Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance (XXV)

Despite being under a formal interdiction that bans him from writing or publishing new work, Xu Zhangrun has taken to reworking and releasing essays on a range of topics composed before the authorities of Tsinghua University launched their ‘kangaroo investigation’ into him in late March 2019.

In these works, published by H-Media 合傳媒, Xu touches on such topics as Chinese society, legal dilemmas, civil society, politics, totalitarianism and contemporary thought. Below we offer an overview of the nine essays that Professor Xu has published to date, with links to the original texts. An earlier work — ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’ ‘哪有先生不說話?!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018 — provides a preface to this material, which is ‘Banned in China’. In this series of ‘old tales retold’, Xu describes himself with characteristic mordant humour as being ‘an unemployed professor awaiting a job assignment’ 待業教授.

***

As we have previously noted in this series — ‘Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University’ (see, in particular, Anon., ‘Silence + Conformity = Complicity — reflections on university life in China today’, China Heritage, 30 March 2019) — the 30th of March 2019 marked the fortieth anniversary to the day since Deng Xiaoping announced the Four Cardinal Principles 四項基本原則 that have frustrated China’s political evolution. These ex cathedra ‘principles’ were formulated by Deng and his colleagues in consultation with the Party ideologues Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木 and Deng Liqun 鄧力群, figures whose baleful influence on that country’s political, intellectual and cultural life lasted for over fifty years.

The Four Cardinal Principles were a response to the popular protests and unregulated speeches and essays that flourished for a time on and around Democracy Wall at Xidan, west of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The ‘Beijing Spring’ served the needs of Party leaders, but it also allowed for dissent and open opposition to a one-party state that, for nigh on three decades, had visited misery on the nation. Earlier in March a young protester by the name of Wei Jingsheng 魏京生 posted an essay titled ‘What Do We Want: Democracy or Another Autocrat?’ 要民主還是要新的獨裁?, which contributed to the sense of urgency Deng and his comrades felt about shoring up their legitimacy. Wei was duly arrested, tried on nebulous charges and sentenced to fifteen years in jail. In late 1979, Democracy Wall was demolished.

In many ways, Deng’s Four Principles and Wei’s protest against autocracy have bedeviled China ever since. In the treatment of independent-minded intellectuals like Professor Xu Zhangrun, not to mention teachers, writers, publishers, media figures, rights lawyers, dissidents, religious leaders and groups, in 2019, we are reminded of those seminal moments in March 1979. As we have marked the thirtieth anniversary of the Beijing Massacre, we have recalled the fate of Wei Jingsheng in 1979 and the origins of the 1989 Protest Movement — the February to June ‘petition protests’ were sparked by a letter that the dissident astrophysicist Fang Lizhi 方勵之 addressed to Deng Xiaoping in January that year. In it he called for the government to announce a political amnesty to mark the fortieth anniversary of the founding of the Communist state, one that would see the release of Wei from gaol.

The protests of 1978-1979, as well as those of late 1986 and during the first half of 1989 — along with the stifled attempts by people from all walks of life to speak out against persistent autocratic Chinese traditions renewed by a modern totalitarian ideology — have, in many respects, reflected an ongoing widespread desire for normalcy, a constantly renewed aspiration for an untrammelled world, for lasting peace and quiet after the tumult and suffering of the past, as well as in the face of the ever-looming threats of the future. Perhaps again today that mood of multifaceted protest can best be understood as a universal impulse and not merely as one limited to the concerns of China’s men and women of conscience.

***

My thanks to John Minford for reminding me of the greeting card made by Pierre Ryckmans (see below) and to Richard Rigby for providing a reproduction of the card from his personal archive.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

4 June 2019

Further Reading:

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’ ‘哪有先生不說話?!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018

- Feng Chongyi 馮崇義, ‘A Scholar’s Virtus & the Hubris of the Dragon’, China Heritage, 22 May 2019

- Various hands, ‘Tiananmen 1989 — Three Decades Behind China’s Gate of Darkness (June Fourth, 1989-2019)’, China Heritage, 31 May 2019

- Ian Johnson, ‘China’s “Black Week-end” ’, The New York Review of Books, 27 June 2019

- Sophie Beach and Samuel Wade, ‘Remembering June 4th’, China Digital Times, 4 June 2019

