lobbyists also thrived amidst the chaotic scene. They were often employed by battling kings and great noble families who sought their advice and service on matters of governance, diplomacy and war. The old term ‘crisis’ 危機 has been used as an orientalist trope to mean ‘danger provides opportunity’ (thought to have originated with US president John F. Kennedy and reminiscent of Churchill’s remark: ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste’). No matter the recent origin of that interpretation, the Warring States was a period rife with danger and opportunity.

By the time Han Fei appeared on the stage, warfare had whittled down the number of contending states to seven. Han was born into the weakest of the field, the State of Han 韓國. Information about his life is scarce: he was probably born around 280 BCE, and he was one of the many princes in the ruling clan. As a young nobleman he went to study under Xunzi 荀子, a great scholar who thrice served at the head of the legendary Jixia Academy 稷下學宫, located in the capital city of the State of Qi 齊國.

***

***

A prolific, Aristotle-like polymath, Xunzi is a complex figure who defies easy categorisation. He is considered a Confucian master by some, but that is disputed by others. The controversy has to do with the fact that, while still jostling with several competing schools –– Taoism, Mohism and the Logicians — the Confucian school itself was changing. Xunzi and Mencius 孟子, the two most famous Confucian scholars at the time, represented this evolving situation: like two branches on the same big tree, they stretched in quite different directions.

Mencius was the moralist and the purist. Convinced of the intrinsic goodness of human nature, he infused principles such as compassion and justice with a transcendental dimension. Moral virtue, for Mencius, was key for personal fulfillment as well as good governance; the welfare of the people was a core value. ‘To a country,’ Mencius declared, ‘the people are the most important thing. The state comes second. The ruler is the least important.’ If a ruler becomes a tyrant, the people have a right to overthrow him and choose another. Though honoured and generously subsidised by the King of Qi, Mencius lectured the king tirelessly, bluntly scolding him for his moral failings. To Mencius, the courage to ‘speak truth to power’ was of central concern; a true Confucian scholar must maintain his independent spirit and never compromise his moral integrity, even at the risk of his life.

Xunzi was far more complicated. To start with, he took a skeptical view of human nature, believing people to be naturally selfish, greedy and contentious. Hence, although moral education was necessary it was not enough. People had to be inculcated with the appropriate rites — 禮樂 and 禮儀 — and have good behavior drummed into them, but they also had to be disciplined and bad behavior had to be punished with severe penal laws and punishments — 刑法 and 刑罰. In this he was evidently influenced by a school of thought rooted in his home region, which stressed both rites and laws. Later labeled the ‘Qi Legalist School’, it boasted two renowned leaders who practiced this approach: Jiang Taigong 姜太公 the first Duke of Qi, and Guanzi 管子 the chancellor governing the economy under Duke Huan of Qi 齊桓公.

Xunzi’s attitude toward the ruler also marked a shift away from the principles of Mencius. Ministers should be capable and morally upright, he agreed, but as an embodiment of the state the quasi-divine sovereign must be accorded supreme authority. Tied to this vision was his emphasis on the unity of thought: heretics should be suppressed for the sake of social cohesion and stability.

Both of these thinkers were elitists, but they tinkered with Confucius’s original teachings in very different ways: Mencius highlighted the importance of the people’s welfare and the critical role of the scholar; Xunzi injected into his theories a heavy dose of top-down authoritarian androgens. Over the following millennia, each inspired countless followers.

If Xunzi merely opened the door to let a waft of realistic cool air into the stuffy Confucian edifice, his most famous student took a far more radical step: Han Fei decamped. It’s evident that Confucianism, a prime target for debunking and mockery in Hanfeizi, had never impressed the young Han Fei. Yet he clearly found Taoism appealing and he absorbed some of its elements into his thinking. A far more significant source of inspiration, however, was the Book of Lord Shang 商君書, the earliest surviving text of legalist thinking. A compilation of position papers, courtly petitions and ordinances, the Book of Lord Shang was a guidebook for the notoriously harsh reforms carried out in the State of Qin some seven decades before the Qin empire was founded. By the time Lord Shang (商鞅, Shang Yang), the chief architect of these reforms, met his ghastly end at the hands of his enemies, his reforms had transformed the Kingdom of Qin into a formidable militarised society. Many of Shang Yang’s grim designs for thought-control and state domination underpinned the earliest articulations of what we could call ‘a police state with Chinese characteristics’. In fact, the book deserves to be studied as a foundational text of China’s millennia-old will to the totalitarian. It also left a profound impression on Han Fei’s writing.