- The Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

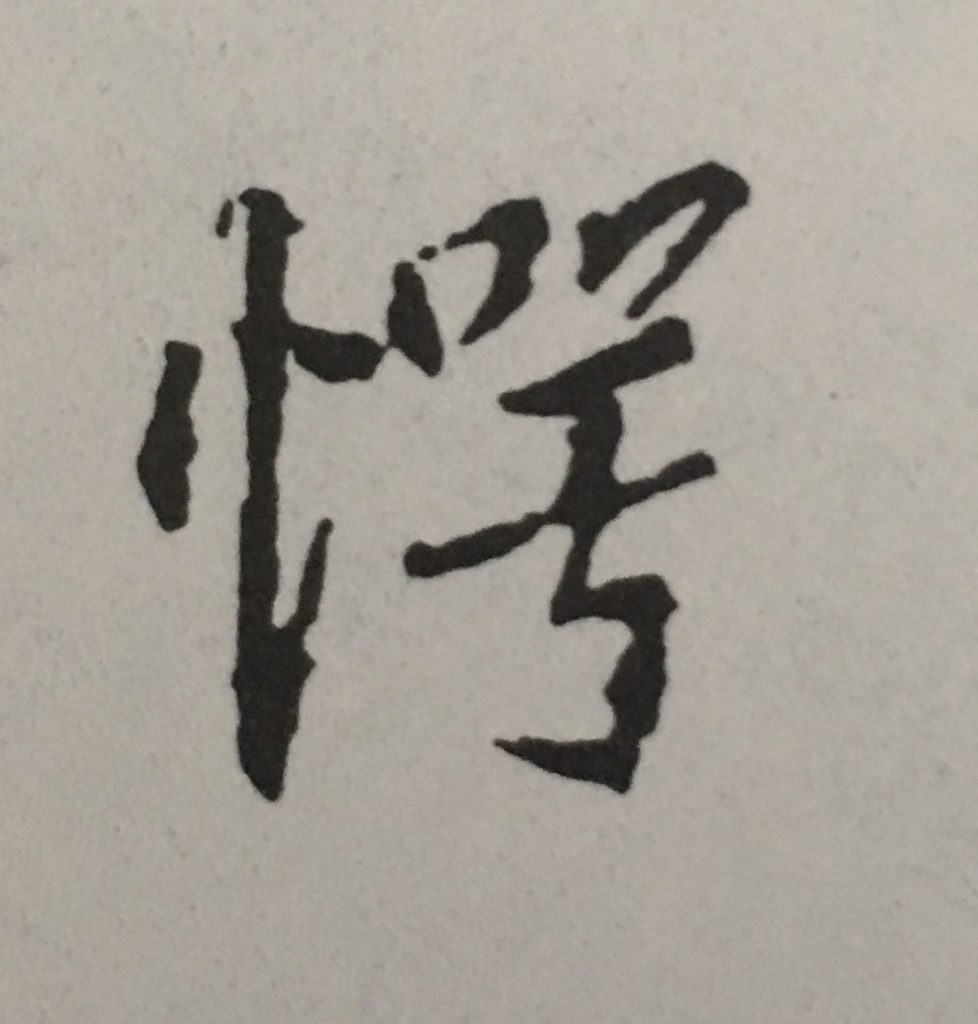

- Note: The word 愕 / 諤 è famously features in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. Simon Leys used the quotation in which it appears as an untranslated epigraph in his 1971 critique of Maoist China, The Chairman’s New Clothes. In 2018, Xu Zhangrun repeatedly employed it in his fearless polemics:

The refusal of one decent man

outweighs the acquiescence of the multitude.

千人之諾諾,不如一士之諤諤。

— Sima Qian, ‘Biography of Lord Shang’

司馬遷, 《史記 · 商君列傳》

***

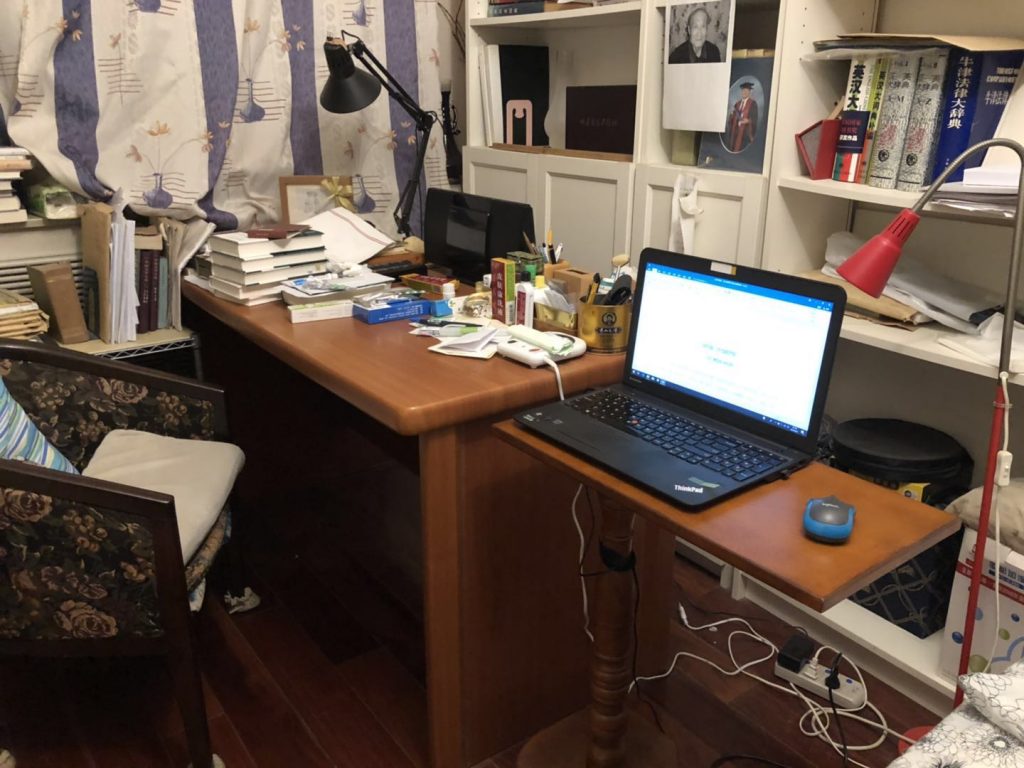

If in a country the size of China

there is no room for a writer’s desk,

I feel I can remain silent no longer

There is a venerable tradition in China of petitioning rulers, and an equally ancient tradition of rulers punishing those who dare petition them. Bi Gan 比干, an argumentative minister of the Shang dynasty (twelfth century BCE), is said to have so infuriated Zhou 紂 that the tyrant, having said, ‘They tell me sages have seven holes in their hearts’, ordered the minister’s chest cut open so he could see for himself. (紂怒曰: 吾聞聖人心有七窍。剖比干觀其心。参見司馬遷《史記 · 殷本紀》)

But appeals to the throne were not always so hazardous. Outside the court, from early days, a drum was placed that could be beaten by petitioners who wanted the court’s attention. The marble huabiao 華表 pillars on either side of Tiananmen Gate were also a reminder to emperors to accept petitions with equanimity.

Petitioning was a major element of the 1989 Protest Movement, a momentous event that is ostentatiously avoided by Official China, but which global China, and the international community, cannot forget. While the Student Movement, or Democracy Movement as it is often called, was generally considered to have begun with the overt student agitation that followed the death of the deposed Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang in April that year, we regard the 1989 Protest Movement as having begun in early January at the initiation of Fang Lizhi 方勵之, the astrophysicist who was purged from the Party for his outspokenness in 1987. He was the first prominent Chinese intellectual to declare publicly that he was carrying on from where Wei Jingsheng 魏京生 left off in 1979. He did so in an open letter addressed to Deng Xiaoping dated 6 January 1989:

Central Military Commission

Communist Party of China,

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It is also the seventieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement. There are sure to be many commemorative activities surrounding these two events. However, people may well be less interested in reflecting on the past than on the present and the future. They hope that these two anniversaries will give them cause for optimism.

In view of this, I would most sincerely suggest that as these anniversaries approach, a nationwide amnesty be declared for all political prisoners, and particularly Wei Jingsheng.

I believe that no matter what opinion one has of Wei Jingsheng, to release him now after he has served some ten years of imprisonment would be a humanitarian gesture that would contribute to a healthy social atmosphere.

This year also happens to be the bicentenary of the French Revolution, and however one views it, the slogans of liberty, equality, fraternity, and human rights have gained universal respect. For these reasons, it is my sincere hope that you will consider my suggestion, thereby earning even greater respect in the future.

Felicitations,

Fang Lizhi

Over the next two months, Fang’s petition inspired a series of similar appeals to the government from writers, scholars, and scientists who had been emboldened by the government’s failure to retaliate against Fang. Later petitioners generally sought safety in numbers. Their appeals were aimed as much at other ordinary Chinese as at the government, for they called for the awakening of conscience, for fairness and justice. They were also cries of desperation, urging people to act before the economic, political, and cultural crises facing China in the late 1980s drove the country to catastrophe.

Some of the petitions originated in Chinese communities in Europe and the United States. In Hong Kong the response was particularly strong: A petition organised in February calling for the release of China’s political prisoners was signed by more than 12,700 people.

The Protest Movement often took on the appearance of a rebellion of the young against the old. The picture the Western media presented was largely one of a movement led by students in their early twenties. Indeed, many of the slogans that appeared during the massive street marches attacked China’s leaders as being too old to govern. Despite the youthful image of the movement, however, the young did not enjoy a monopoly on rebellion.

A number of the masterminds of the movement’s ever-changing strategies were intellectuals in their thirties and forties who generally stayed behind the scenes. And as we read these petitions we also hear the voices of much older people. These include Bing Xin 冰心 and Ba Jin 巴金, writers in their eighties and members of the original May Fourth generation who had called for democracy and freedom in the late 1910s and 1920s, and others like Wang Ruowang 王若望, a Shanghai writer in his seventies who had also been purged from the Party in early 1987. Fang Lizhi himself was in his fifties. In fact, Deng and the other party leaders felt most threatened by the protests of the older generations.