***

***

Two other intellectual theories, both current at the time, also appealed to Han Fei. One, developed by Master Shen Buhai 申不害, is centered on the concept of ‘tactics’ 術; the other, a formulation by Master Shen Dao 慎到, revolves around the concept of ‘propensity’ 勢. Both theories offered a rich analysis of how power was to be maintained and manipulated. The young prince fused these influences together in the process of forging his own political worldview. The result was a creative synthesis: mixing polemic argument, historical narrative and parable, Hanfeizi, Prince Han’s meisterwerk, is the most comprehensive articulation of mature Legalism. It remains unsurpassed to this day.

In Service of the Sovereign

So, what are the central tenets found in Hanfeizi? The core concern of all Confucian thinkers was benevolence and justice. This was true not only of Confucius and Mencius, but also of Xunzi, who regarded moral principles as an indispensable facet of social life and ultimately of greater worth than the orders of any particular ruler. For Han Fei, however, the nub of the problem lay with power and how it was to be exercised. Every age, he observed, has its own particular circumstances and distinct character. The Zeitgeist, he noted, was clearly force and strength.

Of crucial significance is that Han Fei’s examination of power was undertaken entirely from the perspective and in the interests of the ruler. If Xunzi had fortified the image of a paternalistic Confucian ruler as being a stern yet basically kindly or well-disposed authority, Han Fei pushed this to an extreme by melding the interests of the ruler with those of the people. For him, the sovereign was the embodiment of the state, both in terms of its power and its intelligence. In his arguments, the relationship between the ruler and the ruled is akin to that of the head and the body: the king, regularly referred to as an ‘Enlightened Master’ or the ‘All-seeing Lord’ 明主, is likened to the sober, smart head with eyes to see, ears to hear and a brain to think, whereas the people are a reactive collective of simpletons prone to infantile emotions and with thoughts befuddled by greed and base desires. That is why the head must command the body; furthermore, the amount of power and wisdom the head accrued unto itself determined the strength of the state as a whole.

With this as his starting point, Han Fei discussed power in terms of the sophisticated art of top-down control and manipulation. How could a king govern effectively from the center of the capital to the remotest corners of the land? How could he ensure that his ministers and underlings remained loyal and diligent? How best to thwart potential challengers and forestall subversive influences? How to marshal all available resources to build a strong military that could defeat all enemies?

Since the focus was no longer the issue of good or bad governance, but rather the makeup of strong and effective or weak and dilatory governance, it followed that Prince Han would want to remove entirely ethics from the equation. In struggles for power moral sentiments are of no use, indeed they too readily beclouded vision, confused judgment, or worse: they undermined authority itself. It is not surprising then that Confucian moralists were a target of Han’s ongoing mockery and verbal assaults: those elegantly-dressed, silver-tongued ‘itinerant scholars’ lobby kings and hope to befuddle the public mind with their deceptive talk of benevolence and righteousness. They have ulterior motives! To Han Fei, the moralists treated people as dupes; themselves corrupted by outside influences they were seeking nothing more than personal advantage.

The correct way to rule over a state, Han Fei argued, was by means of 法 fǎ, ‘Law’ or ‘laws’. Such a concept might sound appealing, but here we must enter a word of caution: he was not speaking about ‘the rule of law’ familiar to us from modern Western political thinking. What Han Fei was talking about was the need for an absolutist monarch to govern via a trifoliate matrix: 法 fǎ (Law/ laws), 術 shù (tactics) and 勢 shì (propensity). We cannot explicate these intricate concepts in detail here, so a few essentials must suffice:

- 法 fǎ refers to a system in which all gazetted or published laws — the penal code, promulgations relating to awards and punishments, as well as royal edicts — are designed and enforced with the aim of molding all subjects into compliant members of an orderly society. As the fundamental goal of rulership is to build a strong, unified state, harsh laws were essential to ensure absolute obedience. As for the sovereign — the ultimate umpire and final authority — he effectively remains above the law.

- 術 shù refers to a set of tactics designed for the sovereign to monitor and control his ministers and underlings. The ruler, Han Fei warns, should trust no one around him (not even his wife and children!) because they are bound to him not by affection but by ‘profit and gains’ — that is, self-interest. When it comes down to it, they are all mercantile relationships. So, how should subjects be kept in line? Han Fei offers a toolkit with a wide array of practical strategies and psychological tricks. Opacity, evasion, dissimulation, cunning, fear, secrecy, concealment, lies, surveillance, spying, traps, division, feigned ignorance, blackmail, loyalty-testing by means of provocation, cross checking of information … the list goes on.