On 28 January, Fang, Wang Ruoshui 王若水 and Su Shaozhi 蘇紹智 were among those present at a salon organised by the independent intellectual journal New Enlightenment 新啟蒙, whose title had been inspired by the May Fourth Movement — also called the ‘Enlightenment Movement’ 啟蒙運動. The gathering was held at the Dule Bookstore 獨樂書屋 in southwest Peking. A number of the guests made statements to the effect that China was facing a crisis of which a central feature was the reappearance of ‘feudalism in the guise of Marxism-Leninism’. Today, during the reign of Xi Jinping three decades later, this expression has an even more powerful resonance.

On 13 February, a petition in support of Fang Lizhi’s letter was organised by the poet Bei Dao 北島 along with Chen Jun 陳軍, an entrepreneur cum political activist. Bei Dao and Chen Jun collected thirty-three signatures for their petition. A number of the signatories were controversial figures in their own right; others, like Bing Xin (born in 1900), were important members of the cultural establishment. The letter was distributed publicly along with Fang’s January petition at a press conference held at Chen Jun’s JJ Café in Peking on 16 February. The JJ Café was used as a venue for the gathering of more signatures for the letter.

On February 22, a spokesperson for the Party judiciary made public an official response to the petition:

Even after this letter was attacked by the authorities in the Chinese media, Bing Xin defended her action by saying that Wei Jingsheng may have been guilty of treason as accused, but it was normal to announce an amnesty on an occasion such as the fortieth anniversary of the state.

After all, she commented to a reporter from an official newspaper, Puyi 溥儀, the last emperor of the Qing dynasty and the puppet ruler of the Japanese state of Manchukuo, was released in the 1950s under just such an amnesty. She hinted that if a traitor like Puyi could be the object of such official magnanimity, so could Wei jingsheng.

On February 26, another petition signed by forty-two intellectuals, mostly scientists, was sent to party and state leaders.

Also on 26 February, Fang Lizhi and his wife, Li Shuxian 李淑嫻, were prevented by Chinese security personnel from attending a Texas-style barbecue hosted by U.S. President Bush at Peking’s Great Wall Sheraton, to which they had been invited by the president. The Chinese authorities, who had vetted the guest list, had not indicated beforehand to either Fang and his wife or the Americans that they would object to Fang’s presence at the banquet. On 27 February, Bei Dao wrote an outraged letter to the government in which he captured a sentiment shared by many people in the Chinese capital at the time.

Last night (26 February) the police physically prevented Professor Fang Lizhi and his wife, Li Shuxian, from attending U.S. President Bush’s farewell banquet at the Great Wall Sheraton Hotel. The actions of the police constitute a gross violation of the human rights of Fang and Li. This incident has deeply shocked me; it is without question a great blot on China’s human rights record.

Professor Fang represents the cream of Chinese intellectuals. The crude infringement of his rights is an insult to every self-respecting Chinese intellectual. If this incident is to be construed as the government’s response to Professor Fang‘s open letter of 6 January and the Petition of Thirty-three, which I initiated on 13 February, then I feel nothing but profound sorrow.

When I initiated that petition I trusted the government would react in a rational and enlightened way. I thought the government would at least listen in a spirit of forbearance to a suggestion made by writers and scholars, especially as our voice was so mild. But if even this cannot be tolerated it shows how fragile democracy and legality are in China. Capitalism has no monopoly on the protection of human rights and freedom of speech; they are the standard of any modern, civilised society.

I believe every Chinese intellectual realises how extremely tortuous China’s path to Reform is. However, during this process, the rulers must become accustomed to hearing different, even discordant, voices. It is beneficial to develop such a habit; it will mark the beginning of China’s progress toward becoming a modern and civilised society.

I am a poet with no interest in politics. Nor do I wish to become an object of media attention. Originally I hoped to withdraw after the publication of our petition, to return once more to my desk, to return to the world of my imagination. Yet if in a country the size of China there is no room for a writer’s desk, I feel I can remain silent no longer.

Bei Dao

Beijing

‘There is no longer enough room for a quiet writing desk in the whole of North China.’ This statement was originally part of the student manifesto of the December Ninth Movement [which called for national unity in the face of the invading Japanese] of 1935. For Bei Dao to paraphrase this declaration shows the level of anger and shock among young people at the repressive attitude of the Communist Party of China regarding the question of human rights.

— Lee Yee 李怡, editor of The Nineties Monthly

(for more by Lee Yee, see The Best China)

On 12 September 1935, student demonstrations led by Communist Party activists at Tsinghua University in Beiping (Beijing) protested against the increasing encroachment of the Japanese Imperial Army in North China. On 13 September, the organisers of the protests published ‘An Appeal Letter to the Nation by Tsinghua University’s Save China Committee’. One line in the appeal — ‘There is no longer enough room for a quiet writing desk in the whole of North China’ 華北之大, 已經安放不得一張平靜的書桌了 — became the slogan both of resistance to the Japanese invaders and of ongoing protest against the supine Nationalist government in Nanking.