- 勢 shì, propensity, is a notion used to describe the natural advantage afforded to one who occupies a high perch, a vantage point from which one can command, and overcome momentous forces, an unassailable strategic position that makes it possible to impose one’s will. Noting that possessing a formidable 勢 shì far outweighs mere virtue or talent, Han Fei discusses how a ruler should best protect his commanding position and exploit both its aura and its resources for maximum impact.[1]

[Note 1] See François Jullien, The Propensity of Things, in particular chapter two, ‘Position as the Determining Factor in Politics’, for a description of the Legalist concept of 勢 shì and how, in the writings of Han Fei, Shang Yang, Guanzi, Shen Dao and others, the Legalists have formulated probably the oldest political theory of totalitarianism and the surveillance state. Their design of an all-encompassing police state dwarfs and predates Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison writings by two millennia.

***

***

A Political ‘Killer App’

Reading Hanfeizi this time around, I no longer found myself bored. Instead it was a disturbing and chilling experience. I shuddered at the cynical dismissal of morality in this ancient text, the paranoid mindset of its author, his misanthropic worldview. But I was also impressed by the profound learning, the complete absence of sentimentality in Han Fei and his unsparing honesty; his ruthless yet often brilliant insights into power, political strategy and the fine art of psychological manipulation are a thing of wonder. It is hardly surprising then that Hanfeizi has been compared to Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. When entering the arena of practical politics, both works check morality at the door, both excel at a pure (a priori?) and high-level exploration of the art of wielding and maintaining power. If, however, there is a contest for the title of who first formulated the ways and means to pursue totalitarian political control, I’d wager that China’s Prince Han surely comes out on top. After all, Machiavelli’s The Prince, even with an inordinate amount of virtù stacked up on his side, must still wrestle mightily with the forces of fortuna to achieve true efficacy and glory, whereas Han Fei’s sovereign keeps himself sequestered deep within his palace and, by means of deft and subtle manipulation, allows 法 fǎ, 術 shù and 勢 shì jointly to compel compliance from all of his subjects as they work for the greater, that is his, interest. It’s easy then to see why the high-minded, righteous Confucian thinker Mencius ultimately failed in his life-long enterprise to convince any ruler to put his teachings into practice whereas, despite his ultimate grim demise, Han Fei’s ideas triumphed. Indeed, they endure in China to this day.[2]

[Note 2] There is a small trove of scholarly papers that take up the interesting task of comparing Han Fei with Machiavelli. Factors of personality and intellectual heritage aside, the pair’s resemblances and differences may be best assessed, in my opinion, as reflections of the similarly tumultuous yet ultimately quite different historical circumstances in the pre-Qin Warring States and the Florentine Republic of Renaissance Italy which informed and shaped their outlook and writing. It’s a fascinating topic the present essay cannot dwell on.

Like the Italian who fathered modern Western political philosophy by steeping himself in classical texts from ancient Greece and Rome, Han Fei fashioned his ideas on the basis of a meticulous consideration of a wide spectrum of views propounded by earlier thinkers, historical precedents, as well as in light of the rapidly changing, crisis-ridden political realities of his day.

The Central Plains of China were approaching a significant crossroad. Qin, the backward western state, having undergone a series of legal, agricultural and military reforms (thanks to the guidance of Shang Yang), was becoming more powerful and aggressive. Ying Zheng 嬴政, the ambitious Qin king, valued the advice of a courtier named Li Si 李斯, who happened to be Han Fei’s fellow student under Xunzi. Deeply worried about the condition and safety of his homeland, Han Fei repeatedly urged his own King of Han to carry out urgent reforms. The king, having surrounded himself with various glib-tongued favorites, expressed no interest in Han Fei’s ideas. Frustrated, the prince focused his thoughts — and sometimes even his heart — on writing. Aside from his no-holds-barred insights about the manipulation of power and his forceful disquisitions regarding law and order, some of the most famous essays that he composed were about the subtle art of gaining a ruler’s trust and confidence — one thinks of such works as ‘The Challenges of Convincing a Ruler’ 說難 and ‘The Frustrations of Being Ignored’ 孤憤, two of his most famous essays, which bristle with the anguish and resentment of a failed lobbyist. Circulating within the contending states like the works of so many other disaffected strategists, Han Fei’s essays eventually came to the attention of Ying Zheng in Qin. It is said that, when he read them, the King of Qin was so enthralled that he sighed:

‘If only I could meet and converse with this writer, I would die with no regrets!’

嗟乎。寡人得見此人與之游,死不恨矣。

Thereafter, the story takes a fantastic turn. To satisfy his hope of meeting Han Fei, Ying Zheng launched a war on the State of Han and, when Han sued for peace, the Qin ruler demanded that prince Han Fei be dispatched as the negotiator. Upon reaching the Qin capital Han Fei was promptly detained.

Yet again Han Fei failed, be it as an emissary of peace or as a courtly lobbyist. It would seem from his time in Qin that he had no qualms about betraying his homeland (after all, the Han ruler hadn’t appreciated his talents) nor about offering to serve the ruler of an enemy state. Only one thing betrayed his ambition: he presented badly. Han Fei stammered: he had always had an insurmountable stutter; moreover, his speech entirely lacked in grace and he was physically unimpressive. It wasn’t long before a disappointed Ying Zheng simply ignored him. Trapped in Qin nonetheless, Han Fei languished.

Meanwhile, Li Si, always keenly aware of the superior talent of his old classmate, gave in to craven jealousy. Han Fei could not possibly be allowed to leave Qin, Li remonstrated with the ruler, nor should he be allowed to live. Such a prodigiously talented man was a threat wherever he was and, as a native of the State of Han his ultimate loyalties would always lie there. Li convinced the throne to cast Han Fei into prison. All attempts by the benighted prisoner to appeal against this cruel treatment were frustrated and, by the time Ying Zheng thought better of his rash decision, Han Fei was dead, either poisoned by Li Si’s connivance or having been pressured into committing suicide. The year was 233 BCE, only twelve years before the bellicose Qin forged a unified state from the warring kingdoms of the Central Plains. Known to history as Qin Shihuang 秦始皇 — ‘First Emperor of the Qin’, Ying Zheng would declare himself the founder of the Qin dynasty.

***

***

History, however, unfolds in unpredictable ways. Also a Legalist, and the kind of political operator who knew efficacious policies when he saw them, Li Si proved particularly adept at putting Han Fei’s theories into practice. As the most influential advisor by Qin Shihuang’s side, Li proposed policies that Han Fei had painstakingly laid out. After the First Emperor died, however, political irony played out in an unsurprising way: Li soon fell prey to the jealousy of the new emperor’s favorite, a powerful eunuch by the name of Zhao Gao 趙高. Li’s fall from grace also involved the extermination of his whole clan, though Li’s own end was particularly gruesome. He now underwent the ‘Five Punishments’ 五刑 as outlined in his own playbook: first, his face was tattooed with his crimes 墨, then his nose was cut off 劓, following which both feet were amputated 刖 and he was castrated 宫. The coup de grâce came when, with one mighty blow, the executioner cut Li in half at the waist 大辟.