***

Shock at Fang’s treatment and growing concern over political and legal rights in China led to an overwhelming response among Hong Kong Chinese, overseas Chinese intellectuals, and China scholars and writers.

Meanwhile, from early March onward, posters attacking the government and supporting Fang Lizhi and calling for demonstrations in support of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ began appearing at Peking University. Since 4 May 1988, concerned intellectuals had met at Peking University in unofficial gatherings called Democracy Salons. On 9 March, such a salon was organised by Wang Dan 王丹, a history student who later became one of the movement’s leaders. The speakers called for action. They included the former 1978-1979 Democracy Wall activist Ren Wanding 任畹定, a dissident and founder of the Chinese Human Rights League who had only recently been released from jail.

In April the government attempted to close down the salon at Peking University.

On 17 March, forty-three important cultural figures in Peking wrote to the Chinese People’s Congress in support of the call for an amnesty for political prisoners. They stressed their belief that such an action would accord with the constitution as well as reflect the popular will.

This letter was initiated by a scholar in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. First on the list of signatories, however, was Dai Qing 戴晴, a prominent journalist, party member, and member of the privileged circle of elite party families. When Dai Qing was later accused of ‘instigating rebellion’ against the party, her involvement with this letter was construed as one of her criminal acts. At the time she defended her action in a telephone interview with the sometime correspondent for The Nineties Monthly in Hong Kong, Zhang Langlang 張郎郎 (who also wrote under just the name Langlang 郎郎):

Langlang: Does the appearance of your petition have anything to do with the upcoming sessions of the National People’s Congress and the Political Consultative Congress?

Dai: Of course; we’re aiming the petition at these meetings.

Langlang: So you are hoping for some concrete results?

Dai: I hold out no such hope. But I think we have to speak up. Now I feel at least I can look myself in the face. What type of person would I be if I didn’t even dare make this type of statement?

***

I do not believe that the Chinese will forever refuse to think for themselves;

I do not believe that the Chinese will never speak out through their writings;

I do not believe that morality and justice will vanish in the face of repression;

I do not believe that in an age in which we are in communication

with the world “freedom of speech” will remain an empty phrase.

— Dai Qing 戴晴, 8 February 1989

— adapted from New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese

Rebel Voices, ed. Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin,

New York: Times Books, 1992, pp.23-29 and p.470

Dai Qing was quoting Bei Dao’s well-know 1976 poem ‘The Answer’ 回答, which included the lines:

Let me tell you, world,

I — do — not — believe!

If a thousand challengers lie beneath your feet,

Count me as number one thousand and one.

我——不——相——信!

縱使你腳下有一千名挑戰者,

那就把我算做第一千零一名。

Some thirty years later, during the protests over the suspension of Xu Zhangrun by Tsinghua University in April 2019, the same lines were referred to, albeit obliquely, by Liu Jianshu 柳建樹 in another powerful poem, ‘They’re Afraid’ 他們怕了:

And that’s why, this spring,

They are fearful again

Fearful of those who believe

For they believe in nothing themselves

Fearful too of those who don’t believe

For they dare to say: I DO NOT BELIEVE!

- For the full poem, in Chinese and English, see ‘They’re Afraid’, China Heritage, 26 April 2019. On 31 May 2019, Dai Qing published her own account of the events of 1989. See 戴晴,《鄧小平在1989》, 香港: 田園書屋。

***

At Home Reading

我家書桌在天地間

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

When I was young I didn’t have a desk for reading or studying. And so any and everything could be my desk, regardless of whether it was the desks in our schoolroom or the table where we ate at home. Lying on a reed mat on the wooden frame of my bed, one leg cocked over the other, I could study while lying on my back: the Heavens above were my desk. Or, sprawled out on my stomach on some flagstones, or maybe on a patch of grass head supported by my hands, I could read just as well: the Earth beneath me was my desk. The words on the page were like a flotilla of sails, their vessels bearing riches from far-flung lands. Those books with worn, dog-eared pages, texts missing passages or lacking whole pages fired my imagination even more. They opened my heart to an expanse more vast than the Heavens, and they let me secretly nestle Heaven and Earth in my heart.

少年讀書,沒有書桌,也無所謂書桌。課桌是書桌,飯桌也是書桌。木床葦席為憑,翹起二郎腿,仰讀,天便是書桌。石板草地撐持,雙手托腮,俯讀,地便是書桌。那鉛字行行,如帆影片片,引領來一個個世界。四角都已翻卷、少字缺頁的紙冊,反倒勾起遐想聯翩,心比天大,天地藏在心中。

In my teens I did have a desk, and it meant a great deal to me. Sitting there I could focus and delve into the innermost thoughts of the writers of today; I could just as well imagine the myriad of concerns of writers past. Ancient sentiments thus mingled in my own thoughts; as my spirit took flight the grinding deprivations of reality were as nought. That desk was a bastion, books like serried ranks of troops; a few inches of space bestowing command over a vast landscape.