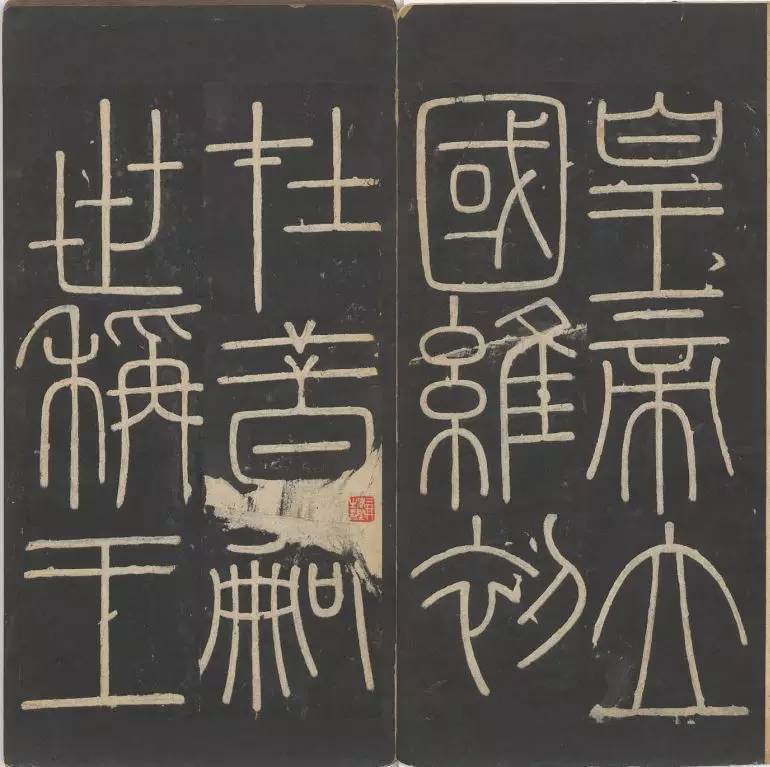

Although it was the first, the Qin was also the shortest-lived of China’s dynasties. Having achieved the unprecedented enterprise of conquering the other six contending states and establishing a united empire, the Qin lasted for only fifteen years. The First Emperor did, however, leave an extraordinary legacy, one that lives on today, over two millennia later, including a standardised written language, the centralised bureaucratic state and the first in a series of ancient defense structures known as the Great Wall. Shihuang’s reputation, however, has waxed and waned. Until the rise of Mao Zedong and the Communists in the twentieth century, the First Emperor was generally condemned for being a brutal tyrant and, even now, he is popularly remembered — and generally excoriated — for the infamy of ‘burning books and burying scholars’.[3]

[Note 3] 焚書坑儒 fén shū kēng rú. It is thought that most of the four hundred and sixty ‘scholars’ who were buried alive had been charlatans and warlocks who annoyed the superstitious First Emperor by failing to produce effective longevity pills. The books that were incinerated, banned and confiscated were mainly texts of the Confucian school.

Confucian Façade, Legalist Essence

The precipitous demise of the Qin served as a lesson for future rulers. Balancing their own oppressive rule, the early Han emperors embraced aspects of the more non-interventionist school of Taoism. Formulas that advocated ‘quiet inaction’ 清靜無為 and ‘abiding with the people’ 與民休息 would guide the relatively relaxed approach of court policies for decades, soothing the nerves of a ravaged population and would-be servants of the state who, for too long, had endured the depredations of burdensome taxation, forced labor and endless warfare.

Meanwhile, eager to participate in the new, post-Qin order, champions of Confucian ideas made a tentative comeback. It wasn’t an easy task. Liu Bang 劉邦, who founded the Han dynasty and is known as Emperor Gao 高祖, disliked Confucians and their lofty platitudes. A crude man of lowly birth, Liu expressed his scorn by literally pissing them off: he famously urinated into the headgear of a group of Confucianists when they came to pay him court. Undeterred they continued to petition the ruler and, over time, they proved their worth. As one shrewd figure put it to the emperor: Confucians might be hapless when it came to armed conflict, but they could prove useful in bolstering the empire.[4]

[Note 4] Sima Qian, the Grand Historian of the Han, records the details in his Historical Records: ‘沛公不好儒,諸客冠儒冠來者,沛公輒解其冠,溲溺其中。與人言,常大罵。’《史記 · 酈生陸賈列傳》And, ‘叔孫通說上曰:夫儒者難與進取,可與守成。’ —《史記 · 叔孫通列傳》

A critical breakthrough occurred during the reign of Emperor Wu 武帝 (r.141-87 BCE). A scholar named Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 devised a theory that combined elements from various schools of thought — the cosmology of Yin-Yang and Five Elements theory, the worship of Heaven, Taoism and Legalism — in an integrated Confucian framework of moral governance. This new doctrine of rulership included the concept of the ‘Mandate of Heaven’ 天命 tiān mìng, a Chinese version of the ‘divine right to rule’ and one in which a worthy emperor enjoyed moral and political legitimacy because they were a ‘Son of Heaven’ 天子 tiān zi, that is a superior individual who demonstrated both on and off the battlefield that they were enacting the Will of Heaven 天道 tiān dào itself.

In Dong’s schema, Heaven was like a double-edged magical sword which could bless a virtuous ruler with peace and prosperity while punishing a bad ruler with chaos and calamity. Dong also reworked certain Confucian principles and ritual behaviour to accommodate them within a monolithic and rigid hierarchical social and political order. Among other things, he devised the famous paternalistic ‘Rules of the Three Cardinal Relationships’ or 三綱 sān gāng: the sovereign rules over ministers; fathers rule over sons; and husbands rules over wives.

Dong transformed Confucianism into a practical political ideology that well served the needs of a newly consolidated imperial power: it provided a theoretical basis for the divine legitimacy of the ruler and it articulated a top-down moral structure for society. At an important court debate in 134 BCE, Emperor Wu endorsed Dong’s Confucian proposals and rejected all others as heretical. From then on the works codified as the ‘Confucian classics’ were enshrined as part of dynastic and state orthodoxy.[5] It was a watershed moment, comparable perhaps to Constantine’s decree adopting Christianity as the state religion of the Roman empire in the West. To all intents and purposes, State Confucianism was the civil religion of dynastic China until the abdication of the last Qing emperor in early 1912.

[Note 5] Chief among these state enshrined canonical works, from Han through Tang, were the ‘Five Classics’ 五經: 詩經、尚書、禮記、周易 and 春秋. Then, from the eleventh century, the ‘Four Books’ 四書 — The Analects 論語, Mencius 孟子, The Great Learning 大學 and The Middle Way 中庸 — were added.

What about Legalism? Given the prominent role it had played in the rise, and fall, of Qin, this body of thinking suffered serious reputational damage. In the eyes of many Confucian literati over the ages, especially those with a Mencian predilection, Legalism would always symbolise amoral and draconian rule. In practice, however, even from the Han era, Legalism had its canny supporters and they played a key role in ensuring that approach to statecraft never quit China’s political stage.

***

***

Indeed, from the Han, Legalist ideas related to 法 fǎ would shape dynastic legal systems — including penal codes, criminal laws, judicial structure and so on — from then on. Meanwhile, the orthodox ‘State Confucians’ gradually reached an accommodation with the Legalists and together they would pursue the common cause of what today would be called ‘stability maintenance’. Over time, a system of ‘rule by rites and laws’ 禮法治 lǐ fǎ zhì evolved. Like a two-prong instrument performing a complicated operation, the two former contenders for power and influence would work side by side to tackle the same enemy and maintain a joint vision of rulership. The once mutually exclusive governance models identified commonalities as well as overlapping responsibilities: the Confucians employed Rites to vouchsafe a socio-political hierarchy and to enable the policing of customs and cultural mores that contributed to the cohesion of the state; the Legalists deployed Laws — penal codes, law enforcement and courts — to mete out forms of justice that also echoed the values of State Confucianism. In its mature form, this kind of Confucian-Legalist model of co-governance contributed to dynastic China, whose history was in constant flux, achieving a remarkable level of self-correcting continuity.

As for 術 shù (tactics) and 勢 shì (propensity), these aspects of Legalism remained as strategies for the sole benefit of the rulers; the ruled were neither supposed to be privy to their mysteries, nor equipped to understand them. A text like Hanfeizi was the pinnacle of pre-Qin thinking about the art of top-down socio-political control. It remained a must-read classic for the denizens of the cloistered chambers of the imperial court where its insights were cherished, its warnings heeded and its tactics deployed. After all, every ruler wants to have access to an invincible ‘magical weapon’.

This reshuffling of the ideological and political cards took time, but eventually a new amalgam strategy for rulership took on a recognisable form. It is summed up succinctly in such hoary expressions as ‘[Maintain a] Confucian Façade, [while pursuing a] Legalist Essence’ 儒表法里; it is also reflected in the formula ‘[Promote] Overt Confucianism [in Tandem with] Covert Legalism’ 陽儒陰法. Such shorthand terms go to the heart of the ideological marriage at what would be an abiding core of Chinese statecraft. In the public sphere, Confucians and their moral rectitude appear to dominate. Confucianism may look and sound like it is top dog, but this house-trained canine has always been in the service of its true master; only if you squint can you make out the leash around its neck. It is a tether that is as delicate and supple as it is chokingly unforgiving. And guess who made the leash for the great master?

This ‘Confucio-Legalistic’ duumvirate of ideas has bequeathed to China a particular political heritage, one that has for much of the past two millennia been vital to success and longevity not only of mutating dynastic rule, but to the essence of what from Qin times is known as the ‘Imperial Enterprise’ 帝業 dì yè. The combination has weathered innumerable crises, dynastic collapses, challenges and renewals, yet it abides. The Confucian moralistic hierarchy that validates a Chinese version of the divine right to rule combined with Legalist social management has been a winning combination that, despite the ructions of the twentieth century has never been truly repudiated, partly since its abiding value and Realpolitik influence was never fully exposed or systemically rejected. As for Hanfeizi, few Chinese readers outside academia today give it much, if any, thought. This has nothing to do with censorship. After all, the text itself is forbidding enough: it is long, it is steeped in archaisms and its ideas are, superficially at least, esoteric. Like many classics, it is a work more readily referred to than actually read.

To the cognoscenti who do read it and appreciate its precepts, however, it has made the world of difference.

End of Part I: The Dark Prince

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020