‘I Read Therefore I Am’: time is of the essence for it is eternally now. In my mind-travels I encountered beguiling beauties, yet too I experienced stormy nights with my solitary thoughts. My books were a protection and they guarded me from vainglorious pursuits. I also felt the thrill of high aspiration yet would also find myself spent by indulging in lofty self-regard. My desk could usher in such misfortune, too; lives on paper thus speeding past.

青年讀書,有書桌,也很在意書桌。立坐桌前,屏神斂息,傾聽今人心聲,猜詳古人煩惱,將一己之憂思遣送於自家之幽思,神遊冥想中,貧寒云乎哉。以桌為城,擁書作兵,咫尺便是天涯,我讀故我在,時間始自當下。也曾紅袖添香,風雨更闌夜,書桌護我,不叫覓封侯。也曾壯懷激烈,欄幹拍遍,原是書桌造孽,紙上人生。

In middle age you come to understand that books are just that, books, yet they are not merely books, for you realise that the world itself is unfolds around you like a tome; the story of the human heart is just such a volume. You are now aware that books cover your desk, o’erfill the libraries and are found throughout the world. When you leaf through a volume opened in your lap you take delight in it as it responds to being read, no matter how outward fate might unfold like clouds unfurling and roiling above your head.

Whether recumbent or leading against something, eyes exhausted with fatigue, I think that I have only two intimates that truly know my mind: wine and books; people, however, come and go in endless succession. You can never hold on to the ephemeral delights of the season, all you need is a book, for then things that press on the heart and the troubles of the world are whisked away as if on a flowing stream or along with the scudding clouds. Distant travels may be beyond reach, but at one’s desk in the light of the moon you can find yourself in the company of all that was the past. Achievements or losses, concerns and worries, the passage of time, fame and fortune, right and wrong, reading from dusk to dawn, working as a humble teacher, mine is a life that is lived in the embrace of books.

中年讀書,方知書本是書,書本也不是書;始覺世道是書,人心更是書;才懂書桌盛書,書館也盛書,滿天滿地都盛書。膝上翻讀,相對兩悅,管他頭頂雲捲雲舒;臥榻斜倚,醉眼沈眠,知我者,杜康與書也,且由人來人往。留花不住任花飛,有書就好,心事如雲隨流水;天涯路遠無由寄,且置桌上,留待月明探遗编。論得失,憂患大,問枯榮,是非多,但看夕陽接朝陽,做個教書匠,讀書銷平生。

In old age what does reading hold for you? Who am I to say for sure. Confucius already put it well [when asked about death by his disciple Zilu]: ‘You do not yet know life, how could you know death?’ On this planet, life and death are transitory, forever ancient yet ever modern. Everyone gets one chance to experience life, but one’s awareness dawns only gradually. Compared to those who strain for some immediate understanding, it is best to let things take their course, to reveal their lessons over time. The incomparable balm of a book read at night, that one volume in hand, fate within one’s grasp, enlightenment gradually dawning, like the handiwork of nature itself. How can one not be ever thankful?

老年讀書,又將會是何種光景,哪裡知道。夫子說得好,未知生,焉知死。這個星球上,死生來去匆匆,恆舊又恆新,每個人得享一次,只能徐徐知之。如此,與其急急探明,不如留待歲月慢慢教會。書香燈影里,一卷在手,安享定在的宿命,消受漸悟道啓明,豈非天造地設,還不趕快謝天謝地。

Above a heavenly vault o’erstretched with books, below the expansive earth spread with volumes.

A desk to read tucked beneath the skies, a place to write supported by the ground.

I’m delighted that I will always have a desk for reading and writing.

It can always be found; it is everywhere: between those lofty skies and this sustaining earth.

這天,是書;這地,是書。

這天,是書桌;這地,是書桌。

哈,啊,我家書桌在天地間。

— Erewhon Studio

Tsinghua University

26 November 2008

2008年11月26日於無齋

***

***

Source:

-

許章潤, ‘我家書桌在天地間’, , No.1030, 23 January 2019

Still Having His Say

In late October 2018, three months after his controversial polemical magnum opus appeared, Xu Zhangrun published a commentary which was, in part, also a letter addressed to China’s online censorate.

In ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’ 哪有先生不說話?!, Xu cautioned readers about the pitfalls of silence and complicity. Whereas the mechanisms of the state chose to cast the words and warnings of a man of conscience like him into oblivion, they nonetheless give free online license to some of the most heinous figures in post-1949 history, as well as providing liberal access to their writings. The irony is evident; the humour black. With its all-embracing and holistic approach to the media and heart-mind management, Xi Jinping’s China is working with the high-tech present and an Orwellian future to enhance the kind of regime beloved of the country’s autocrats for over two millennia. The author of the following essay points, in particular, to Qin Shihuang (秦始皇, 259-210 BCE), First Emperor of the Qin, the inaugural unified dynasty of China. Excoriated through the ages (even when being emulated), the First Emperor was to find favour with Mao Zedong: for unifying warring kingdoms into a dominant regime, for his rigorous rule of pitiless laws, for his repression of quarrelsome scholars and their contrary views, and for his obsession with standardisation (of weights and measures, transportation and roads, as well as of the written language).

Xu Zhangrun’s reference to the Qin ruler, and his use of quotations and expressions drawn from Sima Qian (司馬遷, d. c.86 BCE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty who chronicled both the achievements and failures of early governance, is hardly accidental. The Party has declared itself, and its Leader, Xi Jinping, to be the nation’s Ultimate Arbiter and Sole Source of Authority 定於一尊, a term that Sima Qian first popularised when describing the autocracy of the Qin emperor. The Qin looms large in other ways as the relentless push by the Communist Party for ever greater unity, standardisation and a politically manipulated ‘rule of law’ resonates with Mao’s obsessions, as well as with the lessons of the Qin and its successor regimes.

Since Mao found much in the rule of the First Emperor of which to approve, it is only fitting that critics of Xi Jinping not only detect the shades of the Great Leader in his inflated self-image (called a new personality cult, or ‘deification movement’ 造神運動), but also note traces in his behaviour of the Qin tyrant and his henchmen. As he wrote this essay in October 2018, Xu Zhangrun daresay had another lesson from the Qin era in mind — the advice of the brilliant and unscrupulous Li Si (李斯, 284-208 BCE), who counselled the First Emperor that, to prevent trouble, he should ‘burn the books and bury the scholars’ 焚書坑儒 (see China Heritage, 22 August 2017).

The title of Xu Zhangrun’s essay — 哪有先生不說話?!, literally, ‘When do teachers not want to speak up?!’ — is a line from a doggerel poem by the famous liberal scholar Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962). He was invited by Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalist government, to a conference at the Cooling (Guling) hill station retreat of Lu Shan in Jiangxi province 江西廬山牯嶺 on the eve of formal war with Japan. The gathering included many other public figures, publishers, opinion makers and thinkers. The topic under discussion was the national crisis confronting the country and Hu made an impassioned speech in which he rejected much of the formulaic folderol of the others. A noted editor and publisher seated next to him dashed off a simple poem in admiration. Hu, famous for having encouraged the use of vernacular Chinese in writing poetry from the time of the literary revolution in 1917 (although the poems he produced were frequently lampooned as artless), immediately responded with an amusing reply (in my translation):

In springtime cats in heat do trill and meow,

While summer cicadas in chorus loudly sing,

All through the night frogs will simply croak,

And teachers, then? They just do their thing!

哪有貓兒不叫春,

哪有蟬兒不鳴夏,

哪有蛤蟆不夜鳴,

哪有先生不說話 ?!

— from Xu Zhangrun, ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’

許章潤, ‘哪有先生不說話?!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018

Nine Essays from the Desk of

Xu Zhangrun, April-June 2019

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘To “Strike Black” Ends Up As “Black Lashing Out” — the kind of illiberal legal system you get when there’s no democracy’ “打黑”渐成“黑打”,没有民主,法制胡可独行?!, 合传媒, 12 April 2019

The absence of legitimate public authority — including that pertaining to the privileges classes — is the greatest threat to Chinese political development today. 包括特殊权力意志在内的公共权力的正当性基础缺失,实在是当下中国政治进程中的心腹大患。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘The Totalitarian Fears both Mind and Soul, Although it Excels at Creating Intellectual Garbage’ 极权政治惧怕大脑拒斥心灵,却擅长制造国家糟粕, 合传媒, 23 May 2019

Under the conditions of the Totalitarian the Humanities are not merely sidelined, they are actively repressed; no, they are reviled and treated with humiliating contempt as part of an attempt to obliterate all serious intellectual work. Through such ideological campaigns as ‘Washing in Public’ [carried out in Chinese universities in the early 1950s], the Anti-Rightist Purge [of 1957], the use of Labour Reform and Re-education Through Labour, the goal was to break the bodies and wound the hearts of scholars of the Humanities. 置身极权体制,就不是“轻忽”文科了,而是压制,不,是轻侮、羞辱直至消灭文科,以及经由包括“洗澡”、“反右”和“劳改”“劳教”在内的一切手段,摧折一切人文学者的身心。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘A Truly Modern China is Only Possible if There is Constitutional Democracy and a Republic for the People’ 惟坐实“立宪民主,人民共和”,方有现代中国, 合传媒, 24 May 2019

The concept ‘Modern China’ denotes a shared place for the hundreds and millions of citizens of this land, a collective way of organising life based on constitutional and democratic norms, creating a community that works on the basis of a legal collectivity. “现代中国”意味着它是亿万公民分享的公共家园,一种立基于立宪民主建制之上的公共建置,一个以法律共同体为基础的公民共同体。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘For an Empire to boast of its glories then the common people must be able to find some ‘pressure value’ [releasing social tensions and allowing them to express themselves]’ 帝国倘有荣光,那是小民尚找得到“解压阀”, 合传媒, 27 May 2019

As the ancients said: the well-being of a land depends not on what its ruling family can accumulate, rather it is reflected in the shared joys and sorrows of its people. To cultivate the self and to contribute positively to those around you, and to give expression to similar uplifting behaviour in all aspects of your life, ‘to support that which is beneficial for people and reject that which is detrimental’, then all groups in society — be they officials in positions of power or commoners pursuing everyday life, all confident that there is a publicly accepted view of right and wrong — only then can everyone sleep soundly at night. 如古人所言,天下之安危,不在一姓之得失,而在万民之忧乐。修己安人,推己及人,“民之所好好之,民之所恶恶之”,则上下之间,官民两头,从违之际,大家都睡得安稳也!

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Be it Training “Famous Judges” or Supporting “Online Red Influencers”, the Law is Nowhere to be Seen’ 从培养“知名法官”到扶持“网红大V”, 法治在哪里, 合传媒, 28 May 2019

There are certain things in the world that unfold according to their very nature; despite the challenge of events, the dramas of life, they cannot be altered by human agency. As for political power, however, people might raise a great hue and cry about ‘focussed training’ [of politically acceptable talents], but it cannot be sustained over time. This is even more so in the case of [officially sanctioned] ‘Online Personages’, for this touches on popular opinion, and no matter how you judge it hidden market forces are constantly at work. 世间事自有轨辙,行云行雨,要死要活,不待人谋。但凡权力操作,“重点培养”,可喧嚣于一时,却难长久,更何况大V 这事涉及人心向背,审丑审美,暗中自有市场规律做主。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Universal Humanity in the Machinery of Totalitarianism, Glimmers of Hope’ 专政机器里的普遍人性,世道酷烈尚有希望如微尘, 合传媒, 29 May 2019

All people — men and women — no matter how different their achievements are also but the children of their parents, and they all share the same range of human emotions and desires as each other. Regardless of nationality they all live under the same skies and they are all living during this portentous era; equally, they all share the same humanity. 人分男女,各秉其能,而皆父精母血的产物,不脱七情六欲。上述诸位,不分国别,天涯咫尺,赶上大时代,幸存七情六欲,而映证的是普遍人性。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘The Law Must have a Soul and Must Cleave to Awareness, Otherwise it is a Mere Tool of Repression’ 法律须有灵魂,秉持正念,否则必成纯粹压迫工具, 合传媒, 31 May 2019

To establish meaningful laws with real ethical value — that is, to formulate a kind of appropriate ‘Mindfulness’ — requires a consensus regarding universally agreed concepts, an understanding of lived human reality, a respect for people’s mores and habits, an appreciation of human nature and support for the importance of maintaining public decency. If, however, the laws of the land are based on aberrant ideas held by people who view all within their power as merely the ‘Family Enterprise’ of their particular Party or Faction, then will be merely formalistic and soulless. 善法得立,在于秉持普世理念,体恤凡尘生计,切合民情风尚,不违人性,而一以护持公义为最高准绳,堪为正念。恶法既成,正因为邪念当道,居然视天下为一党一派之家业,没了灵魂。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘It is Folly to Believe that Everyone Can be Silenced — ‘Teachers Just Keep Doing Their Thing’ Regardless’ 欲令天下无声,何其愚妄,“哪有先生不说话?!”, 合传媒, 3 June 2019

Only when others can hear what people want to say is its possible to have a dialogue, let alone a conversation. And it is through just such exchanges that we rise from our solipsism in the spirit of shared community, affirming thereby our humanity. Moreover, it is only in such a collectivity of spirit, and indeed only in such a community of communication, that we can truly enjoy freedom. 说话就得让人听见,才能构成对话与交谈,让我们摆脱孤立的私性状态,获得公共存在,保持人性。进而,我们的公共存在状态,也唯有这种公共存在状态,才赋予我们以自由。

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘The “WeChat Moment” — we don’t believe the sky will fall in despite all attempts to silence us’ “微信时刻”,我们确信世界不会因为钳口就崩塌, 合传媒, 4 June 2019

Discussion and conversation — private acts that constitute mini communities — can give expression to the soul and affirm one’s individual humanity. They are the baseline too of what will be a dogged survival through these Dark Times. If we didn’t have those ‘all-night discussions around the kitchen table’ protecting against the relentless winds and bitter temperatures, how could we ever survive until the springtime when flowers blossom once more? 交谈,正是交谈,一种私性领域里的个体公共形式,唤醒了心灵,维持住了人性,支撑起了让我们熬过漫漫长夜的基本底线。若无厨房里的彻夜交谈,为我们挡风御寒,怎能撑到春暖花开!

***